When a child inherits an abnormal gene that leads to thyroid cancer, surgical removal of the thyroid gland before the cancer spreads is the only sure cure. Now a new study shows it is best to take out the thyroid before a child turns 8 years old to guarantee a life free of thyroid cancer.

The study was published in the New England Journal of Medicine by researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis and Duke University School of Medicine.

“This is a prime example of the new age we are entering in which genetic information can guide surgical practice,” says Jeffrey F. Moley, M.D., associate director of clinical investigations at the Siteman Cancer Center and professor of surgery at Washington University and Barnes-Jewish Hospital in St. Louis. “In the case of this disorder, we rely on a simple genetic sequencing test to tell us a patient needs surgery. Our group was among the very first to follow this paradigm.”

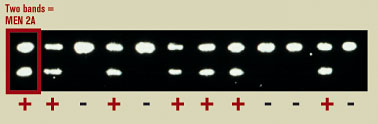

All of the children in the study had mutations of the RET gene that cause multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A (MEN 2A). If untreated, individuals with MEN 2A invariably develop progressive growth of cells in the thyroid gland, which are responsible for producing the hormone calcitonin. Overgrowth of calcitonin-producing cells in the medulla progresses to a malignant condition called medullary thyroid carcinoma, which soon spreads to nearby lymph nodes and then to other areas of the body.

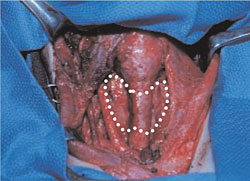

The researchers tracked the effectiveness of preemptive thyroid removal in 50 at-risk children ranging in age from 3 to 19 years. All patients were followed for at least five years at Washington University School of Medicine and at Duke University School of Medicine. The surgeons found that none of the 22 children who were under 8 at the time of surgery showed signs of thyroid cancer five or more years later. However, they did find indications of thyroid cancer in six of the 28 children who were older than 8 when they had surgery to remove the thyroid gland.

As standard procedure, the surgeons also removed lymph nodes from the central zone of the neck in all but one of the study patients. Cancer cells were found in the lymph nodes in only three patients at the time of surgery: One of these patients was 10 years old, and the other two were 11. Two of these patients were among those who showed signs of recurrence of thyroid cancer years later, suggesting better prognosis if surgery is done before the cancer has spread to lymph nodes.

According to Moley, the study suggests that when surgery is done in young children — before any cancer has spread to the lymph nodes — the nodes can be left in place. This reduces the risk of long-term effects from more extensive surgery, which can damage the nearby parathyroid glands or nerves to the vocal cords.

After thyroidectomy, patients must take thyroid hormone pills to replace the hormone produced by the gland, but thyroid removal has no other side effects.

“Our study strongly suggests that surgery should be performed on children with mutant RET genes before they are 8,” Moley says. “We followed these children for at least five years and will continue to follow them throughout their lives. The study was very carefully designed and carried out, and we believe it lends significant weight to the hypothesis that removing the thyroid early saves lives.”

Skinner MA, Moley JA, Dilley WG, Owzar K, DeBenedetti MK, Wells SA. Prophylactic Thyroidectomy in multiple endocrine neoplasia type 2A. New England Journal of Medicine, Sept. 15, 2005.

Funding from the National Institutes of Health supported this research.

Washington University School of Medicine’s full-time and volunteer faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals. The School of Medicine is one of the leading medical research, teaching and patient care institutions in the nation, currently ranked third in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.

Siteman Cancer Center is the only NCI-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center within a 200-mile radius of St. Louis. Siteman Cancer Center is composed of the combined cancer research and treatment programs of Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Washington University School of Medicine.