Colors float on a gentle breeze. Fabric sheets tower like canyon walls. Plumes of red and gold erupt with almost geological force.

Over the last three decades, Katharina Grosse has emerged as one of Germany’s most prominent contemporary artists, known for sprawling murals, installations and other in situ works that investigate the nature of color and its capacity to destabilize visual hierarchies. “Color can appear anywhere,” Grosse explains. “It is independent from any location. … Color gets to you like noise, a scent or a taste.”

In 2016, the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum at Washington University commissioned Grosse to create a vast, two-story abstract mural for the Gary M. Sumers Recreation Center as part of the museum’s Art on Campus program. Last fall, the Kemper Art Museum presented “Katharina Grosse Studio Paintings, 1988-2022: Returns, Revisions, Inventions.” The first survey to highlight the artist’s work on canvas, the exhibition was both a yearslong curatorial effort and a demonstration of the museum’s commitment to work by contemporary and international artists.

“Katharina Grosse is one of the most stimulating, creative and thoughtful painters working today,” says Sabine Eckmann, the William T. Kemper Director and Chief Curator at the Kemper Art Museum, who organized the exhibition in collaboration with the artist. “Her practice stretches the boundaries of painting in all directions.”

Currently on view at the Kunstmuseum Bern in Switzerland, “Katharina Grosse Studio Paintings” featured 37 large-scale canvases as well as an interactive installation commissioned for the exhibition (see previous spread). A bilingual scholarly catalog, co-published by the Kemper Art Museum and Hatje Cantz, includes more than 100 additional images and serves as the first in-depth reference on Grosse’s studio painting.

The exhibition was organized into two thematic sections. “Returns, Revisions, Inventions” (from which the overall exhibition takes its title) highlights Grosse’s intuitive process and the ways shape, color and texture can echo across multiple canvases.

This section also featured some of Grosse’s earliest use, in the late 1990s, of commercial paint sprayers. At a time when international gestural painting was largely dominated by male painters, Eckmann notes, these works contested the importance of direct connection to the artist’s hand, and thus the supposed link between painting and artistic subjectivity.

The second section, “Fissures and Ruptures,” emphasized the ways Grosse challenges the alleged autonomy of painting, stretching its boundaries and physical properties.

For example, since the early 2010s, the artist has combined her use of sprayers with stencils to produce spatial voids that paradoxically become active players on the visual field. Compressed, fractured and destabilized, these paintings-within-paintings defy all sense of chronological order.

More recently, Grosse has upended analogies between art and nature by adhering tree branches to the canvas and spray-painting over them. In other works, she has experimented with slashed canvases that both reveal and incorporate the white museum walls. “Colors are relational elements,” Grosse observes. “They look a certain way only in relation to something else. But there’s no hierarchy. Color can turn any direction at any moment.”

African Modernism in America

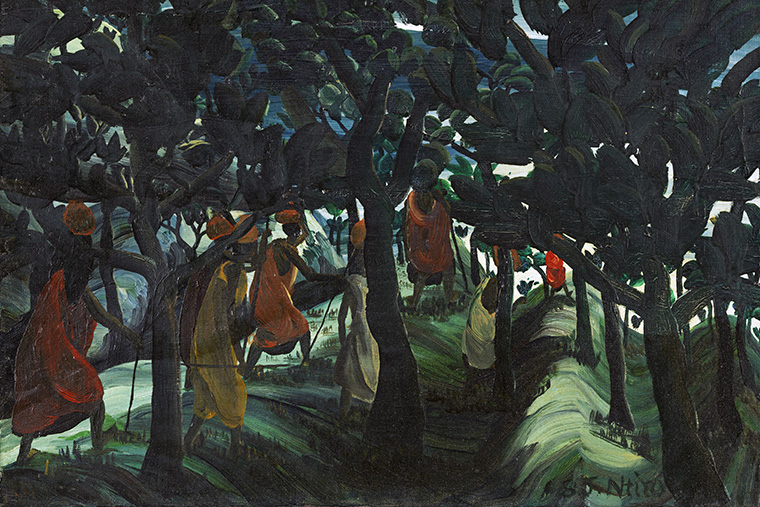

Seven figures glide through a rolling evening forest. Each bears a wedding offering of mbege, a beer made from fermented bananas, carried in gourds atop their heads.

In “Men Taking Banana Beer to Bride by Night” (1956), Tanzanian-born painter Sam Joseph Ntiro deploys a muted palette and swirling, almost-abstract brushstrokes to present a traditional scene of the Chagga people. The effect is pastoral and radical — a hopeful premonition for Tanzania’s coming independence.

Now on view at the Kemper Art Museum, through Aug. 26, the painting is among the many highlights of “African Modernism in America.” The exhibition, organized by the American Federation of Arts and Fisk University Galleries in Nashville, is the first traveling survey to explore the complex relationships between African and African American artists, patrons and cultural organizations during the 1950s and 1960s, amidst Africa’s tumultuous independence period.

“Modernism, at its core, is an aesthetic response to the conditions of modernity,” says Perrin M. Lathrop, assistant curator of African art at the Princeton University Art Museum, who co-curated the exhibition, with Nikoo Paydar and Jamaal Sheats, while at Fisk. “That response takes many forms. It can emerge from exposure to different cultures or different visual media, but it also arises from traditional cultural practices that, with ingenuity and creativity, incorporate a sense of contemporaneity.”

Encompassing more than 70 artworks by nearly 50 artists, “African Modernism in America” opens with an exploration of the Harmon Foundation, which in the mid-20th century was a leading U.S. promoter of African diaspora art. For example, in 1960, the foundation helped arrange for the Museum of Modern Art in New York to acquire Ntiro’s “Men Taking Banana Beer to Bride by Night” — the first work by an African artist to enter MoMA’s permanent collection.

The exhibition also explores the continent-wide networks of artists, galleries, journals and education programs that supported postcolonial African artists. For example, Demas Nwoko and Uche Okeke both studied at the Nigerian College of Arts, Science and Technology in Zaria, where faculty included Etso Clara Ugbodaga-Ngu. Nwoko and Okeke also exhibited together at the Mbari Artists and Writers Club in Ibadan, which later hosted an exhibition by the American artist Jacob Lawrence, during the latter’s first visit to Nigeria.

Other sections explore how African and African American artists navigated Cold War politics, decolonialization and the U.S. civil rights movement. For example, John Biggers’ “Kumasi Market” (1962) — a painting once owned by Maya Angelou — reflects the American artist’s travel through Ghana in 1957, the same year that nation gained independence from Great Britain. “Yoruba Forms #5” (1969) by David Driskell, longtime head of Fisk’s art department, is informed by the artist’s reverence for traditional African sculpture and deep knowledge of global aesthetic philosophies.

New acquisition highlights

In August 2009, artist and activist Ai Weiwei was arrested in Chengdu, China. As police escorted him into a hotel elevator, Ai snapped a selfie. The image, later shared on social media, quickly became one of the best-known examples of political resistance in 21st-century art.

As part of its commitment to collecting work by contemporary artists, the Kemper Art Museum recently acquired a monumental version of this now-iconic work. Measuring more than 12 feet wide by 10 feet tall, “Illumination” (2019) reproduces Ai’s selfie in colorful Lego bricks. “Legos are a playful and broadly accessible commercial medium,” Eckmann says, “and thus an effective tool for spotlighting political injustices.”

Viewed from a distance, or in reproduction, “Illumination” can be difficult to distinguish from its source. Both depict the artist and a friend, musician Zuoxiao Zuzhou, flanked by officers in a hotel elevator, camera flashing like a halo overhead. But as the viewer moves closer, colors grow more saturated. Shadows along the artist’s cheek and forearm are revealed as solid blocks of candy-like pink, yellow and orange — variously suggesting pixels, Post-Impressionist pointillism and Ai’s long-running engagement with Pop Art.

Other recent acquisitions include “Eclipse” (2020), a digital print by Brooklyn artist Chitra Ganesh, which depicts two figures, possibly mother and daughter, standing by an arched window. The taller figure’s head consists of pink and red flowers framed by a translucent sphere resembling a moon. Like much of Ganesh’s practice, the artwork combines South Asian iconography with comics, surrealism, queer theory, Bollywood posters and speculative science fiction to foreground the perspectives of marginalized communities.

Jess T. Dugan’s portfolio of photographic portraits “Every breath we drew” (2022) represents inclusive notions of gender and sexuality, exploring the power of identity, desire and connection. Complementing these artworks are additional acquisitions by Buckminster Fuller, Sharon Lockhart, Tuan Andrew Nguyen and Rose B. Simpson, among others.