Recurring tonsil infections and sore throats are a fact of life for many children. The pediatrician prescribes antibiotics, and they help for a while, but the infection returns. The pattern repeats itself until the doctor — or the frustrated parents — finally decide that the wrinkly olive-sized ovals of inflamed tonsil tissue must come out. Why, they wonder, can’t the body eliminate these infections, even with the help of antibiotics?

Researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis may have found the answer. They discovered that bacteria often form biofilms in the wet and warm folds of the tonsils, and that these may serve as reservoirs of infection. The findings are published in the June 2003 issue of the Archives of Otolaryngology: Head and Neck Surgery.

“We’ve been removing tonsils for a century, usually out of desperation, when these nasty chronic infections persist,” says principal investigator Richard A. Chole, M.D., Ph.D., Lindburg Professor and head of the Department of Otolaryngology at the School of Medicine. “Our findings suggest that these infections may not respond to treatment because the bacteria form biofilms that protect them from antibiotics and the immune system.”

Biofilms are organized colonies of bacteria. Recent evidence has linked biofilms to a variety of persistent infections including dental plaque, cystic fibrosis, urinary tract infections, ostoemyelitis and ear infections. Some studies have shown that bacteria in biofilms may be 5,000 times more resistant to antibiotics than the same free-swimming bacteria.

Infection of the tonsils, or tonsillitis, is one of the most common infectious diseases of childhood. Recurrent tonsillitis generally is treated by removing the tonsils, a procedure known as tonsillectomy. More than 400,000 tonsillectomies are performed annually in the U.S., making it one of the most common surgical procedures involving children.

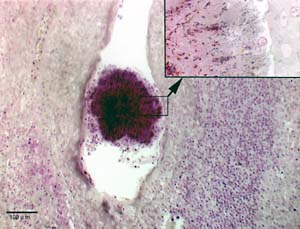

Chole and co-author Brian T. Faddis, Ph.D., assistant professor otolaryngology, used light and electron microscopes to examine tonsils removed from 19 patients for evidence of biofilms. Fifteen sets of tonsils were removed because of repeated infections; four were uninfected and removed because they were enlarged and obstructing the throat.

Eleven of the 15 infected sets of tonsils showed signs of biofilms, as did three of the four pairs of enlarged tonsils.

“Some of the biofilms were large enough to see with the naked eye,” Chole says. “We used to think these films were collections of cell debris and sloughed off tissue. Now we know they are loaded with bacteria in a biofilm matrix.”

Bacteria form biofilms after first adhering to a surface inside the body. They then secrete sugar-like materials that form a matrix around them and send out chemical signals to tell other nearby bacteria that biofilm formation is in progress.

Research by others has shown that six to nine different species of bacteria may reside in the same tonsillar biofilms.

“The presence of mixed bacterial biofilms may further explain why tonsillar infections can resist antibiotic therapy,” Chole says.

To their surprise, the investigators also found biofilms associated with three of four tonsils removed because they were enlarged. These tonsils were not infected.

“This may suggest that some interaction with biofilms in the tonsils is necessary for normal health and development,” Chole says. “Perhaps this is one way that the body develops immunity to bacteria in the outside world.”

If this were true, he explained, it would mean that caution is necessary when developing drugs designed to attack bacteria in biofilms.

Currently, Chole is studying the role of biofilms in cholesteatomas, middle-ear infections that can lead to deafness.

___________________________________________________________

Chole RA, Faddis BT. Anatomical evidence of microbial biofilms in tonsillar tissues: a possible mechanism to explain chronicity. Archives of Otolaryngology and Head and Neck Surgery, 129, 634-636, June 2003.

Funding from the National Institute on Deafness and Other Communication Disorders supported this research.