Layers on Mars are yielding history lessons revealed by instruments flying overhead and rolling across the surface.

That’s the message being presented today by NASA researchers, including two from Washington University in St. Louis, at a meeting of the American Geophysical Union in San Francisco.

Roger Phillips, professor of earth and planetary sciences in Arts & Sciences and director of the McDonnell Center for Space Sciences, is deputy team leader of the Shallow Subsurface Radar instrument on the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, NASA’s newest Mars spacecraft.

Raymond E. Arvidson, the James S. McDonnell Distinguished University Professor and chair of earth and planetary sciences, is deputy principal investigator for the NASA Mars Exploration rovers, Spirit and Opportunity, which have been traversing the Mars surface since January 2004.

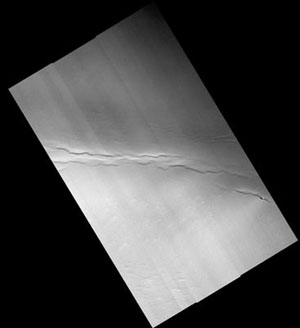

Some of the first radar and imaging results from the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter show details in layers of ice-rich deposits near the poles. Observed variations in the layers’ thickness and composition will yield information about recent climate cycles on the red planet.

NASA’s Mars Exploration Rover Opportunity has photographed patterns in the layering of crater-wall cliffs that are the clearest evidence of ancient sand dunes the rover has seen since arriving at Mars nearly three years ago. The science team for Opportunity’s twin, Spirit, is using new orbital images of the rover’s surroundings to interpret how some rocks with minerals altered by water fit into the area’s complex layered structure.

“The combination of instruments on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter is such a great advantage,” said Jack Mustard of Brown University, Providence, R.I. He is deputy principal investigator for the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer for Mars, a mineral-identifying instrument on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter. Researchers are using mineral information from analyses of spectrometer observations, combined with images from the orbiter’s High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment, to seek the source of the mineral gypsum in dunes near the Martian north pole and clay minerals elsewhere. Gypsum and clay minerals are indicators of formerly wet conditions.

Other new images from that camera show mysterious pitting in the layered terrain near the north pole. Nearby, a steep slope exposing the layers appears to be shedding blocks of icy material that disappear instead of accumulating at the bottom of the slope.

“Observations of the polar layered deposits are telling us about the material properties there,” said Ken Herkenhoff of the U.S. Geological Survey, Flagstaff, Ariz. “These deposits record relatively recent climate variations on Mars, like recent ice ages on Earth.”

The Shallow Subsurface Radar instrument on Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter has begun probing through similar layered deposits at Mars’ south pole. “The radar is penetrating through the entire thickness of these deposits and revealing the fine-scale internal layering,” said Phillips of Washington University.

Far from the poles, Opportunity is navigating the scalloped rim of Victoria crater about half a mile in diameter, stopping at promontories along the way to look at cliff walls of adjacent promontories. The top part of the stack of layers exposed in the cliffs appears to be rocky rubble thrown outward by the impact that dug the crater. “We see an abrupt transition between the jumbled-up material and intact layers below it that are still in place from before the impact,” said Steve Squyres of Cornell University, Ithaca, N.Y., principal investigator for the rovers. Some of the intact layering resembles fossilized dunes in the U.S. Southwest.

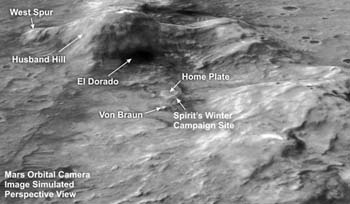

Spirit recently found water-altered minerals in disturbed soils and granular rocks near where the rover spent the Martian winter. An image of the region from Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter is aiding interpretation of how different parts of the terrain, such as a bright platform nicknamed “Home Plate,” are related to others.

“It appears likely that these rocks came from one or more volcanic explosions that produced ‘Home Plate,'” said Arvidson of Washington University.

John Callas of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, Pasadena, Calif., project manager for the rovers, said, “The biggest news about the health of the rovers is that it is essentially unchanged from nine months ago. Each rover has operated more than 1,000 Martian days on the surface of Mars. They are well past their original design life of 90 Martian days, and there is always the possibility that a critical component on either rover could stop functioning at any time, so we operate the rovers with that in mind and value each additional day they continue to work.”

Researchers are describing the latest findings of Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and the twin rovers today at the American Geophysical Union meeting in San Francisco. New images from the orbiter and rovers can be seen at: http://www.nasa.gov/mission_pages/MRO/news/mro-20061213.html .

JPL, a division of the California Institute of Technology, manages the Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter and Mars Exploration Rover missions for the NASA Science Mission Directorate, Washington. Lockheed Martin Space Systems, Denver, is the prime contractor for the orbiter. The Johns Hopkins University Applied Physics Laboratory, Laurel, Md., provided and operates the Compact Reconnaissance Imaging Spectrometer. The High Resolution Imaging Science Experiment is operated by the University of Arizona, Tucson, and the instrument was built by Ball Aerospace and Technology Corp., Boulder, Colo. The Shallow Subsurface Radar was provided by the Italian Space Agency and its operations are led by the INFOCOM Dept., University of Rome “La Sapienza.”