Children activate different and more regions of their brains than adults when they perform word tasks, according to investigators at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis.

Reporting in the journal Cerebral Cortex, the researchers say those changes in regional brain activity from childhood to adulthood may reflect the more efficient use of our brains as we mature.

“Basically, when children accomplish these same tasks with performance levels comparable to the adults, they do so with a different set of brain regions; that is, a different functional neuroanatomy,” says principal investigator Bradley L. Schlaggar, M.D., Ph.D., assistant professor of neurology, of pediatrics, of neurobiology and of radiology.

To see how the functional neuroanatomy changes with age, Schlaggar, along with Steven E. Petersen, Ph.D., the James S. McDonnell Professor of Cognitive Neuroscience, and their colleagues scanned 95 subjects with functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI). Inside the scanner, the study subjects, ages 7 to 32, performed three word-generating tasks: rhymes (say “cat” in response to “hat”), opposites (say “up” in response to “down”), and verb generation (say “drive” in response to “car”).

As the subjects saw or heard a test word and spoke the correct response, an fMRI scanner took “snapshots” of their brain activity. The scanner detects changes in blood oxygenation levels that correlate with local changes in the brain’s activity.

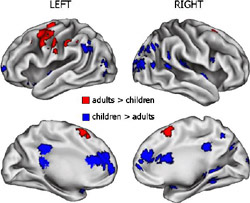

Children and adults were compared according to performance level, defined by the number of correct answers and the time it took to complete a word task. Then, the researchers compared the fMRI snapshots of children and adults who were similarly good at the three tasks. Brain activity varied between people of different ages, even though they were performing the same tasks at a similar level of proficiency. Relative to adults, children tended to use more regions of their brains to complete the word tasks, activating more regions near the back of the brain. At the same time, children showed less activation in some regions at the front of the brain that have been commonly seen in adult studies of word processing.

In some brain regions, children and adults showed very similar levels of activation while performing the tasks. This included some parts of the frontal lobe.

“This is particularly interesting because research on structural brain development has suggested that the frontal lobe is relatively slow to mature,” Schlaggar says.

Because of this protracted development, many experts assumed children did not use their frontal lobes as adults do. However, this new research suggests that large areas of the frontal lobe function similarly in children and adults when performing these tasks.

“We were surprised by the locations of many of the similarities and differences,” says first author and graduate student Tim Brown. “We found that a few brain regions ‘grow up’, that is are used more frequently as we mature. Other regions ‘grow down’, or become less active, and some appear to stay the same across these ages.”

Brown says they also found preliminary evidence that suggests, for these tasks, some regions at the front of the brain mature earlier than some at the back. That also was unexpected because of earlier structural data.

These new observations are made possible by recent improvements in fMRI scanning. In the earlier scanning method, the fMRI scanner took images for long periods of time, similar to leaving the shutter open on a camera. Although researchers could detect brain activity, they could not discern how the brain reacted to a specific stimulus.

In the “event-related” fMRI method used in this study, the scanner takes a series of quick snapshots three seconds apart. This allowed Schlaggar, Brown and colleagues to discern what parts of the brain were activated as it was stimulated by the word-generation tasks and, importantly, allowed them to distinguish brain activity related to different levels of performance.

The researchers hope their observations may help them to understand normal brain function in order to compare those baseline observations with the brain function seen in atypically developing children with Tourette Syndrome, cerebral palsy and other conditions that can interfere with normal cognitive development.

Brown TT, Lugar HM, Coalson RS, Miezin FM, Petersen SE, Schlaggar BL. Developmental changes in human cerebral functional organization for word generation. Cerebral Cortex: 15; 275-290, March 2005.

This research was funded by grants from the National Institutes of Health, National Science Foundation, ,the John Merck Scholars Fund, the Burroughs-Wellcome Fund, the McDonnell Center for Higher Brain Function and the Charles A. Dana Foundation.

Washington University School of Medicine’s full-time and volunteer faculty physicians also are the medical staff of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals. The School of Medicine is one of the leading medical research, teaching and patient care institutions in the nation, currently ranked third in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.