For years, the St. Louis region has attempted to promote itself as a new biotechnology hub. But if that is the case, how aligned are the local human resource development strategies with the economic goals of the area? If St. Louis does become a great biotechnology hub, where will the scientifically literate workforce come from?

These are the questions that William F. Tate, Ph.D., the Edward Mallinckrodt Distinguished University Professor in Arts & Sciences, attempts to answer.

A mathematics educator and social scientist by training, Tate has made great strides in furthering the advancement of mathematics and science education research since he arrived on campus in 2002 as chair of the Department of Education in Arts & Sciences.

Tate, who also is professor of American Culture Studies in Arts & Sciences, is interested in examining the relationship between a city’s economic goals — in particular those goals that require significant technological advancement — and the civic actions that limit or accelerate human resource capacity to achieve the stated goals.

Understanding the state of affairs in mathematics and science education is a vital aspect of this work.

“If St. Louis claims it wants to be the next biotechnology corridor, then I want to understand what mechanisms are put in place to provide local people with the technological skills necessary to make that a reality,” Tate says.

The center he directs, the St. Louis Center for Inquiry in Science Teaching and Learning (CISTL), conducted a study of Missouri Assessment Program (MAP) science test scores from 30 local school districts. The data showed that scores in science proficiency were sorely lacking by the time students reached 10th grade.

A similar study has just been conducted on the mathematics skills of the region’s youth, and the report card is not much better.

Knowing the science attainment of students is important for understanding how students are being prepared for science-related coursework in college and for science, engineering and technology jobs both before and after college, Tate claims.

“High school graduates proficient in science are critical if our region is going to accomplish the goal of being a biotechnology hub,” he says. “Additionally, community members with strong science backgrounds also might be more inclined to support science initiatives. It is hard to support what you don’t understand.”

Born in Chicago, Tate earned a bachelor’s degree in economics from Northern Illinois University in 1982. He earned a master’s degree in mathematical sciences from the University of Texas, Dallas, in 1987, and a doctorate in mathematics education from the University of Maryland in 1991.

He then was hired as a professor of mathematics education at the University of Wisconsin, a position he held for 10 years. In 1999, while still employed by Wisconsin, he served as scholar-in-residence and assistant superintendent-mathematics and science in the Dallas Independent School District.

In 2001, Tate was named the William L. and Betty F. Adams Chair and professor of mathematics education and mathematics at Texas Christian University, before coming to WUSTL.

He is very excited about the progress the Department of Education has made since his arrival.

“One of the goals I had coming in was to be consistently ranked among the top 50 graduate programs in the nation,” he says. “We have achieved that now for two years running.”

In fact, the department is one of only two education departments — not schools — to be ranked in the top 50 by U.S. News and World Report this year. Cornell University has the other.

In three of the past four years, the department has been ranked in the top 50. The honor is unique in that all other competitors are generally large colleges of education separate from Arts & Sciences.

A second goal of Tate’s was to expand math and science education within the department. In part, this is being accomplished through the collaborative efforts associated with CISTL. The three-year-old center was made possible with a grant from the National Science Foundation. It focuses on supporting inquiry-based teaching and learning in K-12 science through professional development and research.

While housed at WUSTL, CISTL collaborates with the Saint Louis Science Center, Missouri Botanical Gardens, Saint Louis Zoo and other local school districts and universities.

Tate attributes the success of the department to its outstanding faculty and the ability to attract great students.

“Our undergraduate and graduate students have exemplary backgrounds,” Tate says. “The average GRE scores and other academic quality factors associated with our graduate students are very strong. We also are able to provide unique faculty expertise in areas like urban studies, learning and creativity, history of education, policy studies, race and schooling, and science and mathematics education.

“Our teacher/student ratio has been consistently ranked as the best among the top 50 graduate programs. Students want individual attention and to feel like they are part of a smaller learning community.”

In addition, Tate added, the reputation of the University as a whole continues to rise helping to get additional inquiries from more and more potential students.

Tate hopes to continue building the department and to sustain its current trajectory of success.

|

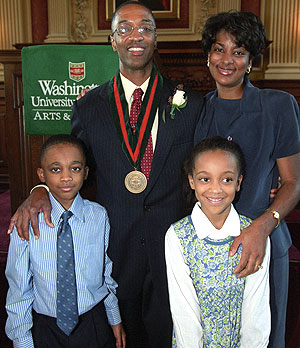

William F. Tate Position: Edward Mallinckrodt Distinguished University Professor in Arts & Sciences, professor and chair of education and professor of American culture studies, both in Arts & Sciences. Hobbies: Basketball and fencing Years at the University: Four Quote: “I really enjoy working with the students. I think they are fantastic. They are up to whatever challenges you provide them and they look to go further.” |

“Accomplishments by faculty and students in the department are really going great right now,” he says. “If we can continue to attract strong faculty with disciplinary backgrounds we can make a huge difference in preparing our undergraduate and graduate students to go out and contribute to the advancement of urban communities, knowledge production, and society.”

Tate was recently elected president-elect of the American Educational Research Association (AERA), a professional society with approximately 25,000 members in the United States and abroad. His term as president starts at the end of the annual meeting next April, after serving as president-elect for a year.

His contributions, both to the University and to society, have not gone unnoticed.

“Bill Tate is terrific,” says Edward S. Macias, Ph.D., executive vice chancellor, dean of Arts & Sciences and the Barbara and David Thomas Distinguished Professor in Arts & Sciences. “He is leading the Department of Education in new and exciting ways. His work on science education is highly respected throughout the country. He is leading the CISTL very dynamically. He is the real deal — a great faculty member.”

Tate thoroughly enjoys being a part of the WUSTL community.

“I really value my personal relationships with colleagues across campus,” he said. “I like the fact that you can work across programs very easily. It’s easy to get involved in a wide swath of programs that meet your intellectual needs but may also facilitate meeting the needs of students. It’s a very nice community of learners and researchers.

“I also really enjoy working with the students. I think they are fantastic. They are up to whatever challenges you provide them and they look to go further.”

When he’s not focused on the political and economic dimensions of science and mathematics education, Tate enjoys playing basketball in the noon hoops game at the Athletic Complex and is taking fencing lessons with his 9-year-old son, Quentin.