Melanoma is one of the less common types of skin cancer, but it accounts for the majority of the skin cancer deaths (about 75 percent).

The five-year survival rate for early stage melanoma is very high (98 percent), but the rate drops precipitously if the cancer is detected late or there is recurrence.

So a great deal rides on the accuracy of the initial surgery, where the goal is to remove as little tissue as possible while obtaining “clean margins” all around the tumor.

So far no imaging technique has been up to the task of resolving the melanoma accurately enough to guide surgery.

Instead surgeons tend to cut well beyond the visible margins of the lesion in order to be certain they remove all the malignant tissue.

Two scientists at Washington University in St. Louis have developed technologies that together promise to solve this difficult problem.

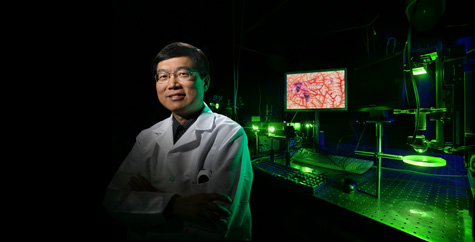

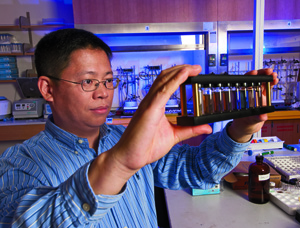

Their solution, described in the July issue of ACS Nano, combines an imaging technique developed by Lihong Wang, PhD, the Gene K. Beare Distinguished Professor of Biomedical Engineering, and a contrast agent developed by Younan Xia, PhD, the James M. McKelvey Professor of Biomedical Engineering.

Together, the imaging technique and contrast agent produce images of startling 3-dimensional clarity.

Photoacoustic tomography

The imaging technique is based on the photoacoustic effect, discovered by Alexander Graham Bell 100 years ago. Bell exploited the effect in what he considered his greatest invention ever, the photophone, which converted sound to light, transmitted the light, and then converted it back to sound at the receiver.

(The public preferred the telephone to the photophone — by some facetious accounts — because they just didn’t believe wireless transmission was really possible.)

In Bell’s effect, the absorption of light heats a material slightly, typically by a matter of millikelvins, and the temperature rise causes thermoelastic expansion.

“Much the same thing happens,” Wang says, “when you heat a balloon and it expands.”

If the light is pulsed at the right frequency, the material will expand and contract, generating a sound wave.

“We detect the sound signal outside the tissue, and from there on it’s a mathematical problem,” Wang says. “We use a computer to reconstruct an image.

“We’re essentially listening to a structure instead of looking at it,” Wang says.

“Using pure optical imaging, it is hard to look deep into tissues because light is absorbed and scattered,” Wang says. “The useful photons run out of juice within one millimeter.”

Photoacoustic tomography (PAT) can detect deep structures that strongly absorb light because sound scatters much less than light in tissue.

“PAT improves tissue transparency by two to three orders of magnitude,” Wang says.

Moreover, it’s a lot safer than other means of deep imaging. It uses photons whose energy is only a couple of electron-volts, whereas X-rays have energies in the thousands of electron-volts. Positron emission tomography (PET) also requires high-energy photons, Wang says.

A smart contrast agent

Photoacoustic images of biological tissue can be made without the use of contrast agents, particularly if tissues are pigmented by molecules like hemoglobin or melanin.

Still, photoacoustic images of melanomas are fuzzy and vague around the edges. To improve the contrast between the malignant and normal tissue, Xia loads the malignant tissue with gold.

“Gold is much better at scattering and absorbing light than biological materials,” Xia says. “One gold nanocage absorbs as much light as a million melanin molecules.”

Xia’s contrast agent consists of hollow gold cages, so tiny they can only be seen through the color they collectively lend to the liquid in which they float.

By altering the size and geometry of the particles, they can be tuned to absorb or scatter light over a wide range of wavelengths.

In this way, the nanoparticles behave quite differently than bulk gold.

For photoacoustic imaging, Xia’s team tunes the nanocages to absorb strongly at 780 nanometers, a wavelength that falls within a narrow window of tissue transparency in the near-infrared.

Light in this sweet spot can penetrate as deep as several inches in the body.

Once injected, the gold particles naturally tend to accumulate in tumors because the cells that line a tumor’s blood vessels are disorganized and leaky.

But Xia has dramatically increased the uptake rate by decorating the nanoparticles with a hormone that binds to hormone receptors on the melanoma’s cells.

The molecule is alpha-melanocyte-stimulating hormone, slightly altered to make it more stable in the body. This hormone normally stimulates the production and release of the brown pigment melanin in the skin and hair.

As is true in many types of cancers, this hormone seems to stimulate the growth of cancerous cells, which produce more hormone receptors than normal cells.

In experiments with mice, melanomas took up four times as many “functionalized” nanocages than nanocages coated with an inert chemical. With the contrast agent, the photoacoustic signal from the melanoma was 36 percent stronger.

But seeing is believing. Subcutaneous mouse melanomas barely visible to the unaided eye show up clearly in the photoacoustic images, their subterranean peninsulas and islands of malignancy starkly revealed.