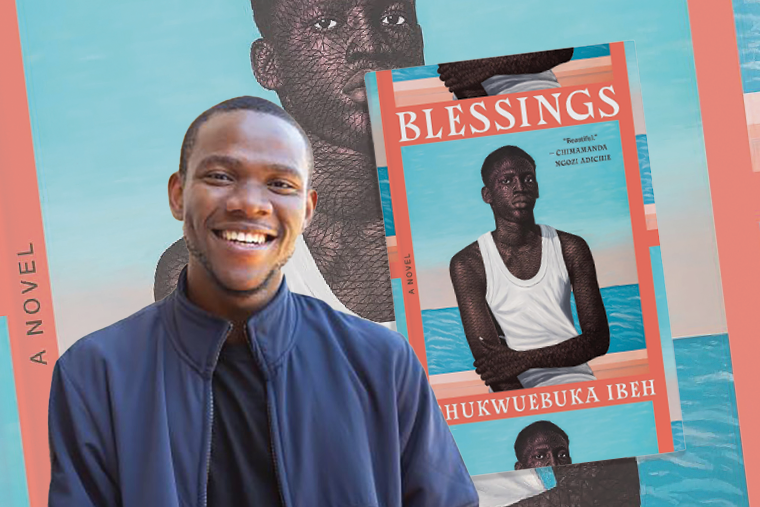

Chukwuebuka Ibeh, MFA ’24, grew up in Port Harcourt, Nigeria, in what he calls “a family of storytellers.” First enthralled by his grandmother’s tales, he later took over her role with stories of his own.

But after reading Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie’s Purple Hibiscus, a coming-of-age novel set in Nigeria, Ibeh realized two things: First, there was a path for a young person from his home country to become a writer; second, talent alone wasn’t enough. He knew he needed more training beyond his bachelor’s degree in history and international studies from Nigeria’s Federal University and began researching MFA programs worldwide. “WashU’s MFA program kept coming up again and again, so I applied with no hope or expectation of getting in,” he says. But he did. “The best day of my life,” he says.

So Ibeh, who had never traveled out of Nigeria, arrived in St. Louis in 2022 with a few published short stories and a first draft of a novel. And it was on the Danforth Campus — beginning in the class of Kathryn Davis, the Hurst Writer in Residence in Arts & Sciences — where he began workshopping Blessings, published by Doubleday in June. It’s a story of a young man in Nigeria coming to grips with his homosexuality at a time when such tendencies were not only marginalized but also ostracized and, eventually, criminalized.

Blessings’ protagonist, Obiefuna, is a teenager when the story begins in 2006 and an adult when it culminates with Nigeria’s Same Sex Marriage (Prohibition) Act of 2013. Along the way, he deals with a disapproving father who sends him to boarding school after witnessing him and another boy in a chaste, intimate encounter; an understanding mother who is battling breast cancer; and a series of relationships that open up Obiefuna’s world, offering at times hope and love, pain and devastation.

It’s a coming-of-age story about being queer in a country where no one wants to acknowledge queerness, and it’s also about family, lost and found. Obiefuna is a layered, textured character who has the reader rooting deeply for him yet frustrated over some of his choices.

“I didn’t want to make Obiefuna one-dimensional,” Ibeh says. “As much as I wanted to portray him as a victim of circumstances, I wanted to show that victims can also be bullies. I wanted to show that somebody could be both good and evil.”

The novel is particularly compelling in the aftermath of the Nigerian law that criminalized same-sex marriage as a response to gay rights being broadened in the U.S. and around the world. Ibeh is able to capture how it feels to live in a country where basic human rights — in this case whom and how to love — are taken away.

“It wasn’t just criminalizing gay marriage,” Ibeh says. “It criminalized pretty much any form of LGBTQ+ rights advocacy.”

That was 11 years ago. Since then, the law has been challenged in Nigerian courts, and Ibeh says his home country is making small steps toward progress. Yet he admits to having been nervous about the book’s publication and how it would be received in Nigeria. But the reception has been positive there as well as in the U.S., where it was included on USA Today’s “Best Books by Black Authors to Read in 2024” list.

Ibeh was most gratified by the reaction of his fellow Nigerians. “When people come up to me and say, ‘Obiefuna is me’ or ‘I would never have the courage to write this but I’m glad it exists,’ that makes me happy,” says Ibeh, who remains at WashU on a teaching fellowship. “I did what I set out do.”