Depression is the most common psychiatric illness in the world, affecting about 15 percent of all people at some point in their lives. Although about 70 percent of depressed patients respond to treatment, three-fourths will experience a recurrence of their illness within 10 years. In addition, an estimated 60 percent of depressed people remain undiagnosed and untreated.

Little is understood about how depression makes people feel sad, but neuroscientists do know that the brain chemical serotonin is involved. Today’s most-prescribed antidepressant drugs — such as Prozac (fluoxetine) and Zoloft (sertraline) — are the so-called selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), which work by increasing serotonin levels in the brain.

“The bad news is that beyond that first step of increasing serotonin, we understand very little about how these drugs relieve symptoms of depression,” says Mark A. Mintun, M.D., professor of radiology and of psychiatry at Washington University School of Medicine. “By pushing on the serotonin system, we seem to start a chain reaction that helps many people, but it doesn’t help everyone. And to learn why, we need to find out more about what’s happening in the brain during depressive episodes.”

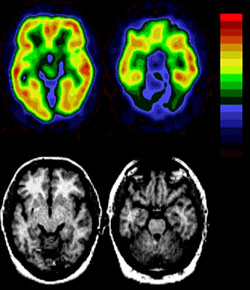

To get a look at how the brain works differently in depressed patients, Mintun and colleagues studied 46 people with active depression and compared positron emission tomography (PET) scans of their brains to scans from 29 people who were not depressed. The team was measuring levels of a particular type of serotonin receptor called the 5-HT2A serotonin receptor.

Mintun has been on the trail of serotonin receptors for years. “The 5-HT2A receptor in this study is the most common of several types of serotonin receptors, so we thought this would be a good place to start,” he says.

Almost a decade ago at the University of Pittsburgh, Mintun and radiochemist Chester Mathis, Ph.D., developed a method of labeling the 5-HT2A serotonin receptor with a chemical called altanserin. The altanserin sticks to the serotonin receptors and allows the PET scanner to take pictures of them.

Because most people with depression get better when their serotonin levels increase after treatment with SSRIs, Mintun initially believed the PET scans would reveal high levels of serotonin receptors in brain structures linked to depression. The hypothesis was that because less serotonin was available, the brain would try to compensate by making more receptors.

But that’s not what they found. In the February issue of the journal Biological Psychiatry, Mintun and colleagues report that the depressed people actually had fewer serotonin receptors throughout the brain and significantly fewer receptors in a key structure called the hippocampus, an area that acts as a gateway between memory and mood, among other processes.

Mark Mintun

“The hippocampus often is the key to interpreting things such as whether an experience is good or bad, whether a person is looking at me with a happy face or a sad face, whether that person is angry with me, those sorts of things,” Mintun says. “So I think the fact that there’s this big drop in the number of serotonin receptors in this part of the brain is telling us something very important.”

Meanwhile, in a parallel series of depression studies, co-author Yvette I. Sheline, M.D., associate professor of psychiatry, radiology and neurology, was learning from magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans of depressed patients that the hippocampus is smaller in patients with depression. Sheline also has found that antidepressant drugs seem to have a protective effect and prevent some of the volume loss she has observed.

Putting it all together, Sheline says the volume loss in the hippocampus might be to blame for the low number of serotonin receptors, rather than the other way around.

“Although it’s clear that serotonin is involved in depression, it may be that the volume loss we have observed is due to damage in cells in the hippocampus, which then cannot process serotonin effectively,” Sheline says. “Perhaps the low number of serotonin receptors is related to cell damage in the hippocampus rather than the damage and volume loss being caused by problems in the serotonin system.”

Mintun and Sheline say it’s still very possible that the low number of receptors is related to an underlying abnormality in the serotonin system, but it’s also possible that the low number of receptors are the result of damage to the hippocampus that is caused by depressive episodes. It also might be that depression results from a process akin to what causes type 2 diabetes. In type 2 diabetes, people still make plenty of insulin, but their insulin receptors don’t work well.

“Those people get diabetes not because they don’t make enough insulin but because the receiving end — the receptors — don’t work as well,” Mintun says. “In diabetes, we give more insulin to overcome that problem, and in depression we raise serotonin levels. But just because raising serotonin levels relieves symptoms of depression, we can’t assume that the original problem was abnormal serotonin production.”

Mintun says preliminary data from studies of depressed people after treatment indicate that the number of serotonin receptors in the hippocampus appears to be rising and returning to normal. But he cautions those studies are preliminary and require more analysis. He also hopes to study other types of serotonin receptors. In particular, he plans to use a new chemical tracer that has been developed to bind to 5-HT1A receptors, which also are found in large numbers in the hippocampus.

Such studies might help explain why SSRI drugs take several weeks to work. If making more serotonin is only one step in a cascade of cellular changes in depression, it might be more effective to treat depressed people by concentrating on some other step in that cascade. But little is known about what those other steps might be.

In addition, better understanding of those additional steps might make it possible to treat people whose depression doesn’t respond to SSRIs and other antidepressant therapies. It also might help scientists understand why depression tends to recur many months, or years, after patients get better.

“There are some important things we need to understand about how these drugs work and how we can make them better,” Mintun says. “Part of that will involve understanding more of the basic biology of what happens during depression and its treatment.”

Mintun MA, Sheline YI, Moerlein SM, Vlassenko AG, Huang Y, Snyder AZ. Decreased hippocampal 5-HT2A receptor binding in major depressive disorder: in vivo measuement with [18F]altanseerin positron emission tomography. Biological Psychiatry, vol. 55, pp. 217-224, February 2004.

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health.

The full-time and volunteer faculty of Washington University School of Medicine are the physicians and surgeons of Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals. The School of Medicine is one of the leading medical research, teaching and patient care institutions in the nation, currently ranked second in the nation by U.S. News & World Report. Through its affiliations with Barnes-Jewish and St. Louis Children’s hospitals, the School of Medicine is linked to BJC HealthCare.