Abolitionist William Wilberforce once wrote “Things great have small beginnings.”

Washington University could be a prime example of what Wilberforce meant.

The precursor to Washington University, Eliot Seminary, started out as just one building — Academic Hall — at the intersection of 17th Street and Washington Avenue in downtown. The building opened for classes in 1856, three years after Missouri Gov. Sterling Price signed into law the charter incorporating the school.

Shortly after — Feb. 12, 1857, to be exact — Gov. Trusten Polk signed into law the amended charter renaming the school Washington University, and an era was begun.

The city, the school and the student body all began to grow. And over the next four decades the realization set in that the school would need to relocate to a place that had more space.

Plus, the downtown area was becoming less suitable as many St. Louisans moved away to escape the air pollution, dirt and din of a typical 19th-century inner city. The new streetcar line on 18th Street shook the physics lab and observatory.

In spring 1892, Robert S. Brookings, Edward Rowse, Henry W. Eliot and William Huse formed a committee to find a new site for the University. The following June, they located 103 acres just beyond the western limits of the city — which would cost $185,000.

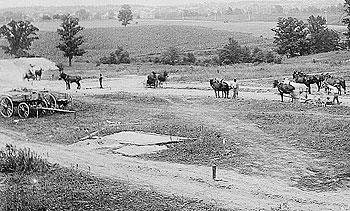

It was far from a sure thing — Skinker Road had yet to be paved so it turned into a muddy mess every time it rained, and the west end of Forest Park was known as the “Wilderness.”

But the hilltop vantage point reminded several of the Acropolis in Greece, and it didn’t take long for construction on the new home of Washington University to start.

The issue of design was still to be determined. The University hired the firm of Frederick Law Olmsted from Massachusetts to develop a site plan, which included buildings with adjoining quadrangles.

Six architecture firms were invited to submit plans for the campus, and Cope and Stewardson — which had designed buildings for Bryn Mawr College, the University of Pennsylvania and Princeton University and favored the Collegiate Gothic style — was unanimously chosen.

Much work needed to be done before construction started. Workers moved a million cubic yards of soil, adding 12 feet to the main quadrangle alone to raise it to its intended height.

The cornerstone for Busch Hall, the first building of the new Hilltop Campus, was laid Oct. 20, 1900.

Other buildings quickly followed: Brookings had pledged $200,000 for an administration building (then called University Hall, now Brookings Hall), and $100,000 each had come from Adolphus Busch, board member and founder of Anheuser-Busch Brewing Co., for a chemistry building; Elizabeth Liggett for a men’s dorm in honor of her husband, president of Liggett & Myers tobacco company; and British-born lamp magnate Stephen Ridgley, who bequeathed $66,000 to the University for a new library. Samuel Cupples, a business partner of Brookings, gave $250,000 for two engineering buildings that would bear his name, plus a laboratory annex.

The two Cupples cornerstones were laid May 11 and 25, 1901, and the following month — on June 15 — the construction was begun on Liggett Hall (later renamed Prince Hall), a dormitory to accommodate 75 men.

But the University quickly ran into financial difficulties. Always one to come up with a solution, in 1901 Board President Brookings leased the new buildings to the Louisiana Purchase Exposition Co. to serve as its headquarters for the World’s Fair, which was held April 30-Dec. 1, 1904.

The deal gave the University $650,000 in rent, $500,000 of which would support the construction of three more buildings, also to be leased by the Exposition company. If the fair was postponed a year from its intended start of 1903, the company would add $100,000, which would pay for a fourth building.

Ridgley Hall went up in 1902; also rising that fall were Tower Hall Dorm (later named for board member John F. Lee, then for St. Louis businessman and philanthropist Karl Umrath) and the gymnasium, named for David Francis, an 1870 graduate of the University, governor of Missouri, mayor of St. Louis, president of the Louisiana Purchase Exposition Co., U.S. ambassador to Russia and president of the Merchants Exchange.

Only a short time after the World’s Fair, on Jan. 30, 1905, services in the chapel — then the oak-paneled room over the University Hall arch (now the Chancellor’s Room) — inaugurated academic use of the campus.

Buildings that soon followed included an observatory, McMillan Hall (a women’s dorm, completed in 1907) and Graham Chapel, completed in 1909 and modeled after the considerably larger Kings College Chapel at Cambridge University.

In 1908, Chancellor David Houston had some big ideas for the campus. He wanted a strong graduate program, an extensive library and perhaps foremost, a broader geographical reach.

The next year, Houston moved the law school and the School of Fine Arts from their downtown locations to the Hilltop Campus. The law school moved into Ridgley Hall; fine arts moved to what had been the British Pavilion, left over from the World’s Fair and located just to the north of where Bixby Hall was later built.

Brookings later gave the University 50 acres south of Forsyth Boulevard, which saw two homes go up — Blewett Hall and Brookings’ own home, Cecilwood, which is now the Alumni House. A half-century later, much of this land would become what is now called the South 40.

Enrollment surges

Following World War I, the University experienced an upturn in student enrollment, up to 3,000 — 700 more than in 1918. More buildings were needed to help ease the pressures of expansion.

In 1920, construction started on Duncker Hall — to memorialize Charles Duncker (A.B., 1914), who was killed in the war — and was completed in 1924 to serve as the School of Commerce and Finance. In short order followed January Hall (1923), Wilson Pool, Wilson Hall and the Women’s Building.

Student housing was an issue as well, so the first five of nine fraternity houses were completed in 1925.

The following year was another big year for construction on campus. Earlier, William Bixby had pledged $250,000 toward the construction of an Art School Building, which was completed in 1926. Also in 1926, the Field House was dedicated and construction began on Rebstock Hall, which was to house zoology and botany.

Givens Hall opened in late 1932, and the next year, Edward Mallinckrodt Jr. and Malvern Clopton donated $700,000 anonymously to construct a new physics building, Crow Hall, which opened in 1934. Eads Hall then became the home of psychology, education and philosophy.

In 1935, work began on a social work building, which included a 200-seat lecture hall and a 500-seat public auditorium. Bettie Bofinger Brown honored her late husband, George Warren Brown, and the building had a feature she designed herself — a second-floor social room, today known as Brown Lounge. Completed in 1937, the building was said to be the first in the United States built solely for the purpose of social work. In the beginning, though, it also housed history, political science, sociology and anthropology.

In 1938, physicist Arthur Hughes recommended to Chancellor George C. Throop that the University build an 80-ton cyclotron to produce radioisotopes that could be used in medical and biological research. In early 1940, the University broke ground for an underground chamber just west of the Power Plant on the Hilltop Campus. Late in 1941, it was finished and was used to isolate the world’s first plutonium, albeit in microscopic amounts.

Similar to the aftereffects of World War I, at the conclusion of World War II, student enrollment reached new levels. With more students and more classes, the University needed to attract more faculty.

One of the enticements for recruiting faculty was the appeal of free housing — and in December 1945, workers assembled 20 temporary housing units on the northwest end of campus; another 30 went up the following spring.

Also that following spring, construction began on a radiochemistry lab, funded by Monsanto, and the Department of Music was placed into Blewett Hall.

Two years later, in 1948, the cornerstone for the Sever Institute of Technology was laid. Sever Hall was finished in 1950 and the Department of Chemistry had Louderman Hall, dedicated in 1952 with an underground laboratory, three-story tower and the first elevator on campus.

Also around this time, the observatory moved to the roof of Crow Hall, while Busch Hall was renovated for economics and history.

By this time, the library — housed in Ridgley Hall — was woefully short of space. Ridgley had been built for 70,000 volumes to be used by a student body numbering about 300. And according to Chancellor Ethan A.H. Shepley, “we now had a student body of 5,000 and a collection of volumes — over a half a million.”

So, the plans for Olin Library were put in motion. Designed by the firm of Murphy and Mackey, groundbreaking for Olin Library took place in 1960 and the building was completed in 1962.

Other buildings started around this time included Urbauer Hall for engineering and Busch III lab of biology. The University’s art collection, on loan to the Saint Louis Art Museum, acquired exhibit space in the new Steinberg Hall, designed by Fumihiko Maki. Other Hilltop Campus additions included the Gaylord Music Library and a donated home for the chancellor, now known as Harbison House.

Out-of-state students

Shepley saw the financial value of attracting out-of-state students and knew that an infusion of students would have a stabilizing effect on faculty. So the architecture firm HOK designed the first of more than a dozen new residence halls — Liggett, Koenig, Umrath, Rubelmann and half of Wohl Center went up between 1958-1960.

Lee, Beaumont, Hitzeman and Myers houses and Building H rose from 1960-62; Shanedling, Dauten and Rutledge houses and the Shepley high-rise residence went up from 1963-64 and the Eliot high rise was completed by the mid-1960s.

Women began vacating McMillan Hall, which became home for economics, anthropology, sociology and education, all in Arts & Sciences, and men left Umrath, which now housed the Student Health Service.

In the 1960s, the Ridgley Hall reading room took on new life as Holmes Lounge.

In 1965, physicist and University provost George Pake won a $3.9 million grant from the National Science Foundation, half of it to help construct buildings in engineering and chemistry — Bryan Hall and McMillan Hall.

The Arthur Holly Compton Lab of physics, Beaumont Pavilion and Monsanto Lab for the Life Sciences also went up in these years, while plans were under way for a student union/performing arts building — Mallinckrodt Student Center — which went up in 1973.

Mudd Hall housed the School of Law from 1972-1997, when Anheuser-Busch Hall was completed and the law school moved. The Mudd building has been replaced by the Charles F. Knight Executive Education Center.

Eliot Hall, dedicated in April 1974, still houses the departments of Political Science and Economics, as well as the Murray Weidenbaum Center on the Economy, Government, and Public Policy in Arts & Sciences.

April 1983 saw the groundbreaking for the Athletic Complex, including a multipurpose gym, swimming pool, racquetball and squash courts. New student housing went up on the South 40 about this time, and in 1985, groundbreaking for the $13 million business school occurred.

The business school had been housed in Prince Hall — a renovated dorm — since 1961. The new business school home, Simon Hall, represented a shift from the modernist concrete Mudd and Eliot halls and Mallinckrodt Center, namely a return to the red granite and limestone building in the Collegiate Gothic style of the first buildings on the Hilltop. Simon Hall was completed in 1985.

The past 10 years have seen more growth on campus: the psychology building was dedicated in 1996; Anheuser-Busch Hall (School of Law) in 1997; Goldfarb Hall (social work) in 1998; and the Charles F. Knight Executive Education Center in 2001.

Shared interest housing

Also opening in 2001 was Small Group Housing, now known as The Village. The Village offers students the unique perspective of living in interest groups of 4-24 members who share a common passion and strive to incorporate that into their everyday lives.

The original goals of The Village were to foster a seamless living and learning environment for students and to complement the curriculum and in-class learning by allowing them to live in these interest groups. Included in The Village is the Lucy and Stanley Lopata House, dedicated in 2001.

Two new residential colleges — Wayman Crow Residential College (comprising Dardick House, dedicated in 2006, and Nemerov House, completed in 2004) and Liggett/Koenig Residential College (2005-06) were built on the South 40.

Other buildings constructed — or starting construction — in the past few years include Uncas A. Whitaker Hall for Biomedical Engineering (completed 2002); Arts & Sciences Laboratory Science Building (2002); Earth and Planetary Sciences Building (2004); and the Sam Fox School of Design and Visual Arts (2006, which includes the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum and the Earl E. & Myrtle E. Walker Hall).

And Olin Library saw a massive renovation, in the process acquiring 17,000-square-feet of space on the main level.

In all, more than $1.5 billion in new buildings and renovations have taken place in the last dozen years the Danforth and Medical campuses.

“The Danforth Campus is a hugely important asset for Washington University,” Chancellor Mark S. Wrighton said. “It is beautiful and supportive of a great environment for learning and discovery, residential life for undergraduates and a setting for the entire St. Louis community to become a part of a research university and its intellectual, cultural and creative programs engaging some of the world’s most talented students and faculty.

“Future generations will work hard to steward this important asset to bring honor to the Danforths and to support our University missions of education, research and service to our community.”

Information for this story was taken from the history book Beginning a Great Work: Washington University in St. Louis, 1853-2003 by Candace O’ Connor.