Bacteria that cause urinary tract infections (UTIs) make more tools for stealing from their host than friendly versions of the same bacteria found in the gut, researchers at the School of Medicine and the University of Washington have found.

Henderson

Henderson

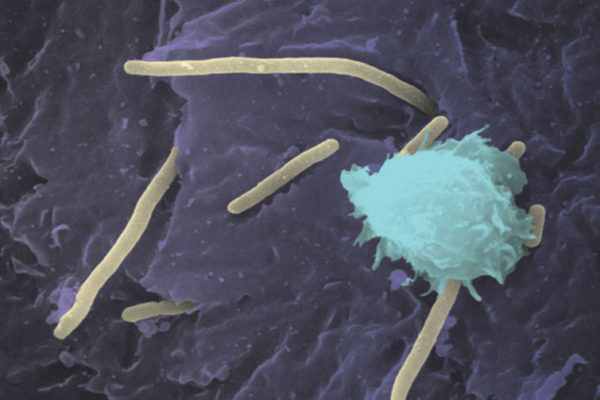

The tools, compounds called siderophores, allow the bad bacteria to steal iron from their hosts, making it easier for the bacteria to survive and reproduce. But they also provide a potential way to target the bad strains of bacteria for eradication without adversely affecting the good strains, researchers report in a study published online Feb. 20 by PLoS Pathogens.

“When we treat an infection with antibiotics, it’s like dropping a bomb — nearly everything gets wiped out, whether it’s helpful or harmful,” said lead author Jeff Henderson, M.D., Ph.D., instructor in medicine. “We’d like to find ways to target the bad bacteria and leave the good bacteria alone, and these siderophores are a great lead in that direction.”

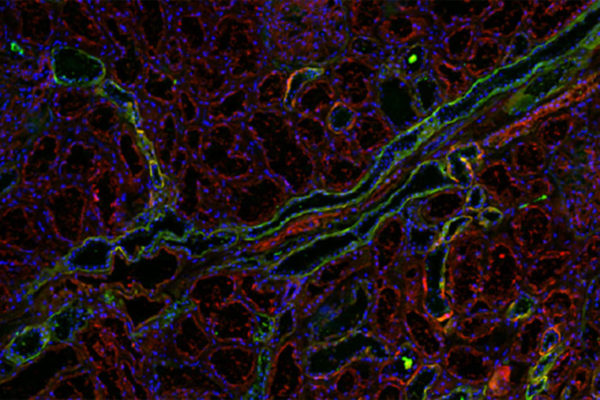

UTIs are one of the most common infections, causing around $1.6 billion in medical expenses every year in the United States. Half of all women will experience a UTI at some point in their lives, and recurrent UTIs affect 20 percent to 40 percent of these patients. Scientists say 90 percent of all UTIs are caused by the bacterium Escherichia coli (E. coli).

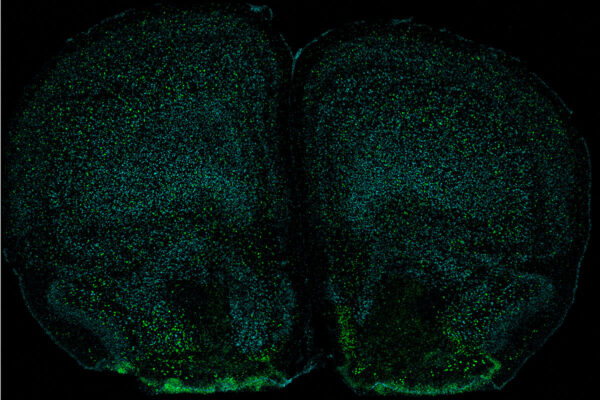

The E. coli that causes UTIs may come from the human gut, where several strains of the bacteria reside. Scientists think some of those strains help their human hosts by aiding digestion and blocking other infectious organisms. To study how friendly and infection-causing E. coli strains differ, Henderson and colleagues at the Center for Women’s Infectious Disease Research at WUSTL used a new approach called metabolomics, which analyzes all the chemicals produced by a cell, including bacterial growth signals, toxins and waste products.

“This allows us to look at the end products of many genes working together,” said senior author Scott Hultgren, Ph.D., the Helen L. Stoever Professor of Molecular Microbiology. “We assess what all the various assembly lines are producing and which products disease-causing bacteria prefer to make, such as certain siderophores.”

E. coli bacteria studied in the experiment came from stool and urine samples from recurrent UTI patients treated at the University of Washington. Researchers found that the strains from urine made more of two siderophores that help bacteria scavenge for iron to support their own survival.

There may be multiple ways to take advantage of the infectious bacterial strains’ reliance on siderophores. Researchers will try to block or disrupt the activity of the proteins that make siderophores, but they also may use what Henderson calls a “Trojan horse” strategy.

“To steal iron, siderophores have to be sent out from the cell, bind to the iron and then be taken back into the cell,” he said. “If we can design an antibiotic that looks like a siderophore, we might be able to trick only disease-causing bacteria into taking up the drug while leaving other bacteria alone.”