On Sept. 28, 2018, Michael Loynd, JD ’99, stood proudly among WashU officials, local dignitaries and former Olympians as the five-ring Olympic “Spectacular” was dedicated near Francis Olympic Field.

As chairman of the St. Louis Sports Commission’s Olympic Legacy Committee, Loynd had worked years to ensure the 1904 Olympic games in St. Louis received proper due, and the ring sculpture – which has become a must-see photo op for students and tourists alike – was the culmination of that effort.

In doing so, he applied a lawyer’s tenacity to thoroughly understand every aspect of the 1904 games, including the athletes, nearly all of whom had been buried under 114 years of history. Until Loynd learned of Charles Daniels.

Daniels won the first-ever gold medal for U.S. swimming in Forest Park. But he did so much more, winning seven medals (four gold, one silver, two bronze) over two Olympiads, a record that stood more than six decades. In doing so, Daniels invented modern Olympic swimming and originated the freestyle stroke – the stroke every kid who jumps into a pool for the first lesson learns. And he did so with a white-collar criminal for a father and a mother who did everything she could to give her son a normal life.

“I was focused on getting the rings to WashU,” Loynd says. “I figured I might eventually write a paper or a short article about the athletes. And then I learned about Charles Daniels, and the more I dug into this guy, the more I was like, ‘I have to tell his story.’”

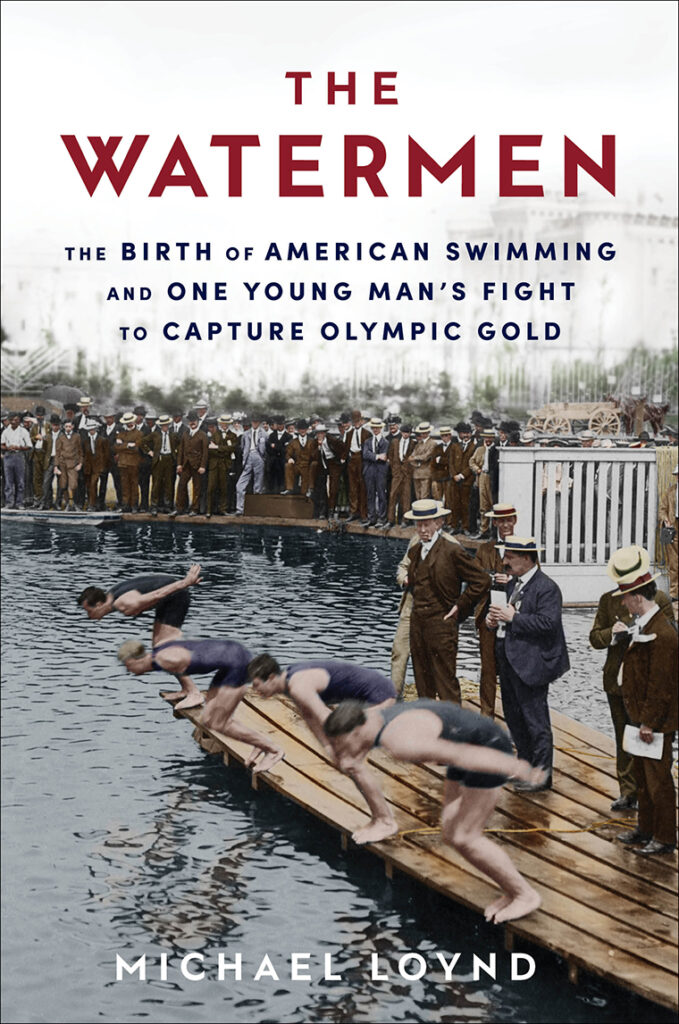

The result is The Watermen: The Birth of American Swimming and One Young Man’s Fight to Capture Olympic Gold (Ballantine Books 2022), a compelling tale of how U.S. swimming became an international power in the first decade of the 20th century and the band of upstart American swimmers who made it so. It’s also the story of one man’s role in it all, and how he influenced generations to come.

‘ … then I learned about Charles Daniels, and the more I dug into this guy, the more I was like, “I have to tell his story.” ’

Michael Loynd

Using that lawyer’s tenacity again, Loynd painstakingly researched Daniels — not only online but at points throughout the U.S. To write about Daniels’ childhood in Buffalo, Loynd visited Delaware Ave., the street on which Daniels’ family lived. Loynd made a trip to upstate New York to see the camp in which Daniels learned to swim. He met Daniels’ granddaughters in Wisconsin. He watched videos on swimming techniques, then got in the pool to try them out.

“I put my lawyer hat on for sure,” he says. “Because if you were presenting a case in court, you’d want to know every detail and anticipate every counterargument.”

The result is a 344-page nonfiction work that reads like a novel, in the same vein as Lauren Hillenbrand’s Seabiscuit or Stephen Ambrose’s Band of Brothers. “I love this story,” Loynd says. “It gives you a sense of empowerment. It gives you hope.”