“Never imagine problems before they happen,” advises Ming You, M.D., Ph.D., director of the Chemoprevention Program at the Siteman Cancer Center. “Just start in, deal with problems as they come and many times they will be much simpler to solve than you thought.”

His pragmatic philosophy may explain how You rapidly rose from a turbulent childhood in Beijing to his current position. He never considered anything impossible — a useful attitude for a scientist who tackles lung cancer.

The most prevalent — and most deadly — form of cancer, lung cancer kills 90 percent of its victims within three years.

You, also a professor of surgery, came to the Siteman Cancer Center in 2002, recruited by Timothy Eberlein, M.D., director of the center, chairman of the Department of Surgery and the Spencer T. and Ann W. Olin Distinguished Professor, to initiate and head the new Chemoprevention Program.

“Ming is a superb scientist and an extraordinary leader,” Eberlein says. “He has a magnetic personality and seems to attract other talented scientists to work with him. His leadership and accomplishments have been vital as we go through the application process to become a comprehensive cancer center as designated by the National Cancer Institute.”

You’s research at Siteman has two goals: One is to seek genes that contribute to lung-cancer susceptibility, and the other is to look for compounds that can help prevent the disease.

Many promising preventive compounds occur naturally in plants, and You has already set up research collaborations with the region’s major players in plant biology — the Missouri Botanical Garden, the Donald Danforth Plant Science Center and the Department of Biology on the Hilltop Campus.

You has also established projects to test the effects of preventive agents with key groups on the Medical Campus, including the Center for Human Nutrition, the Division of Oncology and the Division of Dermatology.

“We’re pushing every button we can,” You says. “And the Siteman center has everything we need. We have funding, we have laboratory space — we can really get up and running fast here.”

Turning to nature

Among other projects, You will continue his work with a very promising traditional Chinese herbal medicine that has the ability to prevent up to 100 percent of lung tumor progression in high-risk people. The mixture was named Anti-tumor B by the Chinese researcher who first discovered its effect against esophageal tumors.

One challenge has been to identify the active components of Anti-tumor B. You and his collaborators have made significant progress on that front.

“In about three steps, we’ve gone from thousands of unknown compounds (in the raw material) to between 10 to 50 identified compounds that are potentially active,” You says. “Soon we will test these individually and in combination to find those that work best.”

You also maintains research projects with other natural products such as green tea and ginseng, which have shown promise as chemopreventive agents.

You’s work in chemoprevention perfectly complements his research on the causes of lung cancer. Once effective agents are found, researchers can analyze how they prevent tumor progression: Do they block an enzyme? Do they scavenge dangerous free radicals? If so, that points back to the ultimate cause of the cancer.

With medical knowledge of both cause and prevention, people at high risk can be identified, and chemopreventive medicines can be used to greatly reduce the incidence of lung cancer in high-risk groups.

Coming of age

While You has achieved great success, he had a less than auspicious beginning. He was born in Beijing during the famine that resulted from Mao Zedong’s Great Leap Forward. When You was in first grade, the Cultural Revolution began — public demonstrations, skirmishes, purges, imprisonments and forced relocations overturned the established order.

Formal education was disrupted, and no schools were open for about a year and a half. “I was very glad, very happy,” You says with a wink. Unfortunately, even when the schools were reestablished, You did not apply himself to coursework and often just hung out in the streets.

When the chaos of the revolution diminished, You began to be concerned for his future. His high-school graduation was nearing, and it was clear You had no chance of being admitted to a university. He was facing the possibility of being sent to the countryside for “reeducation.”

Then You did what anyone with no fear of failure would do: He got all the elementary, middle and high-school texts he had never read, closed himself in his room and studied — for two months.

“By that time, I thought I knew enough,” he says. “I could do calculus. I could do a lot of things many others who got into college couldn’t do.”

You took the college entrance tests and aced them. Although only about one in 1,000 students would be admitted to college, You earned a place in one of the best medical schools in China, the Beijing Medical College. From then on, You’s can-do attitude and hard work brought him success after success.

Path to success

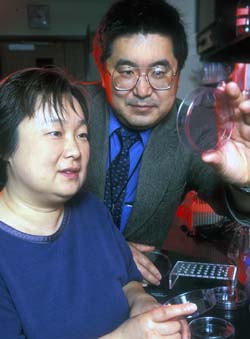

You is married to Yian Wang, M.D., Ph.D., associate professor of surgery, who is also on the faculty of the Siteman Cancer Center researching chemoprevention of breast cancer. Wang often tells people her husband’s life is unusual because good things happen to him that rarely happen to others.

You earned his Ph.D. in 1989 in pathology at the Medical College of Ohio in Toledo. Skipping the usual postdoctoral positions, he was promoted straight to assistant professor of pathology and technical director of the Clinical Molecular Biology Laboratory at the Medical College.

Every few years he advanced another step, to director of the lab, then to associate professor. In 1998, he was promoted to full professor and in 1999 to research director of the Comprehensive Oncology Center. In 2000, he accepted an endowed chair position in lung cancer research at Ohio State University.

You’s mentor, Gary Stoner, Ph.D., professor of hematology and oncology at Ohio State University, says to rise so quickly “you have to be pretty good. Ming You is very ambitious, and I had a hard time keeping him reined in. However, along with a strong work ethic, he brings a great sense of humor. He’s fun to work with.

|

Ming You Titles: Professor of surgery and director of the Chemoprevention Program at the Siteman Cancer Center. Research interests: The genetics and chemoprevention of lung cancer. Education: B.S and M.D., Beijing Medical College, 1982; Ph.D., Medical College of Ohio, 1989. Family: Wife, Yian Wang, M.D., Ph.D., associate professor of surgery; children, Michael, 12, and Helen, 10. |

At first, You will echo his wife’s sentiments, saying his good fortune came as a surprise to him. But, after consideration, You will admit that luck had little to do with his success. While others socialized, he preferred to stay in his office writing papers. He conducted a great deal of research, brought in grants and contracts and served on committees.

You and Wang have two children, Michael and Helen. “They are both good students,” You says, continuing with a laugh, “a lot better than I was.” The children also swim and take music lessons; Michael plays cello and Helen the violin.

True to form, You approaches his kids’ extracurricular activities as an opportunity.

“What I do is take an active role. I take piano lessons while Michael has his lessons,” he says. “When they are at swim practice, I swim in another pool. I enjoy what they enjoy.”

Back in the lab, You’s research keeps yielding new results. Recently, You and his colleagues identified two genes in mice that are associated with an increased incidence of lung tumors.

You’s group, as a member of the Genetic Epidemiology of Lung Cancer Consortium, played a key role in mapping a major lung cancer susceptibility region on chromosome 6 in humans. You calls these discoveries major advances in the field of lung cancer genetics.

You’s success will undoubtedly continue.

“I really enjoy life,” he says. “And, I never think about things too much; I always just do.”