The typical WashU Danforth Campus tour tells upbeat stories about student life and academics while taking you from the east end of campus to the South 40. You learn about WILD in the Quad, the fun of painting the underpass and the strange reason we don’t have sorority houses.

But there’s another story hidden in the names and history of WashU’s campus. And there’s another tour that tells you about the university’s darker history, one connected to slavery and racial injustice.

This self-guided tour starts at the George Washington statue that stands in front of Olin Library and reminds you that Washington University is named after someone who held 317 people in slavery at the time of his death. At Crow Hall, you learn that Wayman Crow, one of the university’s founders and former trustees, was an enslaver. Walking along Ellenwood Avenue, you learn about the history of slavery in the area, and that the Danforth Campus and South 40 occupy land where people were enslaved by the Forsyth and Skinker families.

The “Enslavement and Its Wake” tour is part of the WashU & Slavery Project, an initiative started in spring 2021 to advance scholarship around WashU’s history with slavery. But the project is also reshaping public history in the St. Louis region by striving to add or improve information around slavery and racial discrimination at area historical sites, including the General Daniel Bissell House and the Missouri Botanical Garden.

The WashU & Slavery Project is part of Universities Studying Slavery, a consortium of more than 100 universities across North America, Colombia and the U.K. that are uncovering how their institutions were involved in human bondage and legacies of racism.

Geoff Ward, professor of African and African American studies in Arts & Sciences and director of the WashU & Slavery Project, advocated for WashU to join the consortium in 2020 when Chancellor Andrew Martin asked senior faculty for ideas on how the university might further commit to dismantling structural racism.

“It is important for our university to acknowledge any entanglements with slavery. It is taking a step toward truth-telling and reconciliation.”

Beverly Wendland

Ward suggested the university join for three reasons: (1) Research in this area shows that it is important to address these legacies; (2) it would allow WashU to better prepare our students to understand and address structural racism as it relates to the history and legacy of slavery; and (3) it would offer WashU the opportunity to be a more meaningful, valuable partner in the local, regional and international efforts to grapple with these issues.

University leadership agreed. “It is important for our university to acknowledge any entanglements with slavery,” says Beverly Wendland, provost and executive vice chancellor for academic affairs. “It is taking a step toward truth-telling and reconciliation. It helps to uncover and acknowledge past injustices, which is essential for healing and moving forward.”

The University of Virginia (UVA) started the consortium in 2016. UVA used enslaved labor to build its campus and, like other schools in the con-sortium, is dealing with these direct ties to slavery.

Washington University’s relationship to slavery is different. According to Ward, no evidence has been found that enslaved people built the university or labored on campus (the first buildings on the current Danforth and Medical campuses were built in the early 1900s, years after the Emancipation Proclamation). Yet the story of William Greenleaf Eliot, who was a founder of the university in the mid-1800s and long touted as an abolitionist, needed updating.

A team of student researchers contributing to the WashU & Slavery Project discovered that Eliot wasn’t as staunch an abolitionist as previously thought. Students in “Rethinking WashU’s Relation to Enslavement: Past, Present and Future” — a course taught by Iver Bernstein, professor of history, African and African American studies, and American culture studies, all in Arts & Sciences, and Carl Craver, professor of philosophy and philosophy-neuroscience-psychology in Arts & Sciences — showed that Eliot actually owned enslaved people. He bought them for the purpose of freeing them, but he required the enslaved to work for a while to recoup his expenses. He also only supported conditional and gradual emancipation of Blacks and wanted Blacks sent to Liberia once they were freed.

Students combed through Eliot’s papers at Olin Library and found, among other evidence, that in 1853 — the year Washington University was founded — Eliot wrote a letter to the editor of The Christian Messenger saying he “would not advise the present emancipation of those in bondage.” The students published their findings in Student Life in 2021, and the article was picked up by local media.

The students do acknowledge that Eliot made many positive contributions to St. Louis, such as founding the Western Sanitary Commission (WSC) during the Civil War. A precursor to the Freedman’s Bureau, the WSC provided field hospitals, housing and other support to Civil War refugees — white and Black, soldiers and civilians — up and down the Mississippi River Valley. Eliot also rescued and befriended Archer Alexander, an enslaved man who told Union troops about a Confederate plan to destroy a bridge. (Washington Magazine published a feature story on their relationship, “Of friendship and freedom,” in spring 2016.)

“Much of what we’re learning is through the research of our students,” Ward says, and this research showed that the university’s relation to slavery was “profoundly nuanced.”

Pushing back on whitewashing

Ward credits collaboration among faculty, staff, students and community partners with guiding the early development of the project. Key here is Kelly Schmidt, who joined the project as a postdoctoral researcher and is now a reparative public historian in WashU Libraries, a lecturer in the Department of African and African American Studies and associate director of the project. Schmidt teaches courses such as “Catholicism and Slavery,” “St. Louis Black History, Culture, and Civic Engagement” and “Slavery and Public History.” And the last two dovetail with the WashU & Slavery Project.

Instead, the course teaches “students how to apply history in public settings for people who aren’t academics and to work with communities in telling the stories of slavery in St. Louis so that the stories are not forgotten.”

Kelly Schmidt

“The ‘Slavery and Public History’ course is meant to move beyond teaching the history of slavery as you would in a traditional history class,” says Schmidt, who previously worked with Saint Louis University on the U.S. Jesuits’ “Slavery, History, Memory, and Reconciliation” project. Instead, the course teaches “students how to apply history in public settings for people who aren’t academics and to work with communities in telling the stories of slavery in St. Louis so that the stories are not forgotten.”

The course is interactive. Schmidt takes students on a campus tour. (She is the one who designed the WashU & Slavery Project’s “Enslavement and Its Wake” tour.) They visit different sites around the St. Louis area, including White Haven, a home Ulysses S. Grant shared with his wife, Julia Dent, who held people in slavery. Plus, students have been able to meet virtually with representatives from the Highland’s Council of Descendant Advisors, a group made up of the descendants of enslaved people from President James Monroe’s Highland estate, in Charlottesville, Virginia.

When they visit historical sites, students use best practices they’ve learned in class to evaluate how the sites are dealing with their legacy of slavery. In addition to analyzing the tour and exhibits, students also assess if appropriate media are being used to tell the story, how text is integrated into the tour’s interpretive frame and if the scholarship is current.

Students work with some sites to improve their historical offerings. For example, Arielle Hatton, Arts & Sciences Class of ’26, and Sandra Meszaros, AB ’23, revised and designed, respectively, interpretive panels about enslavement at the General Daniel Bissell House in north St. Louis. Hatton and fellow students Cameron Chambers, AB ’24; Daniel Radke, Engineering Class of ’27; and Allen Willis, Arts & Sciences Class of ’27, helped nominate the Bissell House as a site for the National Park Service’s Underground Railroad Network to Freedom — as a site people escaped from, not to. And their interpretive panels will go up this year.

And Bissell House wasn’t the only site the WashU & Slavery Project helped nominate to the National Park Service’s Underground Railroad Network to Freedom.

Keona Dordor, AB ’24, who while a student was a Civic Scholar with the Gephardt Institute for Civic and Community Engagement, researched people interred at Greenwood Cemetery, in the St. Louis suburb of Hillsdale, who used or aided the local Underground Railroad. Greenwood was the first commercial and nonsectarian cemetery for Blacks in St. Louis, and Dordor’s work led to the cemetery becoming part of the park service’s Network to Freedom.

“Getting younger people involved in preservation work is imperative,” says Dordor, who majored in urban studies. “Last summer, most of the people I interacted with in preservation fieldwork were older. Being the only young person in these spaces made me nervous about what the future would look like for preservation projects.

“I would argue it is one of the most urgent things that young people can get involved in, mainly because correct and accurate history is under attack,” Dordor says.

A database makes the enslaved visible

In December 2018, Carl Craver was on a biking trip in Natchez, Mississippi, with a friend, and it was not going great.

“During the day, we would visit these mansions, and I kept getting more and more irritated about the whitewashing of this history,” Craver remembers. So he suggested they go to Forks of the Road — “the second- largest domestic slave market in the Deep South,” according to the National Park Service, which maintains the site.

“I expected to find a national park with an office,” Craver says. “Instead, we got there and saw this little patch of land where they had poured some cement in the ground and threw some shackles in it. There was a sign that was a barely functioning historical marker.”

Craver became despondent. And he remembers expressing as such to his friend, stating, “This place is sick. These people are sick. And they’re not going to get well until they know of every person who passed through this place.”

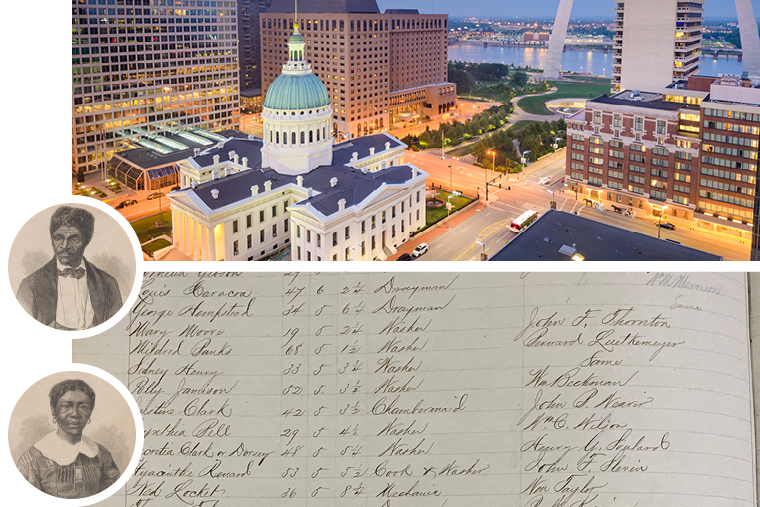

After returning home, Craver realized he didn’t know much about the history of St. Louis. So he started looking into slavery here, and he discovered, among other shocking facts, that the east steps of the Old Courthouse were a regular site for slave auctions.

“The centerpiece of our skyline is a slave market,” Craver says, still surprised. Many iconic images of St. Louis feature the Gateway Arch perfectly framing the Old Courthouse. “And I thought again, ‘This place is sick. We are sick.’”

But “what’s valuable in those sources in particular, is you get names of people enslaved and sometimes family relationships. They’re the beginnings of a narrative, the beginnings of a life story.”

Carl Craver

Only this time, Craver thought that perhaps as a professor of philosophy at WashU he was in a position to learn some history and, in the process, contribute to the effort to remember people enslaved in St. Louis. He wanted to begin, in bits and pieces, to assemble what we could of their names and stories. After all, he had access to extremely talented students who wanted to learn by doing. All he had to do was focus their energies and talents on this project.

“Historians at Gateway Arch National Park had collected documents about court-ordered slave sales,” Craver says. Yet the records were all categorized by enslaver.

But “what’s valuable in those sources in particular,” Craver says, “is you get names of people enslaved and sometimes family relationships. They’re the beginnings of a narrative, the beginnings of a life story.”

Craver wanted to reorganize the information into a database focusing on the biographical information of those enslaved, not on the enslavers. The St. Louis Integrated Database of Enslavement, aka SLIDE, was born. Craver then partnered with undergraduate and graduate students (now numbering more than 20, and counting), the Humanities Digital Workshop and the WashU & Slavery Project to build the database, record by record, name by name.

This isn’t the first time Washington University has digitized enslavement records. In 2013, the university concluded the St. Louis Freedom Suits Legal Encoding Project, an initiative of the Digital Library Services unit of Washington University Libraries. It digitized some of the 300 St. Louis Circuit Court cases where enslaved people sued for freedom, most famous among them Dred and Harriet Scott.

Schmidt oversees the day-to-day work on the SLIDE database, which has gone through several iterations as the team figures out how best to organize the information. But Craver’s students still contribute as part of their coursework and in independent studies.

Francisco Perez, Arts & Sciences Class of ’27, is taking Craver and Bernstein’s course “Rethinking WashU’s Relation to Enslavement,” and as part of the course, he and the other students input data about freedom bonds records (licenses and sponsorships required of all free Black people in St. Louis starting in 1935) into SLIDE.

“Across our nation, Black history is being erased,” Perez says. “And it is projects like these, repositories like these, that will ensure our history doesn’t get erased — that will ensure this information is not ‘gate-kept,’ but instead is accessible and transparent for the public to see.”

Students use multiple sources — freedom bonds, runaway slave ads, census data, court-ordered slave sales and more — to create entries for each enslaved person and enslaver in the hopes that descendants will be able to find their ancestors.

In one instance, Perez discovered a freedom bond for Joseph W. Postlewaite. Sometimes a person’s occupation, age and height will appear on a freedom bond, but that wasn’t the case for Postlewaite. So Perez did additional research and found Postlewaite had been a famous composer in the mid- to late 1800s.

“It just shows that bonds can lead to treasures of information,” Perez says.

Henry Shaw and WashU’s contested past

Sylvia Sukop is a student in the track for international writers in the Germanic languages and literatures doctoral program, and her research is focused on the commemoration of difficult histories, for example, slavery in the U.S. and the Nazi Holocaust in Europe. She jumped at the chance to participate in “Memory for the Future: A Public Humanities Lab,” which dealt with difficult histories including slavery, racial violence, the Holocaust and more.

Ward and historian Anika Walke, the Georgie W. Lewis Career Development Professor in Arts & Sciences, taught the course — a one-year studiolab offered through the Center for the Humanities that combines the formats of the classroom and the lab.

“Their course was fantastic,” says Sukop, a Spencer T. and Ann W. Olin Fellow. “By having us complete a public-facing project, it provided me with a foundation to think about my upcoming dissertation in light of my own public humanities practice.”

For her community project, Sukop formed two key partnerships. First, she collaborated with cultural preservationist Angela da Silva, a public historian who researches and performs stories of the lives of 19th-century enslaved people in Missouri.

One significant story da Silva shares is that of Mary Meachum, the widow of the abolitionist preacher John Berry Meachum, who assisted enslaved people fleeing to the free state of Illinois. Once in 1855, for example, nine enslaved people, including four owned by Missouri Botanical Garden founder Henry Shaw, crossed the river with Mary Meachum’s help. Four escaped, but armed bounty hunters recaptured five, including a woman named Esther and her two children. As punishment, Shaw separated Esther from her children and sold her down-river in Mississippi. Meachum was immediately arrested.

Since 2002, the Mary Meachum Freedom Crossing Celebration, co-founded by da Silva, reminds St. Louis of this history. The event is held at the Mary Meachum Freedom Crossing, a federally recognized Underground Railroad Network to Freedom site on the west bank of the Mississippi River. Located on what da Silva calls “holy ground,” near where freedom seekers tried to cross to Illinois, the site today is part of the Great Rivers Greenway system.

With Ward’s support, Sukop initiated a Mentored Professional Experience (MPE) with her second community partner, the Missouri Botanical Garden (MBG). Beginning in spring 2023, Sukop worked for three semesters with Sean Doherty, MBG’s vice president of education, to develop narratives and public programming addressing Shaw’s slave-owning past.

Henry Shaw came to the United States in 1819 from Sheffield, England, settling in St. Louis where he opened a prosperous general store. Sukop says when he first came to St. Louis as a young man, Shaw expressed anti-slavery views. But beginning at age 28 and persisting for more than three decades, he enslaved both adults and children, even hiring some of them out for their labor and taking their wages.

“As I learned more about this history,” Sukop says, “I was shocked by the level of exploitation and dehumanization that went on.”

While Shaw’s business records document his ownership of enslaved people and are publicly accessible on the MBG website, the archive provides little information about the enslaved themselves. Sukop has been combing through the archive, including personal letters and journals, in search of any mentions of enslaved individuals that might provide some sense of their humanity.

“We’re hoping to develop narratives and modes of telling a fuller story,” she says. “During my MPE, I researched innovative models at other institutions around the country — for example, the Rooted Wisdom initiative at the Adkins Arboretum in Maryland — and introduced some of those ideas to the garden and arranged Zoom meetings for our staff to talk to theirs.”

“A lot of people think, ‘Oh, that means Henry Shaw’s Tower Grove House was a safe house on the Underground Railroad.’ And it’s the opposite. The reason it was awarded the designation is Shaw’s enslaved fled from there to seek their freedom.”

Sylvia Sukop

Some of Sukop’s work was folded into MBG’s application to the National Park Service to have Tower Grove House added to the Underground Railroad Network to Freedom.

“I find there’s public confusion about what that means,” Sukop says. “A lot of people think, ‘Oh, that means Henry Shaw’s Tower Grove House was a safe house on the Underground Railroad.’ And it’s the opposite. The reason it was awarded the designation is Shaw’s enslaved fled from there to seek their freedom. Shaw did not have sympathies with abolition, and he owned people up to and including (what was known then as) Shaw’s Garden’s grand opening in 1859.”

Shaw’s story is entwined with WashU’s, too. In 1885, Shaw endowed the Henry Shaw School of Botany at the university,

“I think what Geoff (Ward) and Kelly (Schmidt) have done — so powerfully, so eloquently, so deeply — is they have helped us surface these kinds of connections among elite St. Louis individuals and institutions of the 19th century and shown that these were not separate stories,” Sukop says. “They’re all entwined.”

Today, MBG and WashU are once again partnering on scientific research and education projects around plant conservation — and now around the study and interpretation of slavery and freedom in St. Louis.

WashU & Slavery Project keeps expanding

The early history of WashU is filled with enslavers like Henry Shaw. According to Ward’s 2023 Martin Luther King Jr. Day Commemoration keynote — “Can St. Louis Become the Beloved Heart of America?” — several of our early founders and trustees were enslavers.

Capt. John O’Fallon was one of the largest slaveholders in the state and led its anti-abolitionist movement. He was also one of the university’s early benefactors and founders of the School of Medicine.

O’Fallon reportedly led the grand jury that declined to indict anyone for the lynching of Francis McIntosh, a Black man who stood accused of stabbing two policemen. When a white mob broke him out of jail and began burning him alive, McIntosh was in such pain he begged someone to shoot him.

Later, one of Washington University’s first buildings, the O’Fallon Polytechnic Institute, was built near the intersection where McIntosh was murdered, and WashU Law School later started there.

Washington University also did not stand at the forefront of desegregation. While the Law School in 1889 had its first Black graduate, Walter Moran Farmer, his classmates refused to walk with him during graduation according to a Missouri Courts article. Atiya Chiphe, Arts & Sciences Class of ’26, says she found it while conducting research on Black graduates as a WashU & Slavery Project Scholar. The scholars program was created to increase student participation and contributions in project priority areas.

After Farmer, WashU didn’t admit Blacks until the School of Medicine unintentionally admitted a Black student in 1947. Even though President Harry S. Truman’s Commission on Higher Education asked states that same year to repeal segregation in higher education laws, undergraduate programs at WashU weren’t open to Black applicants until 1952.

The WashU & Slavery Project is learning how histories and legacies of slavery and colonialism touch not only the medical school but every school within the university. A project steering committee was recently created to bring faculty and staff from the School of Medicine, School of Law, Sam Fox School, and the Center for the Study of Race, Ethnicity & Equity into more direct advisory roles, helping guide project planning and integration throughout the institution.

Many questions remain. The project continues to revisit the Lucas Place neighborhood where the school’s early downtown campus was located, for example, and research is ongoing regarding all the enslavers who have had ties to WashU.

“We need to find ways to bring more of our community into a recognition of this problem. The ‘yoke of history’ guides our behaviors and institutions down particular paths, and we need to be intentional about changing course.”

Geoff Ward

Much is left to be done, but for Ward, an overarching question looms: “How should WashU acknowledge this past, and how should we address its legacies in our campus and community?”

Ward points out that the project can inform answers to this question, but answers will have to come from university leaders, and ultimately the entire WashU community.

One result to date: Washington University has established a framework to examine issues of naming or renaming buildings and other spaces, professorships and scholarships. And the university has appointed a Naming Review Board to which members of the community can submit requests for named features to be reviewed. The framework and process was approved by the Board of Trustees Dec. 1, 2023.

The past will not remain buried; in fact, it never really was, Ward says. “The past maintains a presence,” he says. “We know from a vast body of social science and humanities research that histories of slavery continue to help explain contemporary patterns of conflict, violence and inequality.

“We need to find ways to bring more of our community into a recognition of this problem,” Ward continues. “The ‘yoke of history’ guides our behaviors and institutions down particular paths, and we need to be intentional about changing course.”

Through reconciling with our pasts, we open up our futures.