Physicians treating women with breast cancer recognize the need for a specific and sensitive method to monitor disease recurrence, so they should be encouraged by a new study that describes a biomarker that seems to fill those criteria.

Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis have shown that mammaglobin, a protein secreted by breast tumor cells, can readily be detected in the blood serum of patients with metastatic breast cancer using an inexpensive, reliable clinical test.

“A test for mammaglobin holds significant promise for catching metastatic tumors early,” says study co-author Timothy P. Fleming, Ph.D., research associate professor of surgery at the School of Medicine and a researcher with the Siteman Cancer Center. “Compared to the few other known biomarkers linked to breast cancer, mammaglobin is the best. The protein is found in breast tissue and is secreted by most breast tumors.”

The study, published in Clinical Cancer Research, tested 56 women without breast cancer and 26 women with metastatic breast cancer. The women without breast cancer were found to have a steady, low level of mammaglobin in their blood. This baseline level was not affected by age, body mass index, menopausal status, race, smoking history or a family history of breast cancer.

In contrast, the women with metastatic breast cancer had on average much higher readings of mammaglobin than the baseline level, providing the potential to distinguish cancer-free patients from those with recurrent breast tumors.

In addition, about 80 percent of all breast cancers examined, regardless of the type of tumor or stage of development, tested strongly for mammaglobin while normal breast tissue had significantly less mammaglobin. Prostate, colon, lung and ovarian cancer tissues did not test positive for mammaglobin.

Physicians believe an ideal disease screening method should be simple, noninvasive and use components that are stable under a variety of conditions. This study shows that mammaglobin levels in blood serum can be readily obtained with a test called ELISA, an inexpensive clinical test often used to measure protein levels in fluids.

The test detected even very low concentrations of mammaglobin in blood serum and maintained accuracy over a 1,000-fold increase of mammaglobin concentration. Serum samples subjected to repeated freezing and thawing or stored frozen for a year tested just as effectively as fresh samples, indicating no potential problems with sample storage.

Discovering mammaglobin

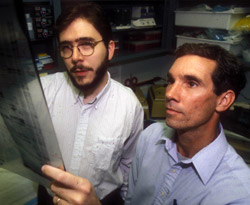

Mammaglobin was discovered in Fleming’s laboratory in the late 1990s through the efforts of Fleming and then-postdoctoral associate Mark A. Watson, M.D., Ph.D.

“Originally, we identified the gene that produces mammaglobin because it is activated in breast cancer relative to non-malignant breast cells,” says study co-author Watson, associate professor of pathology and immunology and director of the Multiplexed Gene Analysis Core and Tissue Procurement Core at Siteman. “When we studied it further, we saw that the gene is predominantly active only in breast tissues and realized it would be an important marker for breast oncology research.”

Mammaglobin has since become the subject of more than 100 independent scientific articles.

“It’s exciting to be a part of the research developments surrounding mammaglobin,” Fleming says. “Groups are looking at its potential in a variety of diagnostic circumstances as well as in creating a breast cancer vaccine. Next, we are planning to work on high-throughput techniques to test our mammaglobin blood test in a much larger study.”

Bernstein JL, Godbold JH, Raptis G, Watson MA, Levinson B, Aaronson SA, Fleming TP. Identification of mammaglobin as a novel serum marker for breast cancer. Clinical Cancer Research, 2005;11(18):6528-6535.

Funding from the Breast Cancer Research Foundation, the National Cancer Institute and the National Institutes of Health supported this research.

Washington University School of Medicine’s full-time and volunteer faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals. The School of Medicine is one of the leading medical research, teaching and patient care institutions in the nation, currently ranked third in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.

Siteman Cancer Center is the only NCI-designated Comprehensive Cancer Center within a 240-mile radius of St. Louis. Siteman Cancer Center is composed of the combined cancer research and treatment programs of Barnes-Jewish Hospital and Washington University School of Medicine.