Neuroscience researchers at Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis are studying the brains of patients with Tourette Syndrome (TS) to see whether they can identify differences in the dopamine system in people with the tics that characterize TS. The researchers have received a grant from the Tourette Syndrome Association to use positron emission tomography (PET) imaging to compare dopamine release and uptake in the brains of TS patients to people without the syndrome to learn how that important neurotransmitter functions differently in TS.

Movies, television shows and other popular media presentations tend to portray people with TS as whooping, shuddering and cursing uncontrollably, but the syndrome often is much more subtle, according to Kevin J. Black, M.D., assistant professor of psychiatry, neurology and radiology at Washington University.

“Imagine you’re in church during a quiet time of prayer or at the symphony during a soft section in a piece of music, and you realize you have to cough,” Black says. “You try not to cough or to stifle the cough, but your body doesn’t want to cooperate. Tourette Syndrome is something like that, except it’s all day, every day.”

Black says many people with TS feel their unwanted movements or tics are not the problem as much as the uncomfortable sensations and urges to move that precede them. Scientists once thought TS was a very severe and rare condition — something a doctor might encounter only once or twice during the course of a career — but now the range of severity involved in TS is understood to be much broader, and scientists like Black have discovered that the number of people with the tics that characterize TS is much greater than previously thought.

“Most people with Tourette Syndrome function entirely normally and have a job and family,” he says. “The severity of symptoms can wax and wane over time. There are some people with very severe symptoms such as involuntary cursing, but that’s only a small minority. It’s much more common for people to say brief fragments of words or to sniff, cough or hum. As far as involuntary movements go, those usually involve simple movements like blinking, head shaking or shoulder shrugging.”

Black and colleagues believe one thing that may be different in people with TS is dopamine. Past research has shown drugs that interfere with dopamine messages in the brain also suppress tics. Interestingly, Black’s research team also has noticed that increasing the brain’s dopamine levels with levodopa — a natural amino acid that has been used for many years to treat movement disorders, such as Parkinson’s disease — also may improve tics.

Originally, they worried that boosting dopamine levels with levodopa might make tics worse, but during the first several minutes after receiving the drug, the researchers noticed improvement in tics instead. Black’s group now is conducting a clinical study to determine whether long-term treatment with levodopa might help people with TS keep their tics under control

The researchers also are using imaging techniques to see what the brain does in response to the levodopa. One study found that treatment with the drug helps people with TS perform certain memory tasks more effectively. Now they want to see whether the brains of people with TS actually make more or less dopamine in response to levodopa or whether the difference might be downstream from dopamine production and instead involve the uptake of dopamine in key brain structures.

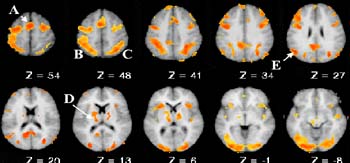

They’ll measure that using PET imaging. Working with Mark Mintun, M.D., professor of radiology and of psychiatry, Black and colleagues will inject people who have TS with a chemical marker, called [11C]raclopride, that sticks to dopamine receptors in the brain. Because the raclopride sticks to the dopamine receptors, if dopamine release is boosted, it pushes the raclopride marker off of receptors. As neuroscientists look at the PET images of the brain, they can see very bright areas that turn increasingly dimmer as dopamine is taken up by receptors and the raclopride marker is pushed out of the way.

“We’re going to give levodopa to volunteers who don’t have Tourette Syndrome to see whether we can measure the boost in the brain’s dopamine levels in response to the levodopa,” Black says. “Then, we’ll do the same thing in people with tics to see whether there’s a difference in the amount of dopamine production, which we’ll measure by looking at raclopride displacement.”

If there are differences in dopamine production, it will demonstrate that something is different in how the brain produces dopamine or how it responds to external signals to produce dopamine in people with TS. If it turns out that dopamine production is normal in TS, the researchers will be able to move forward and look at the parts of the brain where dopamine uptake occurs.

It is clear to Black that the dopamine system is somehow related to TS. What’s unclear is how it might malfunction to cause tics. Black says this study will allow his team to see, for the first time, exactly how the dopamine system changes in TS, and that should provide clues about the best strategies for treatment.