Information obtained from a new application of photoacoustic tomography (PAT) is worth its weight in gold to breast cancer patients.

For the first time, Lihong Wang, Ph.D., the Gene K. Beare Distinguished Professor of Biomedical Engineering, and Younan Xia, Ph.D., the James M. McKelvey Professor in the Department of Biomedical Engineering, have used gold nanocages to map sentinel lymph nodes (SLN) in a rat noninvasively using PAT technology.

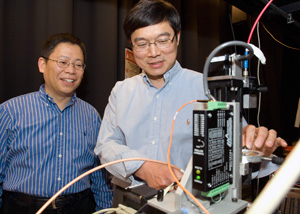

David Kilper/WUSTL Photo

Younan Xia Ph.D. (left), the James M. McKelvey Professor in the Department of Biomedical Engineering, and Lihong Wang, Ph.D., the Gene K. Beare Distinguished Professor of Biomedical Engineering, examine the photoacoustic tomography machine in Wang’s Whitaker Hall laboratory.

Wang’s lab, the largest PAT lab in the world, is credited with the invention of super-depth photo-acoustic microscopy, and Xia’s lab invented the gold nanocages.

Their work, supported by the National Institutes of Health, can minimize invasive surgical lymph node biopsy procedures to determine if breast cancer has metastasized and reduce the patient’s exposure to radioactivity. The nanocages also have the potential to serve as an alternative to chemotherapy and kill targeted cancers by heating them up. The research was published in a recent online issue of Nanoletters.

PAT blends optical and ultrasonic imaging to give high-resolution images of the body that contain information about physiology or tissue function. Molecules already present in the body (endogenous molecules), such as melanin, hemoglobin or lipids, can be used as endogenous contrast agents for imaging. When light is shone on the tissue, the contrast agent absorbs the light, converts it to heat and expands. This expansion is detected as sound and decoded into an image.

“Using pure optical imaging, it is hard to look deep into tissues at high resolution because light scatters,” Wang said. “The useful photons run out of juice within one millimeter. PAT improves tissue transparency by two to three orders of magnitude because sound scatters less than light. This allows us to see through the tissue by listening to the sound.”

Exogenous contrast agents (those found outside the body) like the gold nanocages developed by Xia’s group can be used to image parts of the body that even contain endogenous contrast agents. These nanocages are especially attractive because their properties can be tuned to give optimal contrast, and gold is non-toxic.

“By controlling the synthesis, we can move the absorption peak for the nanocages to a region that allows them to be imaged deep in tissue,” Xia said. “We can also attach biomolecules to the surface of the nanocages so they are targeted to cancer cells.”

The SLN, the first draining node, is often biopsied in breast cancer patients to determine if the cancer has metastasized.

“To find the SLN, doctors inject radioactive particles and a blue dye into the breast,” Wang said. “The lymphatic system gobbles up the injected material, treating it as foreign matter and accumulating it in the SLN.

“The radioactive particles can be detected using a Geiger counter held to the breast to locate the lymph nodes. Then, the doctors surgically open the breast, follow the blue dye and dissect the SLN,” Wang said.

Wang and Xia’s technique allows the SLN to be imaged safely without radioactivity or surgery. A piece of tissue can then be removed using a minimally invasive needle biopsy and tested for cancer.

“We will convert an invasive surgical procedure into a minimally invasive needle biopsy,” Wang said.

In the future, the researchers hope to attach molecules to the surface of the gold nanocages that will selectively bind to cancer cells, making a “smart contrast agent.”

Then, the nanocages will only be detected where cancer is present, eliminating the need for a needle biopsy.