Sculptor Ted Aub, BFA ’77, completed his first major work, Dancing Graces, as a WashU undergraduate, opening the door to a lifetime of art and teaching. Now, almost 50 years later, he’s putting the finishing touches on a remarkable career.

Aub entered what was then known as the School of Art in 1973 as a painting student, yet the emergence of sculpture as his primary medium of expression began long before. Growing up in Cincinnati, Ohio, Aub remembers poring over his grandmother’s book on Rodin as a child. In grade school, when assigned to write historical essays, he bargained with his teachers to instead produce portrait busts characterizing historical figures, such as Abraham Lincoln and Julius Caesar. He even went as far as creating a sculpture of Zeus on Mount Olympus to substitute for an essay on Greek mythology.

“I got away with it, but it was fair,” Aub says. “I probably did much more work than those adapting text from an encyclopedia. That was a start.”

While Aub’s fascination with the human form’s infinite modes of expression led him to major in painting at WashU, it was a series of elective classroom experiences that shaped his love for sculpture into an enduring ambition. He cites the teaching of sculptor and professor Richard Duhme (perhaps most familiar for his bronze sculpture Fighting Bears that stands near the Athletic Complex). “He had a very academic approach — straight observation, figure studies,” Aub says. “I loved it.”

But Duhme went on sabbatical during Aub’s senior year, and a younger instructor filling in challenged students to represent a model in different ways. “He just blew it wide open and said you can do whatever you want,” Aub recalls.

This is when Aub began creating Dancing Graces, a sculpture that would both redirect his interests and expand his creative limits. “I didn’t know what I was getting into,” he says of the semester-long effort. “It was very difficult to mold and to cast, even in plaster.”

Dancing Graces presented three intertwined figures — or perhaps one at different points in time — the first with arms folded in, the second opening up, and the third with arms open, conveying motion and the flowering of expression. In retrospect, Dancing Graces also provided a metaphor for a career that was unfolding at that very moment.

After WashU, Aub attended the Brooklyn Museum Arts School as a Max Beckmann Scholar and earned an MFA in sculpture from Brooklyn College in 1981. That same year, he began teaching at Hobart and William Smith Colleges in Geneva, New York, where he served 45 years as a professor of art and architecture, until his retirement this year.

But before that, as part of his education in Brooklyn, Aub spent a year studying marble carving in the Tuscan town of Pietrasanta. “That beautiful, sleepy town was a mecca for sculptors,” Aub says, recalling stone carvers but also bronze casters and a number of foundries. There, Aub became proficient in the ancient lost-wax casting technique, perfected by the ancient Greeks, which involved alternating positive and negative impressions in clay, plaster, wax and ultimately, in multiple bronze sections that are welded together into a finished work. This inspiration led Aub and his wife, who also teaches art at Hobart and William Smith Colleges, to buy a peaceful villa in Pietrasanta, where to this day they both live part time and keep additional studios.

Forging a unique career

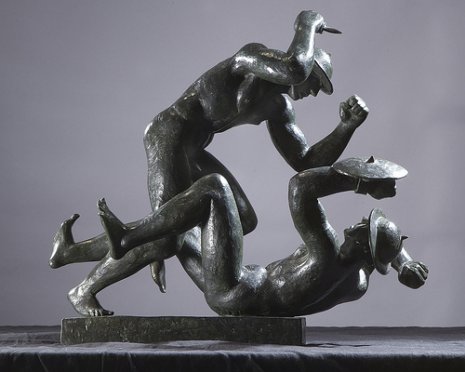

Across six decades of sculpting, Aub found himself fascinated with dualities in his work, often echoing his life’s pursuits — painting and sculpture; teaching and making; history and modernity; and movement and stasis. His 1992 sculpture Tete a Tete depicts two identical figures that present an amusing symmetry when displayed next to each other and yet, when interjoined, represent a struggle, perhaps with the self (Aub notes the similarity of “Tete” to “Ted” in the title). Aub alternates displaying the figures side by side or locked in conflict, each time linking them in his own playful and poetic way. His 2004 sculpture Amore RomA features two similarly posed Roman warriors fighting — one with a dagger, the other a shield. The stark contrast between offense and defense is designed to evoke a variety of human and even political connotations.

Throughout his career Aub also found ways to reconcile his artistic passions — sculpture and painting — within his work. In the mid-’90s, he was commissioned to create a sculpture commemorating the meeting of Elizabeth Cady Stanton (who led the first women’s rights convention in Seneca Falls, New York, in 1848) and Susan B. Anthony, both of whom would work together on women’s rights advocacy in the latter 19th century.

Determined to make his sculpture more than a photo opp, Aub’s vision was to have Stanton, whose work preceded Anthony’s by several years, standing in a resting pose, while Anthony approached her, both ready to shake hands. But rather than depict the handshake itself, Aub depicts the anticipatory moment just before, drawing inspiration from Michelangelo’s Creation of Man painting in the Sistine Chapel — where the hands of God and Adam are slightly apart — adding a touch of the divine to the two leaders’ first meeting and evoking the possibilities for their collaboration ahead.

Full circle

Aub’s recent work has focused on bringing figures from famous paintings directly into sculptural form. But last year, as he contemplated retirement, Aub realized there was something keeping him from fully realizing his artistic vision. To close the gap between past and present, he decided to revisit 1977’s Dancing Graces, which he had so painstakingly cast in plaster all those years ago at WashU.

“The piece wasn’t aging well, so to preserve it properly I made the casting in bronze — in over 30 parts and weighing 200 pounds,” Aub says. “It’s unusual to have a casting in that many pieces in one sculpture, but I had thought long and hard about how I’d change it. It was a work from back when I was a young kid basically.”

Aub refined certain parts of Dancing Graces (arms, fingers, toes) that felt clumsy or heavy in that first attempt. And, earlier this year, he assembled those parts, welding each together into a final version, ultimately 50 years in the making. “Now it has a richer surface and more of an overall lightness,” he says. “It works better, and I’m so much happier.”

“You think about the time you have left, what you’ve done and haven’t done.”

Ted Aub

Today, Aub’s artistic pursuits have come full circle. To honor his retirement, Hobart and William Smith will hold a career-spanning exhibition of his sculptures taking place January 29–February 21, 2026, in its Davis Gallery in Geneva, New York, for which Aub is importing crates of sculptures back from Italy. At 70, Aub is also reflecting on his future. “You maybe have 10 years or more,” he says. “You think about the time you have left, what you’ve done and haven’t done.”

With all the closure this year provided, one thing remains constant: Aub will always be a sculptor at heart, ready for his next commission and his next big idea, eager to forge ahead.