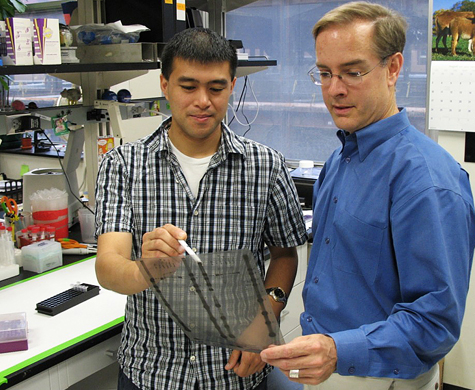

Robert Boston

Barry Sleckman (right), MD, PhD, and Eric Gapud, a student in the Medical Scientist Training Program, examine the results of an experiment looking at the generation of chromosomal translocations, or instances where broken DNA strands have been erroneously reconnected. Sleckman’s research focuses on creation and repair of DNA breaks, a topic that is important for understanding cancer and immunological and developmental disorders.

Barry Sleckman, MD, PhD, was a busy young entrepreneur and disaffected commuter college student when his life began taking a sudden series of unexpected turns in the late 1970s.

One weekend, a close friend seeking a job with the state police urged Sleckman, now the Conan Professor and director of Laboratory and Genomic Medicine at Washington University School of Medicine, to come to the civil service exam with him to boost his morale and ease his worries. Sleckman agreed to do it, but when they arrived at the exam, Sleckman found out the only way he could go in was if he took the exam, too.

“I passed the test, the medical and physical fitness exams, the psychiatric and background checks, and, three months later, they called me back and said, ‘Congratulations, you’re a member of the 95th New Jersey State Police Academy,’” he says.

Sleckman took a look at the golf-club repair business he founded at age 12 and ran from his parents’ basement (with three employees) and at the busy work in college that kept cluttering up his schedule and decided that perhaps destiny was calling.

He knew he was mistaken before a year had passed. But his eight-month stint in the state police left him fascinated by the medical work he’d seen paramedics perform and wondering if he could become a doctor.

Catch-up work was required. Preoccupied with his business, he had let his high school grade-point average slip into “one-point-something” territory. Despite graduating in the bottom quarter of his high school class, Sleckman eventually earned a medical degree and a doctorate at Harvard University.

Gene Oltz, PhD, professor of pathology and immunology and a friend of Sleckman’s since they met as postdoctoral researchers, sees this pattern continuing.

“One of the things that makes Barry an extraordinary scientist is that he fearlessly goes where his instincts tell him he should be going,” Oltz says. “There are many scientists who get a hint of something interesting in another direction, but there are activation barriers that make them shy away, such as new equipment to buy or new techniques to learn. That’s just not the case with Barry.”

Finding the ‘fascinating stuff’

Sleckman was born in Bermuda in 1960. His father and mother met in Iran, where his father was an accountant computerizing financial records for Esso (known as ExxonMobil in the United States), and his mother worked in the U.S. Embassy.

“Dad had been doing that for Esso around the world, but when he married my mother, he told Esso he needed a permanent posting, and they assigned him to Bermuda,” he says.

Bermuda might seem like an intriguing place to live, but the Sleckmans found the lack of variety on the island too constricting, so they moved to New Jersey when Sleckman was 6 years old. He hasn’t been back to Bermuda since.

At Harvard, an immunology class with Emil Unanue, MD, now the Paul and Ellen Lacy Professor of Pathology and Immunology at Washington University School of Medicine, committed him to the study of immunology.

“Emil, Andrey Shaw (MD) and I teach this course now, and we’ve talked about what it is in a particular class that gets students to commit to a subject,” Sleckman says. “Emil was clearly excited about immunology, and he conveyed that to the class in a way that inspired me to realize that I was not alone in finding this stuff fascinating.”

As he went through the process of seeking his first faculty appointment during the 1997-98 academic year, Sleckman didn’t inquire at WUSTL until March, when a mentor prompted him to do so. He soon was exploring job possibilities with Unanue, his former teacher.

“I have a colleague who describes it as ‘the land-speed record’ for taking a job,” Sleckman says, laughing. “It was clearly just such a great immunology environment here at Washington University.”

Fixing rips in the genetic code

Sleckman’s current research focus is the risky business of repairing breaks in DNA.

“This is actually something that happens regularly as a part of normal biological processes,” Sleckman says. “For example, during an hour in an average middle-aged human, immune cells known as lymphocytes will make and repair 66 million breaks in their own DNA.”

Immunologists showed decades ago that the breaks allow lymphocytes to splice together their genetic materials in new ways that help the immune system recognize and fight invaders. But if just one in 20 million breaks isn’t spliced together properly and the cell with the error fails to self-destruct, cancer can result.

Courtesy photo

The Sleckman family: (from left) Barry; son, Christopher, 14; wife, Bethany; and daughter, Katherine, 11.

Sleckman’s lab was the first to demonstrate that self-induced DNA breaks also can serve as signals that activate genes unrelated to DNA repair but important for normal cell function and development. In a 2008 paper published in Nature, he found that DNA breaks in lymphocytes activated genes that cause lymphocytes to travel from where they’re made in the bone marrow to where they’re needed to fight infection. His lab now is following up on this idea in macrophages, another important class of immune cells.

Sleckman also has produced surprising evidence that the best way to fix a DNA break may depend upon the phase of the cell life cycle a cell is in when its DNA breaks.

“When these processes are misaligned — a DNA repair process for one phase of the cell cycle is applied when the cell is at a different stage in that cycle — you can get aberrant joinings of the broken ends of the DNA, and that’s dangerous,” Sleckman says.

Herbert “Skip” Virgin IV, MD, PhD, the Edward R. Mallinckrodt Professor and head of Pathology and Immunology, credits Sleckman with “major contributions to our understandings of cancer and immunology.”

“He’s just a terrific, outstanding scientist, teacher and mentor who does everything with grace, enthusiasm and a constructive attitude,” Virgin says.

Enjoying ‘social science’

Sleckman’s office has no windows, so he decided to flood the room with what he calls his own “windows”: memorabilia such as the sign from his golf club repair business; bottles of celebratory champagne from his thesis defense and from other significant events, each labeled with the date and the occasion; posters from marathons he has run; and dozens of pictures.

By far the dominant subjects of the pictures in his office are people: lab members, students and colleagues at meetings, parties and events.

“Barry loves the social aspects of science and teaching,” Oltz says. “His Thanksgiving turkey fries and semiannual pig roasts are legendary in the department.”

Third-year medical student Evan Graboyes has been to St. Louis Blues games with Sleckman and his family and enjoys Sleckman’s annual Super Bowl party for the medical students.

“He truly cares about the students, both as medical doctors in training and as human beings with interests and hobbies outside of medicine,” Grayboyes says.

Sleckman is renowned as an outstanding instructor. Medical students have elected him Professor of the Year six times in the past decade. He has won the Distinguished Service Teaching Award twice, won the Stanley Lang Lecturer of the Year Award in 2002 and received the Samuel R. Goldstein Leadership Award in Medical Education in 2009.

“It’s important when you teach at a medical school to try to convey the critical points and concepts instead of the large amounts of detail that aren’t destined to have a very long half-life in students’ brains, anyway,” he says.

Sleckman jokes that he teaches medical school immunology for English majors, not biology majors.

“The important thing is to start simple,” he says. “Among 100 students, there will be 15-20 who will be bored as a result, but there will also be 15-20 who are lost, and about 60 for whom the porridge is just right.

“I always wonder if we’re starting things off too simple, but year after year on the exit exams, Washington University students always score very high on the immunology questions.”

Fast facts about Barry Sleckman

Family: Wife, Bethany, MD, an oncologist at St. John’s Mercy in Creve Coeur, Mo.; son, Christopher, 14; daughter, Katherine, 11

Marathons completed: Four — two New York marathons and two Boston marathons

Peaks climbed: Mt. McKinley (also known as Denali) in Alaska; Mt. Rainier, Mt. Baker, Glacier Peak and Mt. Shuksan in Washington; and Gannett Peak in Wyoming

Hobbies: Biking and “cooking escapades”

Shares season tickets for: The St. Louis Blues, the St. Louis Rams and the St. Louis Cardinals

Favorite places to eat include: Wasabi in Clayton, Mo.

Best advice for medical school teachers: “Try not to be out of touch with how little you actually knew as a first-year medical student.”