More than half a century after the U.S. government deemed psychedelic drugs to be of “no medical use,” scientists have begun re-evaluating that dismissive assessment with the tools of modern science. Dozens of clinical trials of psychedelic-assisted therapies for depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and other conditions are underway or planned. So far, the results largely verify what Indigenous peoples with cultural traditions of psychedelic use have long known: Psychedelics are best treated not as party drugs but as potent medicines that can provide unique healing benefits when used appropriately.

Even as evidence grows of the drugs’ medicinal uses, however, little is known about how they work, or how best to harness their power in a way that benefits the people who need it most. As national leaders in neuroscience and implementation science, WashU Medicine researchers are poised to help solve these puzzles and transform psychedelics into safe, effective and accessible therapies for some of the most challenging conditions.

“Psychedelic drugs have enormous potential to help people whom we can’t currently help, but the only way to turn that potential into reality is to conduct scientific research.”

Ginger Nicol, MD

“We desperately need new approaches to treating mental health disorders,” says Ginger Nicol, MD, an associate professor of psychiatry at WashU Medicine. “The therapies we have do some good, but not enough. For PTSD, for example, our best therapies help only about a third of patients, which is tragic because PTSD causes enormous suffering. It literally kills people.

“Psychedelic-assisted therapy is something people want. They are already self-medicating, which can be really dangerous,” Nicol adds. “Psychedelic drugs have enormous potential to help people whom we can’t currently help, but the only way to turn that potential into reality is to conduct scientific research.”

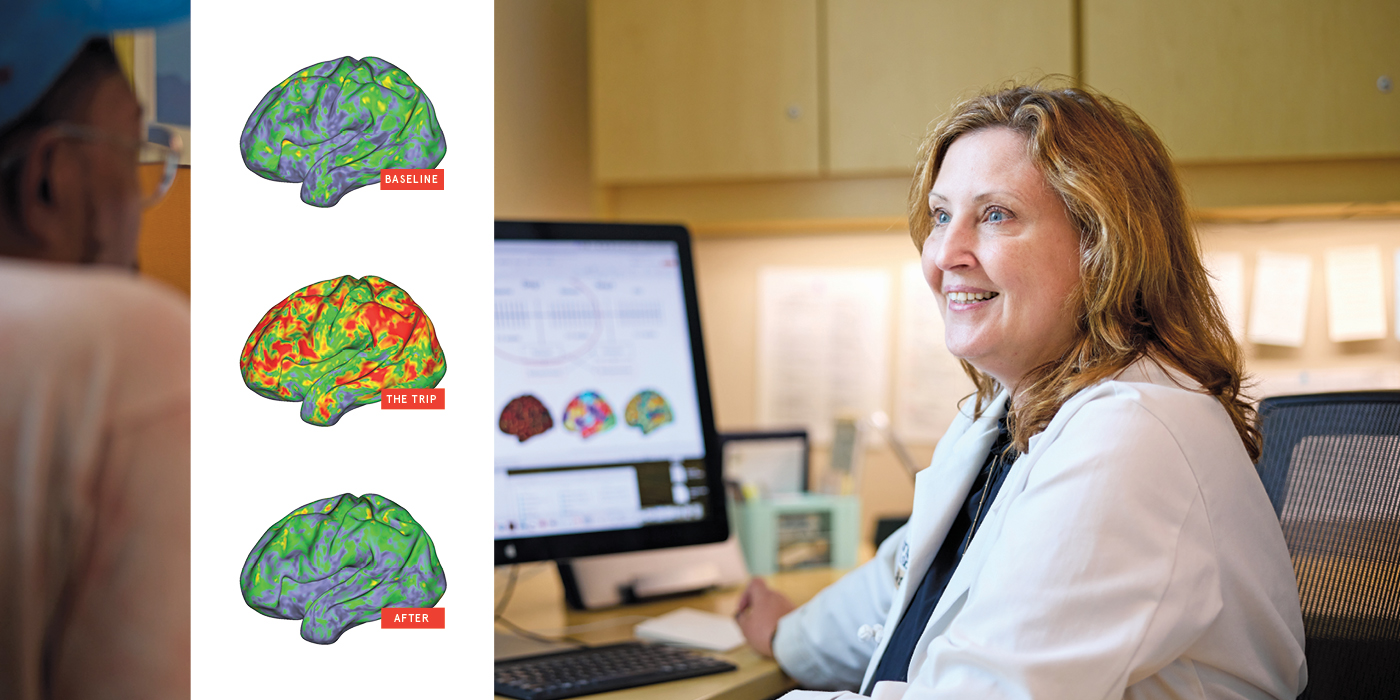

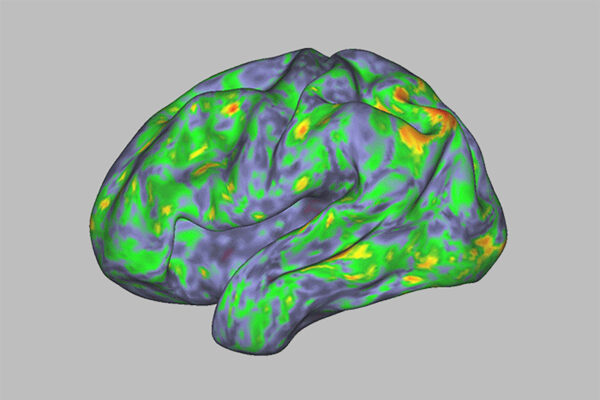

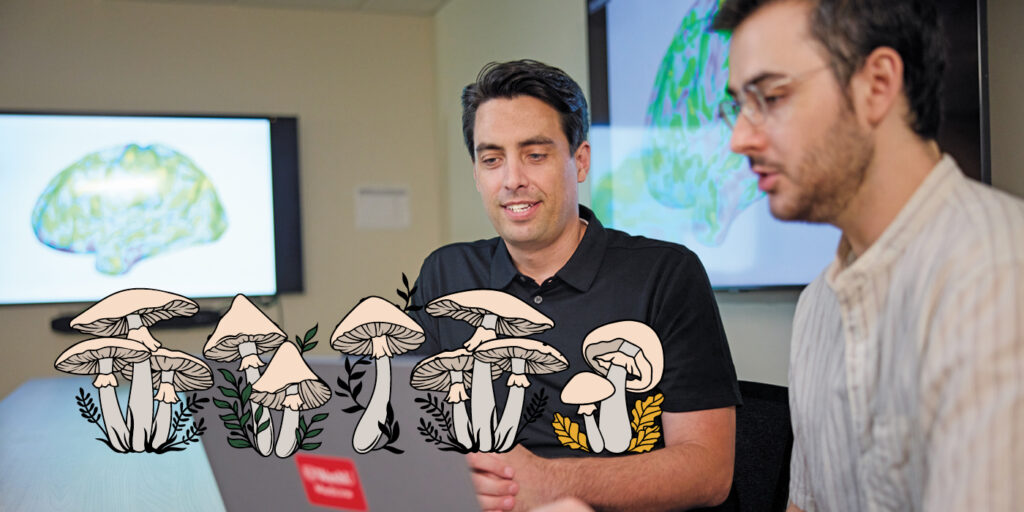

Over the summer, a study by Nicol and two other WashU Medicine neuroscientists went viral for its colorful depiction of the effects of a psychedelic drug on the brain. The New York Times ran a story on it with the headline “This Is Literally Your Brain on Drugs”; comedian Stephen Colbert cracked a joke about it on his TV show, The Late Show with Stephen Colbert. Published in Nature, the world’s leading scientific journal, and illustrated with brightly colored brain maps, the study showed that psilocybin disrupts typical patterns of brain activity, and that the degree of disruption correlates with the depth of the mystical experience felt by the participant. In short, it made psychedelic trips — famously difficult to put into words — visible to others through the magic of modern neuroimaging techniques.

The study could have been done only at WashU Medicine. It relied on a technique developed in 2017 by a group of WashU Medicine neuroscientists including Nico U. F. Dosenbach, MD ’08, PhD ’08, a professor of neurology and one of the co-senior authors on the 2024 study. Known as precision functional mapping, the technique uses data from hours of brain scans per person to construct personalized brain maps.

One way to think about the brain is as networks of areas that become active under the same conditions, such as while looking at an object or moving the body. One of the most important such networks is the default mode network, the set of areas made active when the brain is doing nothing in particular. The default mode network was discovered in 2001 by Marcus Raichle, MD, the Alan A. and Edith L. Wolff Distinguished Professor of Medicine at WashU Medicine and one of the world’s leading neuroimagers, when he noticed that a set of brain areas shut off in concert when a person began a task and then turned back on when the task was completed and the person’s mind was allowed to wander. Subsequent studies demonstrated the role of the default mode network in introspective thinking such as daydreaming and remembering. Using precision functional mapping, Dosenbach and colleagues showed that each person’s default mode network pattern is as unique and as stable as a fingerprint.

As part of the 2024 study, the researchers scanned the brains of seven healthy adults before, during and after taking high doses of psilocybin. They discovered that the drug temporarily obliterated the participants’ unique default mode network patterns.

“The brains of people on psilocybin look more similar to each other than to their ‘untripping’ selves,” Dosenbach says. “Their individuality is temporarily wiped out. This verifies, at a neuroscientific level, what people say about losing their sense of self during a trip.”

Dosenbach would know better than most what that means. Along with being one of the leaders of the study — with Nicol and Joshua Siegel, MD, PhD, then an instructor in psychiatry at WashU Medicine and now an assistant professor of psychiatry at New York University — Dosenbach was also a study participant. During his trip, he lost his sense of self, becoming by turns his son, his daughter, the universe and Raichle. “Some people take psilocybin and see God,” Dosenbach says. “I’m an atheist and a neuroimager, so I saw Marc Raichle.”

After falling out of sync, the network re-established itself when the acute effects of the drug wore off, but small differences from pre-psilocybin scans persisted for weeks. This observation jibes with other research studies showing that a single dose of psilocybin can have lasting effects.

During their trips, participants were asked to rate their feelings of transcendence, connectedness and awe using the validated Mystical Experience Questionnaire. The

30-item questionnaire provides a systematic way to assess the four core elements of a mystical experience — sacredness, positive mood, transcendence of time and space, and ineffability — and it is widely used in psychedelics research. The magnitude of the changes to the functional networks tracked with the intensity of each participant’s subjective experience.

For Dosenbach, the experience was at times electrifying, eye-opening and terrifying. And months later, he’s still not sure he’d ever do it again. He lost his ability to judge the passage of time or measure space, an unsurprising effect, he later said, of the disruptions to the parts of his brain involved in computing time and space.

For a few glorious moments, he even thought he had achieved every neuroscientist’s dearest dream: a deep and nuanced understanding of how the human brain works.

“Waves,” Dosenbach remembers telling Siegel, who was functioning as his guide during his psychedelic experience. “It’s all just waves.” Once the drug wore off, he recognized his earth-shattering insight as an illusion.

Nobody really knows how psychedelics ease suffering. A common hypothesis is that by disrupting established networks in the brain, the drugs create a window of opportunity to lay down new neural connections that translate into healthier ways of thinking and more appropriate neurological responses. Many researchers believe that successfully rewiring the brain requires the assistance of a trained therapist or facilitator.

“The psychotherapy component is indispensable,” says Leopoldo J. Cabassa, AB ’98, MSW ’01, PhD ’05, a professor of social work at the Brown School and co-director of the Center for Mental Health Services at Brown. “It’s about preparing someone for this experience, helping them through it, and then helping them integrate and learn from what has happened. These medicines create powerful experiences that can be frightening and confusing. Without proper support, these medicines can do additional harm to vulnerable people who are already suffering.”

“When people are suffering from potentially lethal psychiatric disorders, we don’t have that long to wait. Psychedelics work more rapidly than other available treatments.”

Ginger Nicol, MD

This unique combination of a psychoactive medicine and talk therapy is a new paradigm in mental health treatment. Its proponents hope that blending two modalities, each effective in its own way, will create treatments more powerful than either one alone.

“People say that psychedelics are useful because they change the brain, but all psychiatric treatments change the brain to some extent,” Nicol says. “Talk therapy changes the brain, too; it just does so very slowly. But when people are suffering from potentially lethal psychiatric disorders, we don’t have that long to wait. Psychedelics work more rapidly than other available treatments.”

Psychedelics are classified as Schedule 1 drugs, meaning they are officially considered to have no medical use and a high potential for abuse and, therefore, are tightly regulated. As WashU’s only faculty member authorized to work with Schedule 1 drugs, Nicol is the hub through which all psychedelic research at WashU must pass. (“I don’t want to be the rate-limiting factor, but I am,” she says.) To increase the institution’s capacity to provide regulatory support for other investigators to conduct research with psychedelics, earlier this year Nicol and Cabassa co-founded the Center for Holistic Interdisciplinary Research in Psychedelics (CHIRP). Supported by a grant from WashU’s Transcend Initiative that aims to promote universitywide, interdisciplinary collaborations, CHIRP includes faculty from WashU Medicine, the Brown School and Arts & Sciences. The center’s goal is to provide the infrastructure so WashU researchers in all fields can help build the body of knowledge needed to get these powerful therapies not only into the hands of doctors and therapists, but also into the lives of the people who need them.

Historically, researchers have developed treatments first and then started thinking about how they will be implemented, Cabassa says, and sometimes that means that a therapy that works great under controlled conditions turns out to be impractical.

“As we’re thinking about a psychedelic-assisted treatment, we’re also thinking about how we would get the treatment into practice in a way that is equitable, affordable and useful to the public.”

Leopoldo J. Cabassa, AB ’98, MSW ’01, PhD ’05

“Since the field of psychedelic-assisted therapy is so new, we have the opportunity to incorporate equity and implementation science components into all research from the beginning,” Cabassa says. “As we’re thinking about a psychedelic-assisted treatment, we’re also thinking about how we would get the treatment into practice in a way that is equitable, affordable and useful to the public.”

Nicol is also the WashU Medicine site leader for two clinical trials led by pharmaceutical companies to evaluate psilocybin-assisted therapies for depression. One of the goals of CHIRP, however, is to help WashU researchers design and lead their own studies of psychedelic-assisted therapies, taking full advantage of the university’s deep expertise in neuroscience, health equity and implementation science. Interest in doing such studies is high; CHIRP leadership is already considering proposed studies related to chronic pain, anxiety among people living with terminal diagnoses and burnout among health-care providers.

Earlier this year, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) accepted the first-ever new drug application for a psychedelic-assisted therapy when MDMA was submitted as a treatment for PTSD in conjunction with talk therapy. Evaluating the application created a unique challenge for the FDA, which regulates drugs but not psychotherapy. Arguing that it was neither equipped nor authorized to assess the psychotherapy element, the FDA focused on MDMA alone. In August, the agency rejected the application, saying that the sponsors had failed to prove MDMA safe and effective.

The failure hasn’t dampened public enthusiasm for the mind-bending drugs. Once a symbol of youth counterculture — and a traditional part of many Indigenous cultures for millennia before that — psychedelics have entered mainstream U.S. society in a big way. Celebrities such as Miley Cyrus, Elon Musk and Prince Harry have spoken publicly about their experiences with microdosing — taking tiny doses too low to trigger a psychedelic trip — and the benefits they see in terms of improving mood, enhancing creativity and promoting empathy. Oregon became the first state to decriminalize psychedelics in 2020. As of 2023, Oregon residents can visit regulated clinics to obtain psychedelic-assisted therapy, no doctor’s note required. Missouri lawmakers submitted bills in the state House of Representatives to legalize psilocybin therapy for veterans in 2023 and 2024, though neither bill was enacted into law.

The pace of scientific research doesn’t look likely to slow down. In January, the Veteran’s Administration announced that it would start supporting psychedelic studies for depression and PTSD. In April, the Department of Health and Human Services announced a $22 million funding opportunity for research on psychedelic-assisted therapy for chronic pain in older adults.

“This is a new treatment paradigm, and it’s going to take some time for us to learn how best to use it,” Nicol says. “But it’s a new paradigm with ancient roots.

Indigenous people have been using these medicines for thousands of years. There’s a lot of wisdom and experience already out there. We’re trying to do good science, in partnership with our community, so that the questions that get asked are the right ones and we learn how to use these drugs as safely, effectively and equitably as we possibly can.”