Researchers seeking ways to defeat malaria have found a way to get help from the parasite that causes the disease.

Scientists at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis stepped aside and let Plasmodium falciparum, one of the deadliest strains of malaria, do a significant portion of the genetic engineering work in their new study. With that help, they could unambiguously show that the parasite relies heavily on a one-of-a-kind protein that it only makes in small quantities, two qualities that make the protein an attractive drug development target.

“The protein in question, which we’re calling Pcalp, belongs to a class of cutting proteins known as proteases, which also are good drug targets generally,” says senior author Daniel E. Goldberg, M.D., Ph.D. “There’s already quite a bit of knowledge available about how we can inhibit such proteins, spurred in part by the effort to develop drugs to combat HIV.”

The study is published online in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

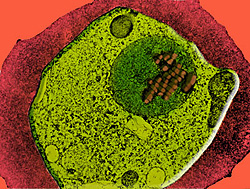

Pcalp caught researchers’ attention because it’s the parasite’s only calpain, a specialized form of protease. Humans, in contrast, have more than a dozen calpains. Because the parasite makes so little Pcalp during the stage of its lifecycle that takes place in human blood, lead author Ilaria Russo, Ph.D., a postdoctoral fellow, had to develop special techniques just to detect it.

“When we first talked about Pcalp, the low levels we reported had people skeptical that it could do much at all during human infection,” Goldberg says. “They suggested that Pcalp had to be more important to malaria during other stages in its lifecycle, such as the one that takes place in mosquitoes.”

Normally microbiologists test a protein’s importance by simply removing the gene for the protein and checking if the organism survives. However, a few recent reports suggested that the way scientists were removing genetic material from the parasite could adversely impact its chances for survival, producing false positives—genes that seemed to be essential but were not.

To solve this problem, Russo took advantage of microorganisms’ natural ability to genetically re-engineer themselves using mobile bits of DNA called plasmids. She created multiple copies of two plasmids: one with a slightly altered but still functional version of Pcalp, and another with a copy of Pcalp mutated so that it could not work correctly.

The parasite could incorporate the first version of Pcalp, but the researchers found evidence that it avoided stitching the second, defective version into its DNA. This showed that Pcalp is essential to the malaria parasite, according to Goldberg.

When Russo adapted a system previously only used in higher organisms to let her increase or decrease levels of Pcalp available to the parasite, she found evidence that it needs the Pcalp protein to progress through its normal cell cycle.

“There are a number of other labs already interested in developing a drug to block Pcalp, and in the meantime we’re going to try to further clarify exactly how Pcalp helps regulate the parasite’s cell cycle,” Goldberg says.

Russo I, Oksman A, Vaupel B, Goldberg DE. A calpain unique to alveolates is essential in Plasmodium falciparum and its knockdown reveals an involvement in pre-S-phase development. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, online edition.

Funding from the National Institutes of Health supported this research.

Washington University School of Medicine’s 2,100 employed and volunteer faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals. The School of Medicine is one of the leading medical research, teaching and patient care institutions in the nation, currently ranked fourth in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.