The art world of the 1980s was a place of artistic diversity and aesthetic contention. Neo-expressionists jostled for theoretical (and commercial) position with abstract painters, installation and performance artists, appropriationists and others. And little, upon reflection, was as it seemed.

In January, the Gallery of Art at Washington University in St. Louis will revisit those years with American Art of the 1980s: Selections From the Broad Collections. The exhibition includes 14 large-scale paintings and sculptures by 11 celebrated and sometimes controversial artists, including Jean-Michel Basquiat, Ross Bleckner, Eric Fischl, Jack Goldstein, Keith Haring, Jeff Koons, Sherrie Levine, Robert Longo, David Salle, Julian Schnabel and Mark Tansey.

American Art of the 1980s opens with a reception from 5:30 to 8 p.m. Friday, Jan. 23, in the Gallery of Art and remains on view through April 18. Gallery hours are 10 a.m. to 4:30 p.m. Tuesdays through Thursdays; 10 a.m. to 8 p.m. Fridays; and noon to 4:30 p.m. weekends. (The Gallery of Art is closed Mondays.) The exhibit is free and open to the public. The Gallery of Art is located in Steinberg Hall, near the intersection of Skinker and Forsyth boulevards. For more information, call (314) 935-4523.

“Over the last four decades, Eli and Edythe Broad have built one of the world’s most important collections of modern and contemporary art, including works by some of our provocative artists,” said Mark S. Weil, Ph.D., the E. Desmond Lee Professor for Collaboration in the Arts and director of the Gallery of Art. “American Art of the 1980s presents a rare opportunity to explore themes and trends not otherwise available in St. Louis public collections.”

American Art of the 1980s

“The decade of the 1980s is characterized by the coexistence of a diverse range of artistic practices,” said Sabine M. Eckmann, Ph.D., curator of the Gallery of Art. “Taken together, these different positions demonstrate the complete arrival of the postmodern in the art world.”

In the1970s, Eckmann explained, artists challenged the primacy of traditional forms such as painting and sculpture, emphasizing instead the “anti-aesthetics” of conceptual art, process art and earth art. By the early 1980s, however, neo-expressionists such as Basquiat, Schnabel and Salle had returned figurative art to the aesthetic fray while injecting a new sense of ironic detachment — appropriating, rather than inhabiting, “authentic” painterly strategies.

For example, Basquiat’s Untitled (Skull) (1981) is at once a strikingly expressive semi-self portrait and a skillful catalog of painterly devices. Salle’s Pound Notes (1986) is a pastiche of found imagery that nevertheless suggests a dramatic, if fractured, narrative. Schnabel’s massive Self-Portrait in Andy’s Shadow (1987), painted on the artist’s signature broken plates and crockery, offers nostalgic and ironic self-presentation while paying homage to cooly sardonic Andy Warhol, whose date-of-death is inscribed on the painting’s surface.

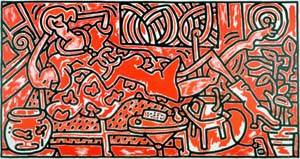

Other major paintings on view include Longo’s iconic Untitled (White Riot Series) (1982), Tansey’s deadpan Four Forbidden Senses (Taste, Sound, Smell, Touch) (1982) and Haring’s massive Red Room (1988).

“Due to their figurative nature, these works appear easily accessible, yet in fact address the dilemma of establishing fixed meaning in the postmodern era,” Eckmann said. “They provoke us to reconsider the position, capacity and role of figuration at the end of the 20th century.”

Appropriation was also central to the work of Levine, whose wry “re-creations” of works by other artists are here represented by Untitled (After Duchamp: Chessboards) #4 (1989). Similarly, Koons’ ornate stainless steel busts Italian Woman and Louis XIV (both 1986) echo art historical precedent while also skewering received standards of “good taste.”

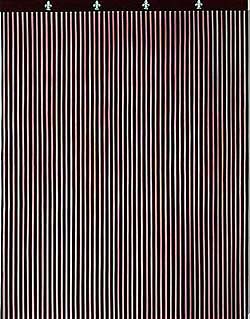

Abstract painting too grew increasingly subversive. Bleckner’s glowing Brothers’ Sword (1986) suggests a sense of almost religious transcendence, yet also is a political statement of support for AIDS victims. The violent, colorful burst of Goldstein’s Untitled (1988) recalls the spontaneity of abstract expressionism, yet its cool tone and glossy sheen slyly reveal the painting’s photographic inspiration.

“In order to engage with these artworks, we may best understand them as postmodern allegories reflecting a fragmented and compartmentalized world,” Eckmann concluded. “These utterly ambivalent artworks address various strands of modernist art — figurative painting, high art, the spectacle — in order to question and ultimately bury those approaches.”

Eli and Edythe Broad

Eli and Edythe Broad have been listed among the top art collectors in the world by ArtNews and Art and Antiques magazines. Since the early 1960s, they have built a personal collection of more than 400 modern and contemporary works, while The Broad Art Foundation, which they founded in Santa Monica, Calif., in 1984, has amassed more than 750 artworks by more than 100 artists.

Eli Broad has been an important patron and board member at more than 25 major museums and art institutions, including the Museum of Modern Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art and the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, all in New York; The Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA); and the Archives of American Art of The Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.

As founding chairman of The Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles, Broad secured the initial acquisitions of the permanent collection, recruited the first two directors and opened both the renowned temporary facility designed by Frank Gehry (itself now a permanent museum facility) and the main building designed by Arata Isozaki. From 1996 to 1999, he chaired the capital campaign for Gehry’s recently opened Disney Hall in Los Angeles.

Most recently, the Broads pledged $60 million to LACMA to create a new building for contemporary art.