How and when did the solar system and planets form? Is there other life out there? Many have pondered these questions, and planetary scientists like Meenakshi Wadhwa, PhD ’94, are getting closer to answering them and many more.

For Wadhwa, it all started where she grew up, in India, in the foothills of the Himalayas. She spent much of her time as a kid outdoors collecting rocks and wondering how mountains were formed. This interest inspired her to study geology at Panjab University in Chandigarh, India, where she became interested in the geology of other planets. After graduating, Wadhwa began researching doctoral programs and decided to move to the U.S. to attend Washington University because of its strong earth and planetary sciences program. When her PhD adviser, Ghislaine Crozaz, introduced her to Martian meteorites, Wadhwa was hooked.

“She and her late husband, Robert Walker [founding director of the McDonnell Center for the Space Sciences], were both hugely influential on my development as a scientist and on my career path,” Wadhwa says. “Not only did they provide me with professional mentorship, but they also treated me like family, which was so important to me as an international student whose family and friends lived half a world away.

“Even after I graduated, they were my sounding board before I made any significant decisions, and I will always be grateful for their mentorship and support that put me on the path to where I am today.”

At WashU, Wadhwa studied Martian meteorites to learn about the planet’s evolution and had the opportunity to travel to Antarctica as part of the U.S. Antarctic Search for Meteorites (ANSMET) program. “Both Ghislaine and Bob had previously gone to Antarctica as part of the ANSMET program, and hearing about their fantastic experiences there inspired and motivated me,” Wadhwa says. “It was a life-changing experience.”

After graduation, she headed to the University of California San Diego as a postdoctoral researcher and studied planetary materials to better understand the time scales of events occurring in the earliest history of the solar system. Six months later, Wadhwa was offered the position of curator of meteorites at the Field Museum in Chicago, which houses one of the world’s best collections of meteorites.

Yet she was hesitant about accepting the position. “The museum had few analytical facilities, and, as a geochemist, I needed analytical tools for my research,” Wadhwa says. She turned to her lifelong mentors for advice. “Bob said, ‘Treat this opportunity as your blank canvas and paint your own picture!’ They both encouraged me to consider this an opportunity to create something from the ground up.”

“The [Mars Sample Return] program gives us an opportunity to answer that fundamental question we have as humans — ‘Are we alone in the universe?’ — and will pave the way for astronauts to explore Mars someday.”

Meenakshi Wadhwa

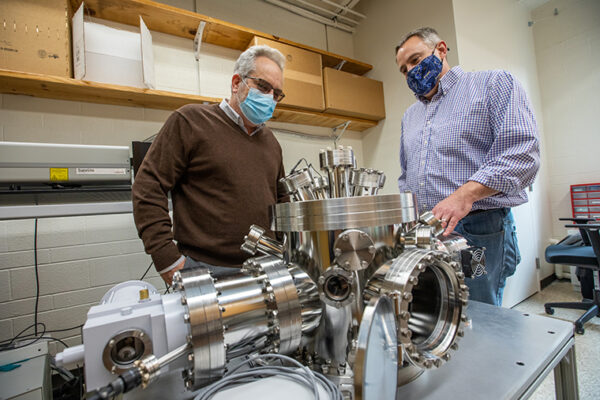

During her time at the Field Museum, Wadhwa built a state-of-the-art geochemical laboratory, where she could conduct research to understand the processes and time scales of events in the early solar system and on planetary bodies.

Eleven years later, in 2006, Wadhwa headed to Arizona State University (ASU) to serve as director of the Center for Meteorite Studies. Today, she is director of the School of Earth and Space Exploration. Her main goal? “I want to propel ASU to be among the leading institutions in the world for exploring the Earth and space,” she says.

While on sabbatical in 2012, Wadhwa returned to Antarctica with the ANSMET program. “It was just as amazing as I remembered,” she says. “Antarctica is one of the most breathtakingly beautiful and wondrous places on our planet.”

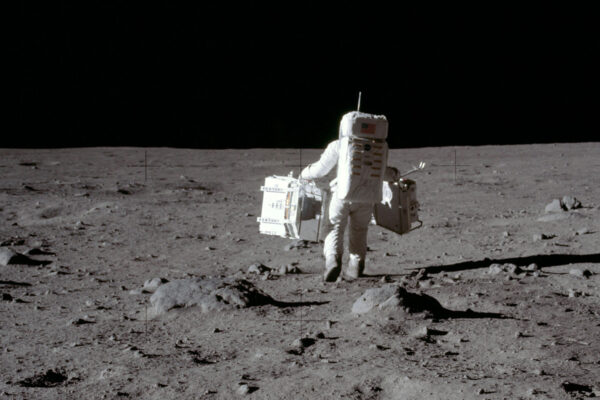

Having first studied Martian meteorites in graduate school, Wadhwa has long dreamed of studying actual Martian rocks returned by a spacecraft mission. An out-of-this-world opportunity emerged in 2021 when she was offered the position of principal scientist for the Mars Sample Return (MSR) program, a collaboration between NASA and the European Space Agency to return Mars samples currently being collected by the Perseverance rover to Earth.

“By bringing back these samples and studying them in detail in laboratories here on Earth, we can try to understand the formation history of Mars and the geologic context of where, when and how life might have originated there,” Wadhwa says. “This could give us insights into how life might have originated on Earth.

“The MSR program gives us an opportunity to answer that fundamental question we have as humans — ‘Are we alone in the universe?’ — and will pave the way for astronauts to explore Mars someday.”