A Washington University pediatrician at St. Louis Children’s Hospital has found that performing MRI scans on pre-term infants’ brains assists dramatically in predicting the babies’ future developmental outcomes.

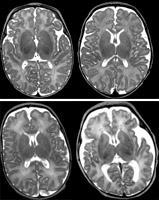

Terrie E. Inder, M.D., associate professor of pediatrics, of radiology and of neurology at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, and pediatric researchers in New Zealand and Australia found that the magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans were able to determine abnormalities in the white matter and gray matter of the brains of very pre-term infants, those born at 30 weeks or less. Following the infants from birth to age 2, the researchers were able to grade those abnormalities to predict the risk of severe cognitive delays, psychomotor delays, cerebral palsy, or hearing or visual impairments that may be visible by age 2.

The results of the study appear in the Aug. 17 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine.

The researchers studied 167 preterm infants in New Zealand and Australia and at St. Louis Children’s Hospital.

Inder said the findings are a breakthrough because previous technology – cranial ultrasounds – did not show the abnormalities in the infants’ brains.

“With the MRI, now we can understand what’s going wrong in the developing brain when the baby is born early,” Inder said. “We can use the MRI when the baby reaches full-term (40 weeks) to predict neurodevelopmental outcomes.”

More than 2 percent of all live births are infants born before 32 weeks of gestation. Nationwide, the rate of premature births jumped 13 percent between 1992 and 2002, according to the March of Dimes. Recent data show that 50 percent of children born prematurely suffer some neurodevelopmental challenges, such as crawling, walking upright, running, swinging arms, and other activities that require coordination and balance. Among pre-term infants who survive, 5 percent to 15 percent have cerebral palsy, severe vision or hearing impairment or both, and 25 percent to 50 percent have cognitive, behavioral and social difficulties that require special educational resources.

The MRI scans show lesions on the infants’ brains, as well as which region of the brain is affected and the severity of the risk for future developmental delays. For example, if a lesion is in the area of the brain that controls fine and gross motor skills, the risk is higher that the child will have some type of developmental delay in movement. Pediatricians would then know that the child would benefit from immediate physical therapy, Inder said.

“We can use these results to determine which baby would benefit most from physical, occupational or speech therapy,” Inder said. “We can also help prepare the parents for future challenges with learning delays and developmental disabilities.”

Woodard LJ, Anderson PJ, Austin NC, Howard K, Inder TE. Neonatal MRI to Predict Neurodevelopmental Outcomes in Preterm Infants. New England Journal of Medicine 355;685-94. Aug. 17, 2006.

This research was supported by the Neurological Foundation of New Zealand, the Lottery Grants Board of New Zealand, the Canterbury Medical Research Foundation, the Health Research Council of New Zealand, the Murdoch Children’s Research Institute and the National Health and Medical Research Council of Australia.

Washington University School of Medicine’s full-time and volunteer faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals. The School of Medicine is one of the leading medical research, teaching and patient care institutions in the nation, currently ranked fourth in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.