A controversial theory about how diabetes causes extensive tissue damage will appear in the November issue of Diabetes. At stake in the heated debate over the theory are researchers’ efforts to find new ways to reduce loss of vision, kidney failure, heart damage and other side effects of diabetes.

The American Diabetes Association estimates that 18.2 million Americans have diabetes. Diabetes’ links to heart attack and stroke make it the sixth leading cause of death, and it is the leading cause of new cases of blindness among adults 20-74 years old. Diabetic nerve damage is a major contributor to non-traumatic lower limb amputations, and diabetic kidney damage creates 43 percent of all cases of end-stage renal disease.

Proponents of the theory argue that the primary cause of such tissue damage is a key compound in energy production other scientists long ago rejected as a contributor to diabetic side effects. The researchers address the many objections and questions raised by critics of their hypothesis in a 47-page appendix available online in conjunction with their study.

“The metabolic imbalances caused by diabetes are quite complex, and that has made it very difficult to gain acceptance or even consideration of our hypothesis,” says senior investigator Joseph Williamson, M.D, a retired pathology faculty member at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis. “Being able to publish the online appendix finally gave us the room we needed to respond to everyone’s concerns.”

Williamson’s theory focuses on the energy-producing compound’s reversible transformation between two forms, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) and NADH (NAD plus H, or one atom of hydrogen). Cells transform NAD into NADH when they transfer electrons and protons from the sugar glucose to NAD during an energy-making process called glycolysis.

This process doesn’t require oxygen, but it needs NAD to get started. Cells therefore make it a top priority to keep high amounts of NAD available.

“The ratio of NAD to NADH varies in different types of tissues, ranging from 500 to 1 to 2,000 to 1,” Williamson notes. “In diabetics, though, that ratio can drop as low as 200 to 1.”

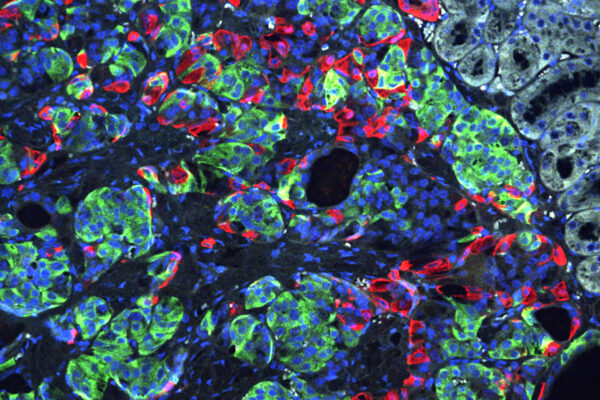

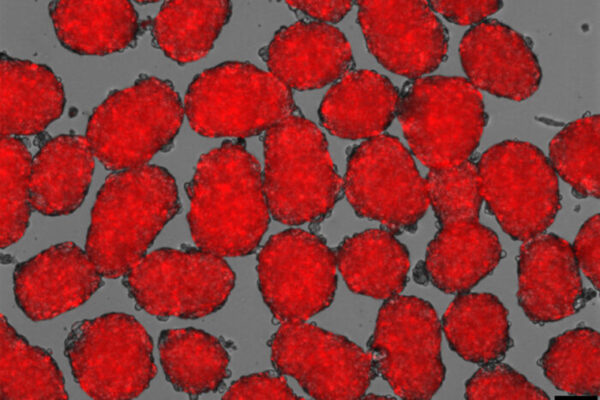

In diabetic patients, blood sugar levels are elevated, a condition known as hyperglycemia; in addition, tissues damaged by diabetes often have low levels of oxygen, or hypoxia. Williamson and his coauthors used in vitro studies of rat retinas to show that both of these conditions decrease the ratio of NAD to NADH in different ways. Hyperglycemia does it by increasing the rate of transformation of NAD to NADH. Hypoxia makes it difficult for cells to turn NADH back to NAD.

In both conditions the increased NADH is recycled back to NAD by processes that produce free radicals, chemically reactive compounds that can damage tissue. Williamson and his coauthors propose that long-term use of these processes causes the damage seen in diabetes.

“The consequences of these different disruptions to NADH recycling are additive–they have the potential to produce much more damage than you might expect if you looked at either one independently,” Williamson explains.

Scientists have known for some time that diabetes increases transformation of NAD to NADH by boosting cells’ consumption of glucose through a process known as the sorbitol pathway.

Like glycolysis, the sorbitol pathway transforms NAD to NADH, but only at a small fraction of the level of glycolysis. This previously led scientists to conclude that the sorbitol pathway was highly unlikely to create enough NADH to trigger the recycling processes that create free radicals.

Williamson counters that glycolysis makes pyruvate as well as NADH, and pyruvate transforms NADH back to NAD. The sorbitol pathway doesn’t make pyruvate, so the NADH it makes has to be recycled by other processes that create free radicals.

“If you make a normal animal hyperglycemic by infusing glucose into it for five hours or so, you’ll see some of the same changes in the blood vessels that you see very early on in diabetics,” Williamson notes. “However, we showed that if you infuse pyruvate at the same time you infuse the glucose, you completely block those changes.”

Pyruvate also protects tissues from much of the damage normally caused by hypoxia, which leads to many of the same changes in blood vessels and other tissues caused by diabetes.

“We’ve still got quite a bit of convincing to do, but I think people are starting to recognize that this seems to be a major mechanism for producing the free radicals that play such an important role in diabetic complications,” Williamson says. “Hopefully this will someday lead to more success in efforts to ease those complications.”

Nyengaard JR, Ido Y, Kilo C, Williamson JR. Interactions between hyperglycemia and hypoxia: implications for diabetic retinopathy. Diabetes, November 2004.

Funding from the National Institutes of Health, Fonden til Laegevidenskabens Fremme, the Lundbeck Foundation and the Kilo Research Foundation.

The full-time and volunteer faculty of Washington University School of Medicine are the physicians and surgeons of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals. The School of Medicine is one of the leading medical research, teaching and patient care institutions in the nation, currently ranked second in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.