From Brazzaville, the Republic of the Congo’s capital city, Gary Weil, MD, travels inland by truck to Madingou. The distance is only 250 kilometers (155 miles), but the road conditions are poor. Deep ruts and churned-up dirt turn a trip of 2½ hours into seven. Weil says it is like “driving through chocolate powder.” He strains through the ubiquitous dust to see large trucks loaded with supplies, and often masses of men, careening in both directions. Such conditions cause vehicles to crash, overturn and, at times, plummet down cliffs. The drive is not for the faint of heart.

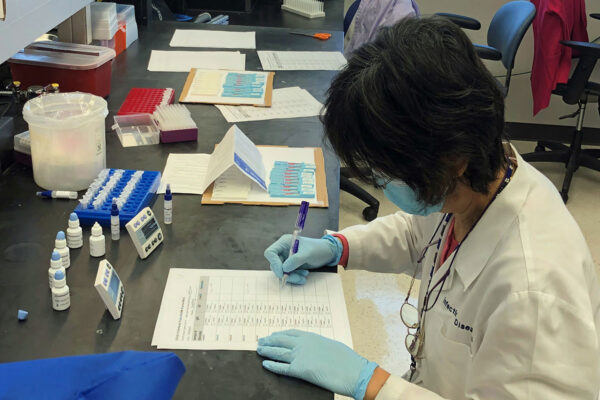

Weil, professor of medicine and of molecular microbiology at the Washington University School of Medicine, arrives safely in the small capital town of the Madingou District. His research team’s base camp is located here in Congo’s Bouenza region. A tiny laboratory within a small, tin-roofed hospital serves as a training facility for his French counterparts and in-country partners.

From Madingou, Weil and the team venture north to their field-study site. Along the way, the group must cross the Niari River tributary on a small barge. The flat-bottomed boat has no motor, so the ferrymen use the river’s current to guide the vessel back and forth from shore to shore. It can take 30 to 45 minutes to cross the slim waterway. Once on the other bank, the team resumes its journey, stopping at the third village, Séké Pembé.

At this rural site, researchers are conducting a multiyear study to determine whether a novel mass drug administration (MDA) program can effectively treat and ultimately eradicate certain worm diseases. Such parasitic diseases affect nearly 2 billion people and cause major disability for millions around the globe.

Considered “neglected,” these tropical diseases do not garner the same level of international funding as HIV/AIDS, malaria and tuberculosis.

“AIDS, malaria and TB are very serious global diseases, causing many deaths,” Weil says. “But in terms of numbers, many more people are infected with these helminth (worm) diseases, which cause chronic illnesses and disability — blindness and an inability to walk.”

Lymphatic filariasis (LF), for example, is a leading cause of disability worldwide and affects a reported 120 million people, with more than 1.4 billion people across 70-plus countries in tropical and subtropical regions at risk. LF, which is spread by mosquitoes, causes elephantiasis — massive swelling and deformity of the legs.

Another parasitic disease, onchocerciasis (oncho), also called “river blindness,” impacts 33 million people who live and work near rivers in sub-Saharan Africa. Spread by small black flies, oncho causes blindness and severe skin disease.

Weil has been studying these afflictions for decades. The road to progress has been long, but current MDA programs offer reasons for optimism.

“About 500 million people take these medicines each year, and the program is making good progress in many areas.”

Gary Weil

“In the case of LF, if 70 percent of the people take the free medicines once or twice a year for a period of five years, we can rid most areas of the disease,” Weil says. “About 500 million people take these medicines each year, and the program is making good progress in many areas. However, some countries have not started MDA programs yet, and some ongoing programs face significant challenges.”

One challenge is complications caused by loiasis, a third parasitic disease that is common in areas of central Africa. Medications for treating LF and oncho can cause serious adverse effects, including coma and death, in those who also have loiasis. Weil’s research team is investigating the effect of a novel treatment for LF that is safe to use in areas with loiasis.

An additional benefit of the MDA programs for LF and oncho, by contrast, is that the drugs used to treat those infections are also effective against intestinal roundworms, another public health problem in the tropics. Weil’s group is working to quantify this side benefit. Intestinal roundworms represent a formidable problem: Close to a billion people have giant roundworms, and 800 million and 700 million, respectively, have whipworms and hookworms. These soil-transmitted diseases cause severe anemia, and they impair growth and cognitive development in children, who are especially vulnerable to the effects of these worms.

The Séké Pembé study is part of a much larger global effort, the Death to Onchocerciasis and Lymphatic Filariasis (DOLF) Project, which is supported by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. The DOLF Project is part of the foundation’s program “to reduce the burden of neglected infectious diseases on the world’s poorest people.”

Weil serves as the DOLF Project’s primary investigator. His lab caught the attention of the Gates Foundation because of its three decades of research and field studies. In an early effort, for example, Weil and his laboratory created a novel test for diagnosing heartworms in dogs, which is a cousin of the parasites that cause LF and oncho in humans. This work led to a new diagnostic test for LF in humans that is now used around the world to map the disease and measure improvements related to MDA. Field-testing of the new tool led Weil to Egypt, where he and his collaborators worked for 20 years to nearly eradicate the disease in 2007, until political upheaval brought the project to a halt. Weil subsequently moved that field study to Sri Lanka.

Today, with a five-year, $13 million grant from the Gates Foundation, Weil manages teams and partners at 12 study sites in eight countries: five in Africa (Democratic Republic of the Congo, Ghana, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Republic of the Congo) and in Indonesia, Papua New Guinea and Sri Lanka.

“We started the DOLF Project in 2010,” Weil says. “It took us a long time to find the appropriate study sites and right collaborating scientists. Last fall, we requested supplemental time and funds for the project, and the Gates Foundation has agreed to an additional three years’ funding.”

The project’s objectives remain: 1. large-scale testing of alternative mass drug administration strategies with modeling and cost analysis; 2. randomized clinical trials with current drugs using combinations and schedules; 3. population-based studies to assess the impact of mass treatment programs for LF and oncho on intestinal worm infections.

Weil says progress is being made in all of the DOLF Project field-study sites, but the progress has been uneven. For example, one study in Liberia had to be halted for a year starting in early 2014 due to the Ebola outbreak.

“We regularly update stakeholders and share preliminary results with the World Health Organization, funding agencies, other technical experts and drug donors,” Weil says. “When we experience delays, they know why. And when positive results come in, we are able to help inform policy, and that’s what the Gates Foundation wants: to change the world through changing policy.”

New avenues open for change

As director of Washington University’s Institute for Public Health, William Powderly, MD, aspires to change the world as well. By design, Powderly, the J. William Campbell Professor of Medicine, also serves as director of the institute’s Global Health Center, which was formed to enhance and strengthen existing university research, as well as to increase its potential to improve lives. Powderly says Weil’s career path serves as a great model for the center.

“Gary Weil’s work started as very basic science — researching worms — and then it turned into discovering better diagnostics,” Powderly says. “Now he has taken a major lead worldwide in the treatment and eradication of filariasis, managing a global program funded by the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation.”

In hopes of replicating Weil’s model, Powderly — himself a specialist in HIV/AIDS and co-director of the Division of Infectious Diseases at the School of Medicine — works with others at the Center for Global Health & Infectious Disease, a subunit of the Global Health Center. He says that infectious disease research is a Washington University strength. Besides worm diseases, exceptional research programs focus on other parasitic diseases (leishmaniasis and schistosomiasis), malaria and tuberculosis, to name a few.

Regarding malaria, the World Health Organization (WHO) reports that 3.2 billion people live in areas at risk of transmission. In 2013, an estimated 198 million cases occurred with approximately 600,000 people dying, mostly children under the age of 5 in Africa. University scientist Daniel Goldberg, MD, PhD, professor of medicine and of molecular microbiology and co-director of the Division of Infectious Diseases, leads research examining the biology of the malarial parasite and its ability to resist current treatments. This research seeks to identify how the parasite secretes various proteins to affect red blood cells and reproduce. Novel findings are leading to new targets for drug development and new university and global partnerships.

Of note, Goldberg’s lab is collaborating with Joshua Swamidass, MD, PhD, assistant professor of pathology and immunology and of biomedical engineering, on antimalarial drug targets. With Lan Yang, the Edwin H. & Florence G. Skinner Professor in the Department of Electrical & Systems Engineering, Goldberg’s lab is working on malaria parasite visualization and detection.

Concerning tuberculosis, Powderly says that Christina Stallings, PhD, assistant professor of molecular microbiology, and Shabaana Abdul Khader, PhD, associate professor of molecular microbiology, are working on both new drugs for TB and new approaches to vaccines. “The research could be ready for human trials soon,” he says. “Shabaana Khader collaborates with institutions and organizations in South America, South Africa and India, and we would like to help them increase capacity by developing partnerships to conduct necessary field tests and human studies.”

In 2013, WHO reported that the mortality rate for TB had decreased 45 percent since 1990; however, TB still ranks as the second-leading cause of death from a single infectious agent after HIV. An estimated 1.5 million people died that year from TB, including 360,000 who were HIV-positive. Another 480,000 people developed multidrug-resistant TB, complicating treatment worldwide.

“The gross inequalities in health that we see within and between countries present a challenge to the world.”

William Powderly

Global health challenges of this magnitude are complex and systemic. “The gross inequalities in health that we see within and between countries present a challenge to the world,” Powderly says. “The conditions in which people are born, grow, live, work and age are at the root of much of these inequalities in health, and these economic and social conditions are relevant to infectious and noncommunicable diseases alike. Their resolution requires partnerships transcending the boundaries between disciplines.”

Along with assessing areas for synergy across the university, Powderly is surveying the 28 international institutions affiliated with the McDonnell International Scholars Academy (a Washington University program aiming to develop future global leaders) for areas of possible future collaboration.

“I have two goals in mind with this approach,” Powderly says. “One is potentially finding ways to increase the impact of research already being done here. The other is identifying areas where we can help partners build on their own capacity.”

Powderly stresses that the latter objective allows partners to frame the discussion, “stating what their problems, priorities and needs are.” Washington University could then determine if it has the capabilities and resources to assist in those areas.

“We typically come and go depending on the interests of our researchers, funding opportunities and other factors,” Powderly says. “If we help other global institutions build their own infrastructure — and ideally create an environment for ongoing collaboration — even as different investigators move on, we will have made a more sustained impact.”

With the university’s newest McDonnell Academy partner, the University of Ghana, Powderly hopes to build such a model from the beginning.

“In Ghana, for example, I may think that TB is very important because of its prevalence in Africa. They may decide that too,” Powderly says. “Or they may decide that a key priority is maternal mortality and safer labor. Another big, challenging issue, maternal mortality has many implications for families.” Therefore, fostering a partnership with Washington University’s obstetrics and gynecology department might be viewed by partners at the University of Ghana as more important than working with the infectious diseases division.

When university researchers go into other countries, Powderly says, they cannot assume persons in those countries haven’t been thinking about their own problems, and for a long time. “We cannot adopt a neo-Colonialist attitude that we know best. We don’t,” Powderly says. “It’s about listening and developing partnerships. And we want them to be sustained, and to have long-lasting impact.”

Helping Haitians help themselves

Lora Iannotti, PhD, assistant professor at the Brown School, knows first hand how important it is to identify partners for sustained impact. Having worked in Haiti for 25 years, she also understands what happens when short-team aid trumps long-term strategy.

“Many outside groups conduct their business without finding out if what they are doing is what the community wants or needs; then they leave,” Iannotti says. “This has wreaked havoc on the country.”

Through her multifaceted work, Iannotti collaborates with the Ministry of Education, the Ministry of Health and community health workers, as well as health-care workers within the health-care system. “I am adamant about this principle,” she says.

Her efforts in the country include conducting public health and prevention research projects, teaching U.S. students about public health interventions in resource-poor countries and working with a Haitian university to establish a higher education program in public health. This latest effort, she stresses, might be the most important collaboration Washington University cultivates for long-term health improvements in Haiti.

“Haiti has dire public health problems, yet the country has limited higher education in this field,” Iannotti says. “Basically, you have a small proportion of people who pursue medical degrees. They invest years and become trained to be doctors. Some will leave the country or work for international NGOs, and, generally, they do not focus their work on prevention.”

Determined to help remedy the situation, Iannotti worked with Washington University and Haitian colleagues to form an agreement with the Public University of North Cap-Haïtien (UPNCH). She found inspiration for the new program in U.S. history. “Looking at the Progressive Era in our country, the big changes in public health came from prevention: improving health by boosting living standards, cleaning up the streets, implementing vaccinations, etc.,” she says.

In July 2015, UPNCH and Washington University jointly offered a public health summer institute. Iannotti hopes the institute eventually leads to a full degree program. While raising funds, the collaborative team — including two School of Medicine faculty members and four representatives of the Brown School — is developing the curriculum and course work to that end. Iannotti says she is grateful for the support she has been receiving from colleagues and administrators. In particular, Brown School Dean Edward Lawlor, PhD, the William E. Gordon Distinguished Professor, has been a champion for university efforts in Haiti; he traveled there in summer 2014 to participate in Iannotti’s summer course, “Transdisciplinary Problem-Solving in Haiti: Public Health Interventions in Developing Countries,” and to visit research sites in Cap-Haïtien. At those sites, Iannotti investigates the relationship between poverty, micronutrient deficiencies and infectious disease, particularly in young children.

The biggest nutrition problem now, she says, is not a lack of calories, but a lack of particular nutrients. “Poor-quality diets, as in our country, lead to what’s referred to as ‘hidden hunger,’” Iannotti says. “A lack of certain nutrients — vitamin A, B12, choline, iron and zinc, for example — can increase the risk for morbidity, impaired cognition and mortality.”

These nutrients, not surprisingly, are found in eggs, fish, meat and milk, which are typically more expensive and less affordable in Haiti and other resource-poor countries.

“As a result, people are stunted or chronically undernourished. They become ill or die from diarrheal disease and respiratory infections because their immune systems don’t function as well without these nutrients,” Iannotti says. (Globally, lower-respiratory infections were the No. 2 cause of premature death in 2010, and diarrhea was the No. 4 cause.)

For one project, Iannotti partners with Patricia Wolff, MD, professor emerita of clinical pediatrics at the School of Medicine, to produce and distribute a fortified snack, called Vita Mamba, for impoverished school-age children. Wolff, another longtime devotee of the people of Haiti, is founder and executive director of Meds & Food for Kids, which produces ready-to-use therapeutic foods to treat malnourished children. Wolff’s factory in Haiti produces this new snack, which contains fortified peanut butter, soy powder and all the vitamins and minerals these children need for a day. The USDA Foreign Agricultural Service’s McGovern-Dole International Food for Education and Child Nutrition Program supports the project.

The research has shown significant improvements in children’s body composition with long-term implications for their health and development. Results will be reported to the U.S. Senate, together with those of other grantees, to help determine the composition of food aid commodities moving forward.

“It is important for us to further disseminate these positive results from the school snack,” Iannotti continues, “so that demand grows for the product and Meds & Food for Kids can build a sustainable business model.”

Another effort involves Iannotti; Zorimar Rivera-Núñez, PhD, assistant professor of social work at the Brown School; and Daniel E. Giammar, PhD, PE, the Walter E. Browne Professor of Environmental Engineering in the School of Engineering & Applied Science. Through the lens of their various disciplines, the team is assessing water contamination — beginning with toxic heavy-metal contaminants — and then determining as a group the impact of this contamination on nutrition.

In Haiti, 64 percent of the people do not have access to a latrine, and poor sanitation leads to unsafe drinking water. Further, certain water contaminants affect the absorption and metabolism of important micronutrients. The team plans to test microbial contaminants in future projects.

“Malnutrition — or any other global health challenge — won’t be solved unless we work across disciplines.”

Lora Iannotti

The project builds on Iannotti’s studies on nutritional outcomes in five Cap-Haïtien neighborhoods. Last summer, Iannotti, Rivera-Núñez, their UPNCH co-principal investigator and local university students determined the sources of water in these neighborhoods (government-built pumps and wells, community-built wells or family wells) and collected samples from each source, which Giammar is helping test. Where contamination is found to be higher, they’ll be able to target community development resources better and, ultimately, improve nutritional trials and other interventions.

“In many academic venues, but especially at Washington University, people are starting to talk about the importance of being ‘transdisciplinary.’ This approach is clearly what’s needed to address complex global health challenges,” Iannotti says. “Malnutrition — or any other global health challenge — won’t be solved unless we work across disciplines, try new methods and strive to find innovative and comprehensive strategies.”