Microbes buy low and sell high

Microbes set up their own markets, comparing bids for commodities, hoarding to obtain a better price, and generally behaving in ways more commonly associated with Wall Street than the microscopic world. This has led an international team of scientists, including two from Washington University in St. Louis, to ask which, if any, market features are specific to cognitive agents.

Odor receptors discovered in lungs

Your nose is not the only organ in your body that can sense cigarette smoke wafting through the air. Scientists at Washington University in St. Louis have shown that your lungs have odor receptors as well. The odor receptors in your lungs are in

the membranes of flask-shaped neuroendocrine cells that dump neurotransmitters and neuropeptides when the receptors are stimulated, perhaps triggering you to cough to rid your body of the offending substance.

Tyson designated an Earth Observatory

A 60-acre plot in Washington University in St. Louis’ Tyson Research Center has been named a Forest Global Earth Observatory, or ForestGEO. The oak-hickory forest in the rolling foothills of the Ozarks joins a network of 51 long-term forest study sites in 23 countries, including eight others in the United States. Together, the forests, containing roughly 8,500 species and 4.5 million individual trees, comprise the largest, systematically studied network of forest-ecology plots in the world.

VIP treatment for jet lag

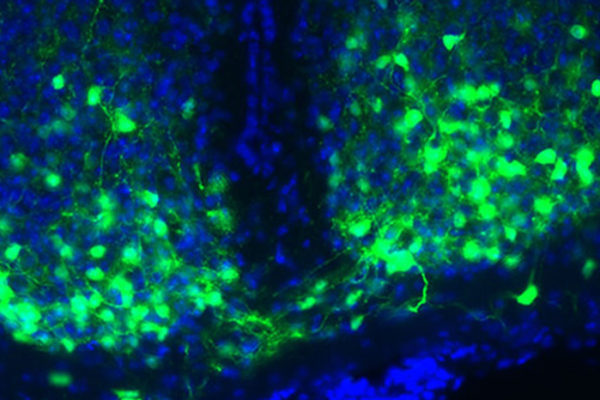

A small molecule called VIP, known to synchronize time-keeping neurons in the brain’s biological clock, has the startling effect of desynchronizing them at higher dosages, says a research team at Washington University in St. Louis. Neurons knocked for a loop by a burst of VIP are better able to re-synchronize to abrupt shifts in the light-dark cycle like those that make jet lag or shift work so miserable.

Ignorance is sometimes bliss

Evolutionary biologist W.D. Hamilton predicted that organisms ought to evolve

the ability to discriminate degrees of kinship so as to refine their ability to direct help to individuals with whom they shared the most genes. But two WUSTL biologists point out that there seem to be many cases where “a veil of ignorance” prevents organisms from gaining this kind of information, forcing them to consider a situation from the perspective of all members of their group instead of solely from their own perspective or that of their close kin.

Model organism gone wild

Some wild clones of social amoebas farm the bacteria they eat, but this is a losing strategy if nonfarming amoebas can steal the farmers’ crops. To make the strategy work, the farmers also carry bacteria that secrete chemicals that poison free riders. The work suggest farming is complex evolutionary adaptation that requires additional strategies, such as recruiting third parties, to effectively defend and privatize the crops, the Washington University in St. Louis scientists say.

Social amoebae travel with a posse

Some social amoebae farm the bacteria they eat. Now a collaboration of scientists at Washington University in St.

Louis and Harvard University has taken a closer look at one lineage, or

clone, of D. discoideum farmer. This farmer carries not one but two strains of bacteria. One strain

is the “seed corn” for a crop of edible bacteria, and the other strain

is a weapon that produces defensive chemicals. The edible bacteria, the scientists found, evolved from the toxic one.

A chance to explore the hottest research topic in St. Louis

The International Society of Photosynthesis

Research, meeting this August in St. Louis, is offering an afternoon of

talks and demonstrations about the original “green” chemistry invented

by bacteria and plants and its relevance to our energy future. Intended for teachers, students and the public, “Photosynthesis in

our Lives” will take place from 3- 5 p.m. the afternoon of Sunday,

August 11, 2013 in the Parkview room at the Hyatt Regency at the Arch. RSVP to: http://parc.wustl.edu/outreachRSVP by August 7, 2013.

How rice twice became a crop and twice became a weed — and what it means for the future

With the help of modern genetic technology and the

resources of the International Rice GeneBank, which contains more than

112,000 different types of rice, evolutionary biologist Kenneth Olsen has been able to look back in time at the double domestication of rice (in Asia and in Africa) and its double “de-domestication” to form two weedy strains. Olsen predicts the introduction of pesticide-resistant rice will drive ever faster adaptation in weedy rice.

The Swiss Army knife of salamanders

WUSTL biologist Alan Templeton and colleagues in Israel and Germany received $2 million to look at the shifting patterns of gene expression, called

the transcriptome, in two remarkably versatile species of fire salamander, one native to Israel and the other to Germany. The work may explain why this genus of salamanders is able to adapt to a wide variety of habitats when most salamander species live in one.

View More Stories