Researchers tracking the ebb and flow of cognitive function in the human brain have discovered surprising differences in the ability of younger and older adults to shut down a brain network normally active during periods of passive daydreaming. The differences, which are especially pronounced in people with dementia, may provide a clear and powerful new method for diagnosing individuals in the very early stages of Alzheimer’s disease.

“In young adults, there are parts of the brain that are very active during a passive free-thinking state, but these areas appear to shut down dramatically or ‘turn off’ when the person is asked to do something,” said Cindy Lustig, research team member and post-doctoral fellow in psychology at Washington University in St. Louis. “Interestingly, older people, especially those with Alzheimer’s disease, don’t show this same kind of brain activity during free-thinking, resting conditions.”

In a study published Nov. 25 in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, Lustig and colleagues detail results of functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) tests conducted on groups of young adults, older adults and adults experiencing early signs of Alzheimer’s-related dementia.

Although fMRI testing is widely used to track regional increases in brain activity during completion of specific mental tasks, such as language, memory or problem solving, this study focuses on what happens in regions that are active when the brain has no particular task at hand, regions that are focal points for a baseline, passive processing mode, one that seems to operate when the mind free to wander and daydream.

“What we found in our study is that rather than turning these regions off when asked to concentrate, as young adults do, people with Alzheimer’s seem to turn them on,” Lustig said. “This might reflect a ‘broken brain’ in Alzheimer’s, making it hard for people to turn these brain regions on or off appropriately; more optimistically, it might be an attempt to compensate for the memory problems that come with Alzheimer’s.”

Other members of the Washington University in St. Louis / Howard Hughes Medical Institute research team include Abraham Z. Snyder, Mehul Bhakta, Katherine O’Brien, Mark McAvoy, Marcus E. Raichle, John C. Morris and Randy L. Buckner, all of whom are affiliated with the departments of psychology in Arts and Sciences and/or the departments of neurology and radiology in the School of Medicine.

Raichle, a pioneer in the use of positron emission tomography (PET) to image changes in brain activity, has been an advocate for more research into brain deactivations, a process by which the brain reduces activity in one region so that resources can be shifted to other areas where more challenging mental tasks are currently being processed. Irregularities in brain deactivation patterns have been noted in other neurological illnesses, including amnesia, schizophrenia and Fragile X syndrome.

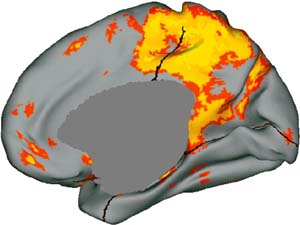

Recent research has provided mounting evidence supporting the existence within the brain of a “default network,” a set of interconnected brain areas that carry out routine, passive mental processes, such as monitoring the environment, registering internal emotions and other forms of largely undirected thought and reflection. Brain areas thought to be included in this network are the medial frontal, the lateral parietal and the posterior cingulate regions of the cortex.

“The posterior cingulate cortex was the site of the largest and most intriguing differences between the groups,” Buckner said. “Whereas young adults showed decreases in this region after a transient initial activation, Alzheimer’s participants maintained an above-baseline activation throughout the task period.”

The study also identified a number of other significant differences in the timing and magnitude of changes in default network activity among young adults, older adults and older adults with early stages of Alzheimer’s.

Other studies have shown that young adults have more activity in this default network than do older adults during so-called passive conditions where they are not given any particular task to think about. What this new study found is that older adults also do not seem to shut down or “deactivate” the default network as much when they are given something to concentrate on.

“The reduced deactivation in the older adult groups are especially surprising, given that the performance data suggested that they found the task more difficult than did the young adults, ” Buckner noted. “In young adults, greater task difficulty is usually associated with greater deactivation in these areas.”

Interestingly, there is one situation in which young adults exhibit some activity in the default or daydreaming regions even while they are actively tackling a mental task elsewhere in the brain; that is when the task at hand involves a person’s autobiographical memory. For instance, if someone asks what you had for breakfast or how you feel about something that happened in your past, then you might activate parts of the default passive processing network as you search for the answer.

“Since the brain’s default processing network is connected to brain areas that are heavily involved with memory, it could be that people with memory problems are turning the network on in an attempt to compensate for the memory damage caused by normal aging or Alzheimer’s,” Lustig said.

“The biggest, most obvious thing that we know about these default regions is that older adults, especially those with Alzheimer’s, are doing something different with them when they’re in a free-thinking mode. The reasons for this aren’t entirely clear, but may have something to do with their memory problems.

“In the long run, this quirk may help us understand what’s going wrong with fundamental cognitive processes that underlie mental declines associated with aging and Alzheimer’s. In the meantime, we’re very interested in whether these changes can be used to identify older adults in the earliest stages of Alzheimer’s disease so that they can begin treatment as soon as possible.”