Whenever I teach my course on the American Presidency, I ask students to rate every U.S. president. The last time I did so, nineteen percent considered Jimmy Carter, who died Sunday, Dec. 29, to be a great president. Exactly the same number considered him a bad president. One student considered him the greatest U.S. president. Another considered him forgettable.

No other president generates a spread like this. Why does Jimmy Carter?

My students know that Carter struggled as president and lost his bid for re-election. Yet they also know about his fundamental decency, his deep and abiding religious faith, and the commitment to human rights that informed both his presidency and his post-presidency.

Indeed, my students are at the receiving end of almost a half-century of Americans seeking to make sense of Carter, a process in which Carter himself was an active participant. Two visits Carter made to St. Louis can help us to understand that process.

Throughout the 1960s and early 1970s, the presidents who preceded Carter — John Kennedy, Lyndon Johnson, Richard Nixon, Gerald Ford — extolled their status as insiders. None had held statewide office, and all claimed that extended service in Washington qualified them for the presidency.

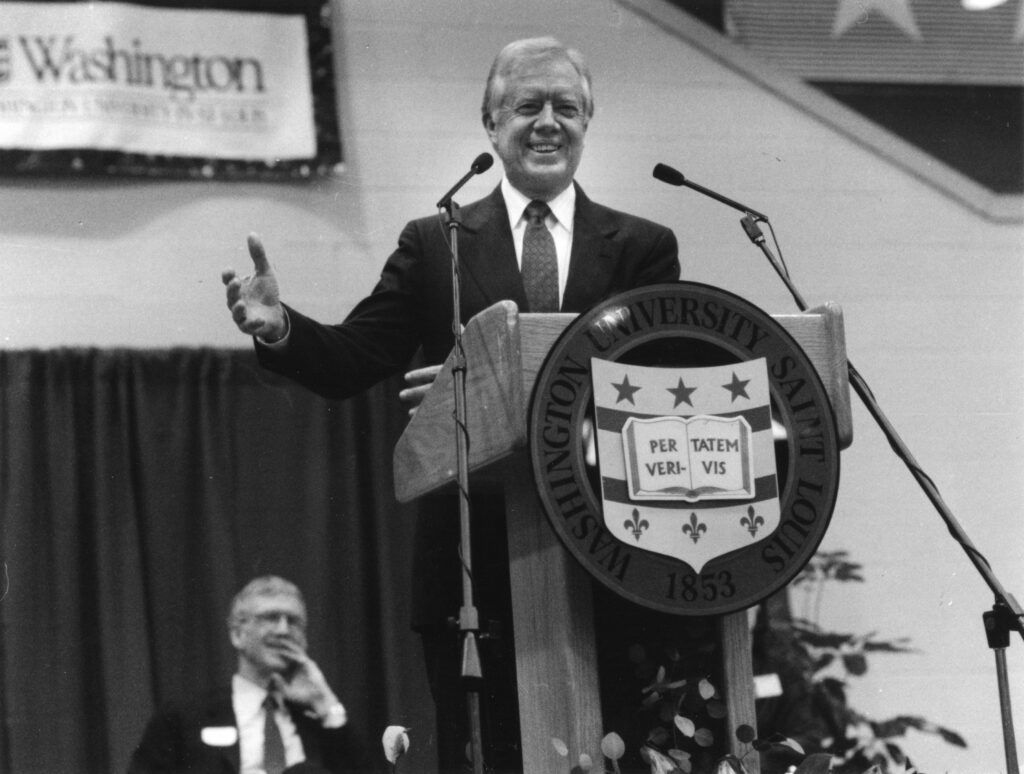

Carter saw politics differently, and always with a perceptive eye toward where American sentiment was moving. When he first spoke at Washington University, in 1975, he was an unknown factor, and made the case that his very unfamiliarity made him an ideal candidate. Indeed, that would become the theme of Carter’s presidential campaign. He ran as a self-proclaimed outsider, a southern governor who made a virtue of never having served in Washington.

This outlook served him well in 1976, but in 1980 he was outdone by the competing outsider campaign of Ronald Reagan. And in the decades since, a set of wildly different presidential candidates — Bill Clinton and George Bush, John McCain and Barack Obama, and most recently Donald Trump — have all claimed Carter’s outsider mantle.

Carter left office in 1981 but he never fully left the public eye. In this, Carter took a page from the playbook of none other than Richard Nixon. After the disgrace of Watergate and resignation, Nixon pursued a relentless campaign of public rehabilitation. He did so primarily through speaking and writing about foreign policy, casting himself as a wise elder statesman.

This was a far cry from Carter’s focus on human rights, which ranged from building the Carter Center to volunteering for Habitat for Humanity to serving as an occasional negotiator in world hotspots. Yet unlike so many former presidents of their era, Nixon and Carter both left office convinced they had something to prove. And both believed they could quite literally rewrite the way people thought of them, producing not only conventional memoirs but also entire libraries on politics, diplomacy, and their visions for the nation.

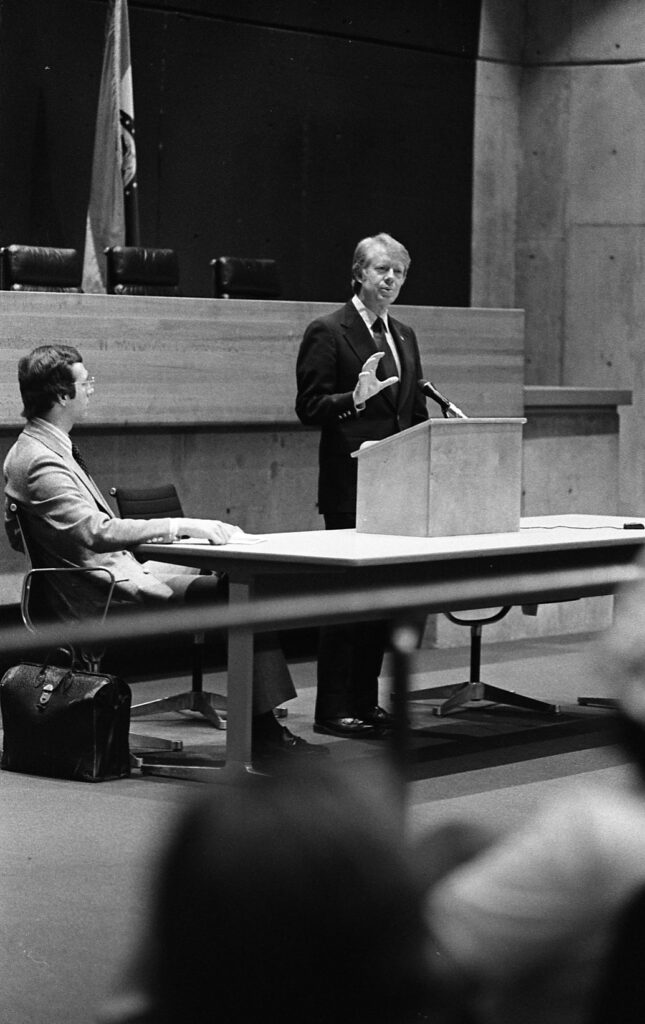

When Carter returned to WashU, in 1991, it was at the height of his second act. His remarks explored how a personal ethic of empathy and service could inform both politics and citizenship. He called on students to pursue a life that was “unpredictable and adventurous. That is what will determine the excellence of our lives…What we are able to share with others and make their lives free of suffering and let them enjoy the liberty and the gratification, the security, that we enjoy. So in helping others, we help ourselves.”

In many ways, Carter was like other American presidents: personally ambitious and impatient to achieve his agenda; combative with political opponents during his time in office and occasionally prickly with his successors in the White House. And yet two generations of Americans knew Carter very differently, as man of modesty and service, thoughtful writing and general good humor.

Carter left office long before any of my current students were born and yet many share a personal affection for him. That is no easy accomplishment for a president who served only one term and did so (from their perspective) so long ago. That affection, as much as his presidency, stands as a testament both to who Carter was as a person and to how he reimagined politics for the nation and for the world.

Peter Kastor is the Samuel K. Eddy Professor of history and American culture studies in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis.