Audio download available

Most people at risk for developing glaucoma due to high eye pressure do not need treatment, according to a large, multicenter study.

The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study (OHTS) investigators, led by researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, report in the Archives of Ophthalmology that most patients with high eye pressure but no glaucoma damage can be carefully monitored rather than given eye drops.

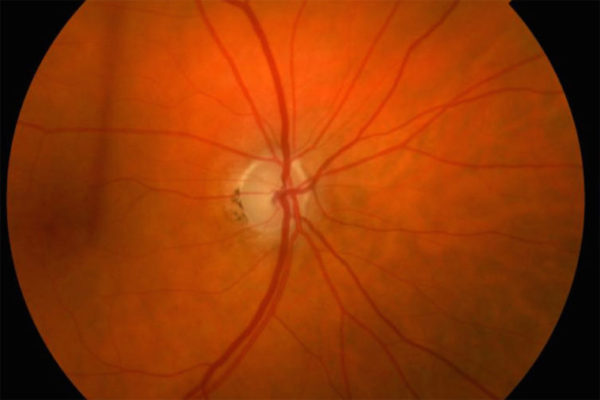

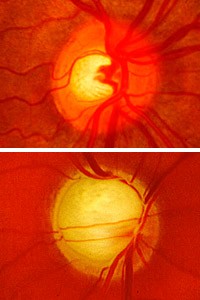

The researchers say many patients at highest risk of developing glaucoma, such as those who have elevated pressure along with other symptoms — such as thin corneas or large cup/disc ratio (a measure of the part of the optic nerve visible inside the eye) — should be treated with pressure-lowering drops, but those without the additional symptoms probably don’t need the therapy.

“It’s clear that people with high eye pressure and high risk of developing glaucoma do benefit from early medical treatment,” says Michael A. Kass, M.D., lead investigator of the OHTS study. “But we have learned that not everyone with high pressure is at high risk.”

The OHTS study ran from 1994-2009. For the first seven years, half of the 1,636 subjects with elevated pressure, ages 40 to 80, received eye drops. The other half were closely monitored but received no medication. That first phase of the study determined that drops could reduce development of the potentially blinding disease by more than 50 percent.

After the first phase of the study, OHTS researchers put everyone on eye drops, and now they have determined that in patients at lower risk, there wasn’t much difference between those who started using eye drops in 1994 and the original control group, who didn’t get drops until more than seven years later.

Among those with high pressure but otherwise at low risk, 7 percent in the early treatment group developed glaucoma, compared with 8 percent in the delayed treatment group who developed the disease.

By contrast, 28 percent of high-risk patients in the original treatment group went on to develop glaucoma, compared with 40 percent of the high-risk patients in the delayed treatment group. Fortunately, most people with modest elevations in eye pressure fall into the low-risk group.

“This study has determined that close monitoring is an appropriate option for large numbers of people with ocular hypertension but no damage from glaucoma,” says Paul A. Sieving, M.D., Ph.D., director of the National Eye Institute of the National Institutes of Health, which funded the OHTS study. “This is a strong example of research that can result in more appropriate treatment at a lower cost.”

Elevated eye pressure is an important glaucoma risk factor, but it isn’t the only one. A few years ago, Kass, the Bernard Becker Professor and head of the Department of Ophthalmology and Visual Sciences at Washington University, and Mae O. Gordon, Ph.D., professor of ophthalmology and visual sciences and of biostatistics, developed a model to quickly assess glaucoma risk in individual patients.

The model relies on five key risk factors: a patient’s age, pressure in the eye, cup/disc ratio, corneal thickness and pattern standard deviation (a measurement derived from computerized visual field tests).

“When we consider these five risk factors and assign statistical values, it’s possible to determine an individual’s risk of developing glaucoma during the next five years,” Gordon says.

African-Americans as a group appear to have thinner corneas and a slightly different anatomical structure to the optic nerve than people from other ethnic backgrounds. Kass says because of the elevated risk, close monitoring may not be appropriate for many African-American patients. He says individual risk assessments should determine which patients receive treatment and which patients are followed.

“Glaucoma is about four times more common in African-Americans than in people of European ancestry, and blindness from glaucoma is about six times more common in African-Americans,” Kass says. “Treatment does help, but we know from our study that even when treatment is identical, the risk for African-Americans remains significantly greater.”

During the initial phase of the OHTS study, only 4.4 percent of Caucasian patients using drops developed glaucoma, compared with 8.4 percent of African-American patients and 16.1 percent of the African-Americans not receiving drops.

“In low-risk patients, close observation looks to be an effective approach,” Kass says. “But it’s important that all patients receive regular eye exams, to detect elevated pressure and to assess other risk factors for glaucoma. And if an individual has high eye pressure and no glaucoma damage, you should speak to your eye doctor about your risk for developing glaucoma and whether you might benefit from preventative treatment.”

Primary open-angle glaucoma:

Primary open-angle glaucoma affects about 2.2 million Americans age 40 and over. Half are not aware they have the disease. Vision loss from glaucoma occurs when the optic nerve is damaged. In most cases, elevated eye pressure, also called ocular hypertension, contributes to this damage. This causes gradual loss of peripheral (side) vision.

As the disease progresses, the field of vision gradually narrows, and blindness can result. Glaucoma has no early symptoms, and by the time people experience problems with their vision, many have a significant amount of optic nerve damage. However, if detected early, glaucoma usually can be controlled and serious vision loss prevented. Comprehensive dilated eye examinations are recommended at least once every two years for African-Americans over age 40 and for all people over age 60.

The Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study was sponsored by the National Eye Institute (NEI) and the National Center on Minority Health and Health Disparities (NCMHD) of the National Institutes of Health (NIH). The study also was supported by Research to Prevent Blindness and Merck Research Laboratories.

Kass MA, Gordon MO, et al. for the Ocular Hypertension Treatment Study Group. Delaying Treatment of Ocular Hypertension. Archives of Ophthalmology, vol. 128 (3); pp. 276-287

Washington University School of Medicine’s 2,100 employed and volunteer faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals. The School of Medicine is one of the leading medical research, teaching and patient care institutions in the nation, currently ranked third in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.