Neoclassical sculptor Harriet Goodhue Hosmer (1830-1908) was one of the most successful female artists of her day, described by poet Elizabeth Barrett Browning as “a perfectly emancipated female.” She also was the first woman to study anatomy at what would become the School of Medicine and produced many of her most significant works — such as the bronze statue of Missouri Senator Thomas Hart Benton in Lafayette Park — for St. Louis patrons.

Beginning Friday, May 2, and continuing through July 21, the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum will join other local institutions in celebrating Hosmer’s life and work. Four sculptures, drawn from the permanent collections of the Kemper museum and the Saint Louis Art Museum, will be on view in Kemper’s Teaching Gallery.

In addition, the museum will host an international symposium organized by the Lafayette Park Conservancy on “The Life and Works of Harriet Goodhue Hosmer” June 14.

Other events will include “Celebrating Harriet Hosmer,” a discovery tour presented by the Missouri History Museum May 4; the “Hats Off to Hattie Gala,” a fundraiser for the restoration of the Benton monument, sponsored by the Lafayette Park Conservancy June 14; and a gallery talk at the Kemper Art Museum by Erin Sutherland, a doctoral candidate in the Department of Art History & Archaeology in Arts & Sciences June 18.

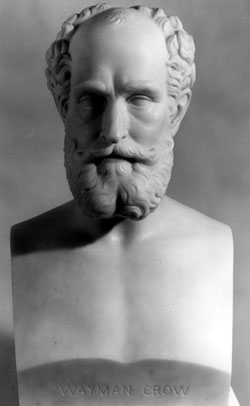

Born in Watertown, Mass., Hosmer attended Mrs. Charles Sedgwick’s Young Ladies’ School in Lenox, Mass., where she met Cornelia Crow, daughter of Wayman Crow, a prominent St. Louis merchant. (In 1853, Wayman Crow, then a Missouri state senator, secured the charter for the institution that would become Washington University.) After graduating, Hosmer studied briefly with Boston sculptor Peter Stephenson but was soon frustrated by her inability to study anatomy, since she was excluded from all-male medical classes.

In 1850, Hosmer traveled to St. Louis, where she lived with the Crow family and earned a certificate in anatomy from the Missouri Medical College, a predecessor to the School of Medicine.

In 1852, she decamped to Rome, where she trained with prominent English sculptor John Gibson and honed her skills by copying masterworks. Hosmer also befriended a number of prominent artists and writers, notably Browning and Nathaniel Hawthorne — she was a model for Hilda in Hawthorne’s novel “The Marble Faun” (1860) — and joined a group of expatriate women artists dubbed “The White Marmorean Flock” by Henry James.

The exhibition will feature two important early marbles based on classical myth, both part of the Kemper Art Museum’s permanent collection. “Daphne” (1854) — Hosmer’s first original work in Rome, which she gave to the Crow family — depicts the beautiful daughter of the river god Peneus, who, fleeing the god Apollo, is transformed into a laurel tree. “Oenone” (1854-55), Hosmer’s first large-scale figural work, was commissioned by Wayman Crow and depicts the mythological wife of Paris, whom he abandoned in favor of Helen.

Though highly idealized, both works are notable for their sense of emotional restraint. Daphne is calm and composed — her gaze tranquil and her hair neatly tied — even at the moment of her transformation. Oenone, shown kneeling over a rustic shepherds’ crook, is similarly serene and introspective. Indeed, it is unclear whether Hosmer has depicted Oenone mourning Paris’ desertion or contemplating her own subsequent refusal to help him after the fall of Troy.

Also on view will be “Portrait of Wayman Crow, Sr.,” a marble bust created in 1866 and presented to Wayman Crow soon after at a University commencement ceremony, and “Hands of Robert and Elizabeth Barrett Browning” (1853), a small bronze from the collection of the Saint Louis Art Museum.

The Hosmer exhibit opens with a reception at 7 p.m. Friday, May 2, in the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum’s Teaching Gallery. Both the reception and the exhibition are free and open to the public. For more information, visit kemperartmuseum.wustl.edu.