In high school, John M. Lasala learned the most pivotal and enduring lesson of his life: Persistence and dedication are the keys to success.

LeRoy Vaughn, Lasala’s football coach and chemistry teacher — not to mention father of New York Mets first baseman Mo Vaughn — taught his undersized team to capitalize on its strengths and improve upon its weaknesses.

“He basically taught us common sense,” Lasala recalls. “Through him, I learned that laying out a plan and working hard to stick to it can bring tremendous rewards, even for people who have obvious shortcomings.”

Like LeRoy Vaughn, Lasala’s two main childhood interests were sports and science. He dreamed of becoming a professional baseball player and played semi-professionally through college.

Although still an avid fan and a regular at the local batting cage, he ultimately realized his strengths and talents were better suited to the laboratory and clinic, not the ballpark.

But the lessons he learned from Vaughn have guided him through his sometimes circuitous but always successful career path. And his perseverance has paid off.

Lasala, M.D., Ph.D., is medical director of the cardiac catheterization laboratory and associate professor of medicine in the School of Medicine and director of interventional cardiology at Barnes-Jewish Hospital. In these roles, he has the opportunity to combine his passions for biochemistry and patient care to help shape the relatively new and burgeoning field of interventional cardiology.

“John has revolutionized the catheterization laboratory and interventional cardiology program at Washington University and Barnes-Jewish Hospital,” says Alan C. Braverman, M.D., professor of medicine and director of the University’s Marfan Syndrome Clinic.

“John has brought the latest procedures and interventions to our campus and has assembled a highly skilled group of interventional cardiologists. He is an innovative interventional cardiologist and has made our center a high- volume, world-class operation.”

Healing hands

In addition to being a second-generation Italian-American, Lasala hails from a family of artisans, from his mother who is a dress designer in New York City to his three musician aunts.

But even as a 4-year-old, Lasala would sit on the stoop of his family’s urban Connecticut apartment building and volunteer to bandage his neighbors’ cuts and bruises.

“You could tell I was different from the beginning,” he laughs. “My parents were always very supportive, but they knew little about the field I was interested in.”

But he still inherited a love for working with his hands and spent hours playing with chemistry sets.

He later majored in chemistry and minored in biology as an undergraduate at Drew University. He combined the two as a biochemistry Ph.D. student at Saint Louis University.

“Doing experiments always really stimulated my imagination,” he says. “I enjoyed the intellectual process and became fascinated with how to answer important questions from a biological standpoint.”

As a postdoctoral fellow in anatomy and neurobiology at Washington University, Lasala used his aptitude for biochemical experimentation to study human disease. But he quickly realized that becoming an academic scientist would mean more time behind a desk than in the laboratory.

So he returned to the East Coast to earn a medical degree at the University of Connecticut, where he rediscovered his passion for patient care and, in particular, for cardiology.

Matters of the heart

As he fluctuated between basic research and clinical medicine, Lasala could not have predicted how the two would ultimately merge to help him lead the young field of interventional cardiology.

When he returned to St. Louis for an internship and residency at Barnes-Jewish Hospital, he was overwhelmed by the draining lifestyle of being a cardiologist at a top-rated institution. So when Yale University School of Medicine recruited him to establish a basic research laboratory, he agreed.

It was there he became enchanted by interventional cardiology, a subspecialty then just being developed.

For the first time, a small group of cardiologists around the country was beginning to address the possibility that serious heart conditions such as heart attacks could be treated without open-heart surgery. It was an exciting and fascinating new area of medicine for Lasala — and a unique opportunity to simultaneously make significant clinical and research contributions.

His mentors at Yale desperately tried to convince him otherwise, arguing that his talents and sophisticated basic science background would be better served researching biochemistry than treating the heart by predominantly mechanic means.

But Lasala had foresight: He envisioned that the field of interventional cardiology would allow researchers like himself to apply biological insight to treat mechanical problems.

He was right. With the advent of interventional cardiology, millions of patients have avoided heart surgery by instead being treated with metal mesh tubes called stents, routinely used as scaffolding to keep blood vessels open.

One of the most promising advancements is a marriage between Lasala’s two areas of expertise: The use of drugs to coat stents and further prevent reclogging applies biochemical principles to improve coronary care.

“I was there when the first coronary stents were placed, and the results literally sent a shiver up my spine,” he recalls. “It is absolutely astounding how much progress we’ve made in the last decade.

|

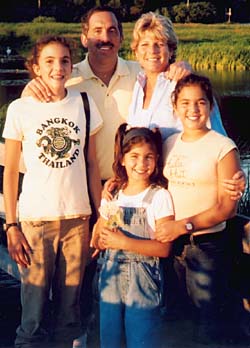

John M. Lasala Titles: Medical director of the cardiac catheterization laboratory and associate professor of medicine in the School of Medicine; director of interventional cardiology at Barnes-Jewish Hospital Family: Wife, Carolyn; daughters Stephanie, 14, Erica, 12, and Olivia, 8 Hobbies: Sports and music — he used to play guitar and sing in a band years ago. “I was the original ‘wedding singer,'” he jokes. |

“Early results with drug-coated stents are almost too good to be true and may be the most important advancement in cardiology this decade.”

Having established the medical school’s now renowned interventional cardiology clinical service and fellowship training program, Lasala continues to combine his knack for both biochemistry and cardiology to help lead efforts to develop and improve clinical innovations such as coated stents.

“There’s nothing more gratifying than to watch people actually get better,” he says, “and in cardiology, you have the chance to make a huge impact on patients.”

According to Craig K. Reiss, M.D., associate professor of medicine and director of Washington University Cardiology Consultants, Lasala’s commitment to patient care is extraordinary, particularly because interventional cardiologists do not typically need to follow patients over time.

Reiss’ father, a former patient of Lasala’s, insisted that Lasala be involved in his medical care even when his condition extended beyond the scope of cardiology.

“John never settles for anything except doing the best possible job for his patients,” Reiss says. “He has unbelievable judgment regarding the appropriateness of procedures for his patients and provides them with tremendous personal care, often maintaining long-term relationships with them.”

Lasala feels charmed by what his life has become. Perseverance and the ability to optimize his strengths, as Vaughn taught him several decades ago, allow him to balance a rewarding academic and clinical career with an equally satisfying personal life.

Going to the batting cages, watching sports and spending time with all the females in his life — his wife, three daughters, two female dogs and two guinea pigs — allows him to deal with the rigors of his career.

“I feel blessed to have fallen into a position that allows me to satisfy all of my interests while still having time to spend with my family,” Lasala says. “If I died tomorrow, I would feel relatively satisfied because I’ve been a part of this tremendous treatment revolution in coronary disease and, more recently, in other cardiovascular entities.”

John M. Lasala, M.D., Ph.D., associate professor of medicine, talks with a patient before his procedure in the cardiac catheterization laboratory, which he directs. “John never settles for anything except doing the best possible job for his patients,” says Craig K. Reiss, M.D., associate professor of medicine.