It started out as a joke. Suzan-Lori Parks — the Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright and MacArthur “genius award” recipient — tells us that she was just messing around one day, boasting to a friend that, in her next play, she was going to adapt Nathaniel Hawthorne’s classic American novel “The Scarlet Letter” and call it “Fucking A.”

The “A” in Hawthorne’s novel, as dutiful English majors will recall, is “adultery.” It tells the story of Hester Prynne, an unmarried woman in Puritan New England who is scorned by her moralistic community for an affair that results in the birth of a so-called bastard child.

In Parks’ play, however, the “A” stands for “abortion,” and her Hester is not a white Puritan but a Black abortionist. Like her namesake in Hawthorne’s novel, Parks’ Hester wears a scarlet “A” on her chest; but where Hawthorne’s character wears a letter stitched on her clothes, Parks’ Hester has been branded and her suppurating wound refuses to heal. As this suggests, Parks’ joke turns deadly serious in her dramatic treatment of this pun. Refusing to heal, Hester’s branded “A” is both a wound of the flesh, attesting to the materiality of the body, and an abstract symbol. And we, the audience, must understand it as both literal and metaphorical at the same time.

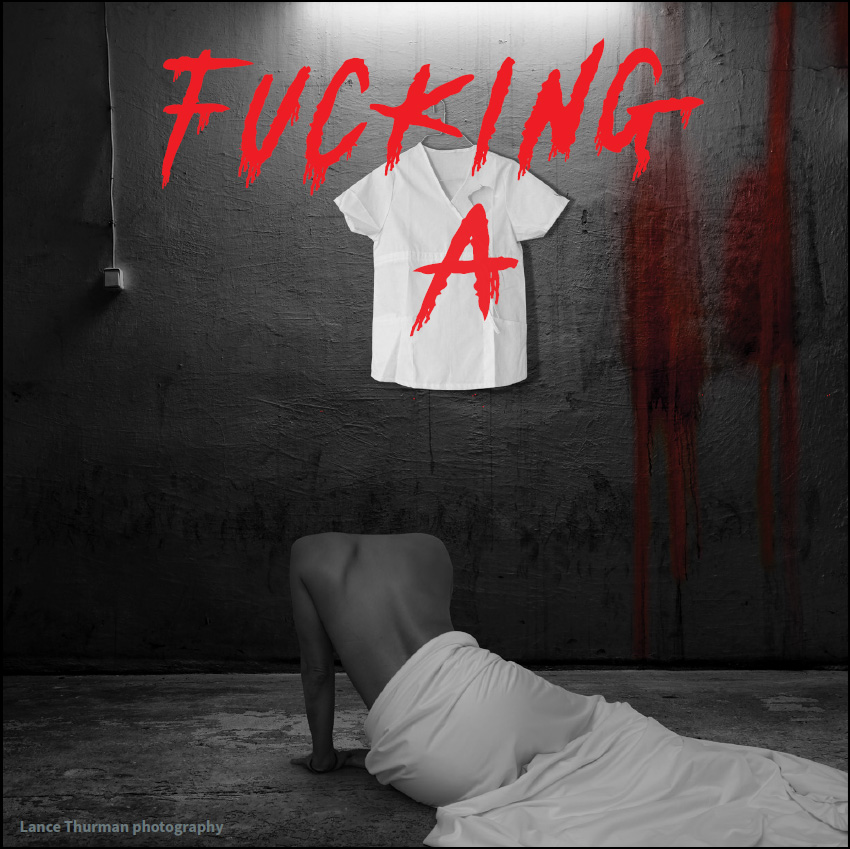

This is how theater works. And this is the challenge that audiences will face when the Performing Arts Department’s production of the play opens Thursday, April 20, in the Hotchner Studio Theatre. At its best: theater asks us to frame a single idea in two ways simultaneously. The scar on Hester’s chest testifies to the brutality suffered by Black bodies enslaved in the Antebellum South and again after Reconstruction in lynchings throughout the United States. Parks refers to both historical eras at the same time, sometimes to dizzying effect. But the “Great Hole of History” into which Black lives have been lost is a vortex that always opens out to the here and now. We, like the characters in “Fucking A,” often have trouble making sense of the past and so, as George Santayana predicted, stand condemned to repeat it.

But if the “A” represents abortion as both a material fact within the world of the play and a symbol outside of it, then what does it symbolize? Unsurprisingly, the play offers a complex answer. Given the history of slavery and its social legacy that Parks treats throughout the play, it is at once a symbol of an aborted future of freedom and personhood, on the one hand, and the psychological toll of racism and the “social death” it imposes on a people whose humanity is denied, on the other. These ideas are sketched out in several plot details. Hester’s son, Boy, has been imprisoned for a crime vaguely described as a “theft” (which historically resonates with the false charge of rape by his white woman accuser). Meanwhile, the prison system profits from Hester’s desire to reunite with the son who was taken from her (historically resonating again with the domestic slave trade).

Insofar as it marks her abjection, Hester’s “A” also functions a symbol of racism itself. She and her friend Canary (“a kept woman”) each perform “one of those disrespectable but most necessary services.” They are, in effect, what historian Yuri Slezkine calls “Mercurians” in his comparative study of historical racisms: Jews who made interest-bearing loans in early modern Christian Europe, Africans impressed into grueling labor on plantations throughout the Black Atlantic, Dalits relegated to sanitation work in India, etc. The bell of history tolls throughout its centuries of ghettoes and work camps. Hester has been given the choice to either go to prison or become an abortionist, but she knows how the economy works: In prison she can’t buy Boy’s freedom, so she assumes her bloody profession.

Hester also labors within the sex-gender system. In Parks’s plays—as in Henrik Ibsen’s—there are always two economies at work: one is explicitly financial, the other implicitly sexual. As a woman in a patriarchal society, Hester is caught in both. Canary stands at their intersection. And First Lady, the seemingly barren wife of the Governor, who sent Boy to jail with a flick of her wrist, does, too. Targeted for assassination by her husband who seeks her inheritance, she flees. Into the arms of Boy, who — recently escaped — shares her longing for sexual fulfillment. Their union takes place offstage, but, even in its ambiguity, it reframes that earlier charge of “theft” as an illicit — because interracial — act of desire. As slave catchers leap through the “Great Hole of History” to appear as bounty hunters in pursuit of Boy, the play hurtles toward its tragic conclusion.

But there is at least one more abortion for Hester to perform. As she takes vengeance on the woman responsible for her son’s fate by denying the Governor an heir, she also ends her own family line and, with it, the possibility of an interracial — or indeed any kind of — future.

First produced in 2000, Parks’ play was conceived, so to speak, in the middle of Roe v. Wade’s 50-year term as stare decisis, or legal precedent. The prospect of the Supreme Court’s recent decision to overturn Roe was likely not on Parks’ mind at the time. But it will be on ours now, in 2023, as we engage the play in performance. What are we to make of its use of “abortion” as both a material fact and a symbolic trope? Parks doesn’t offer easy answers. Described as a “baby killer,” Hester is also unable to secure the “freedom” of her own or her son’s bodies.

In a society where one may be marked as abject yet necessary to the functioning of society, Hester is both Black and a woman. And we are left to reflect on it all.

Julia Walker is chair of the Performing Arts Department and professor of English and of drama, all in Arts & Sciences, at Washington University in St. Louis. Suzan-Lori Parks’ “Fucking A” is produced by PAD guest director Jacqueline Thompson. It will be performed in WashU’s Hotchner Studio Theatre April 20-23.