In response to COVID-19, faculty members Jonathan Stitelman and Derek Hoeferlin of Sam Fox’s Global Urbanism Studio quickly pivoted not only their teaching model but also the very topic of study.

The city has changed. The city is always changing, but COVID-19 has accelerated the process. From New York and Hong Kong to Brisbane, Manaus, and Copenhagen, the pandemic is reshaping the ways we think about urban space.

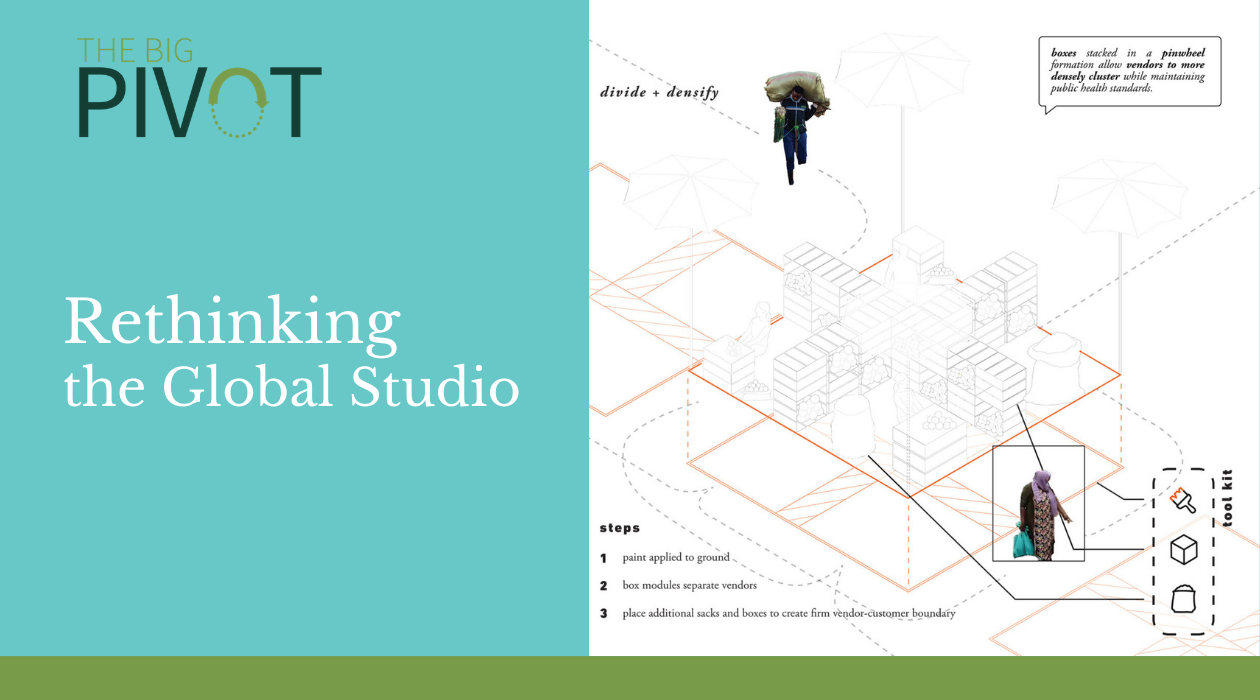

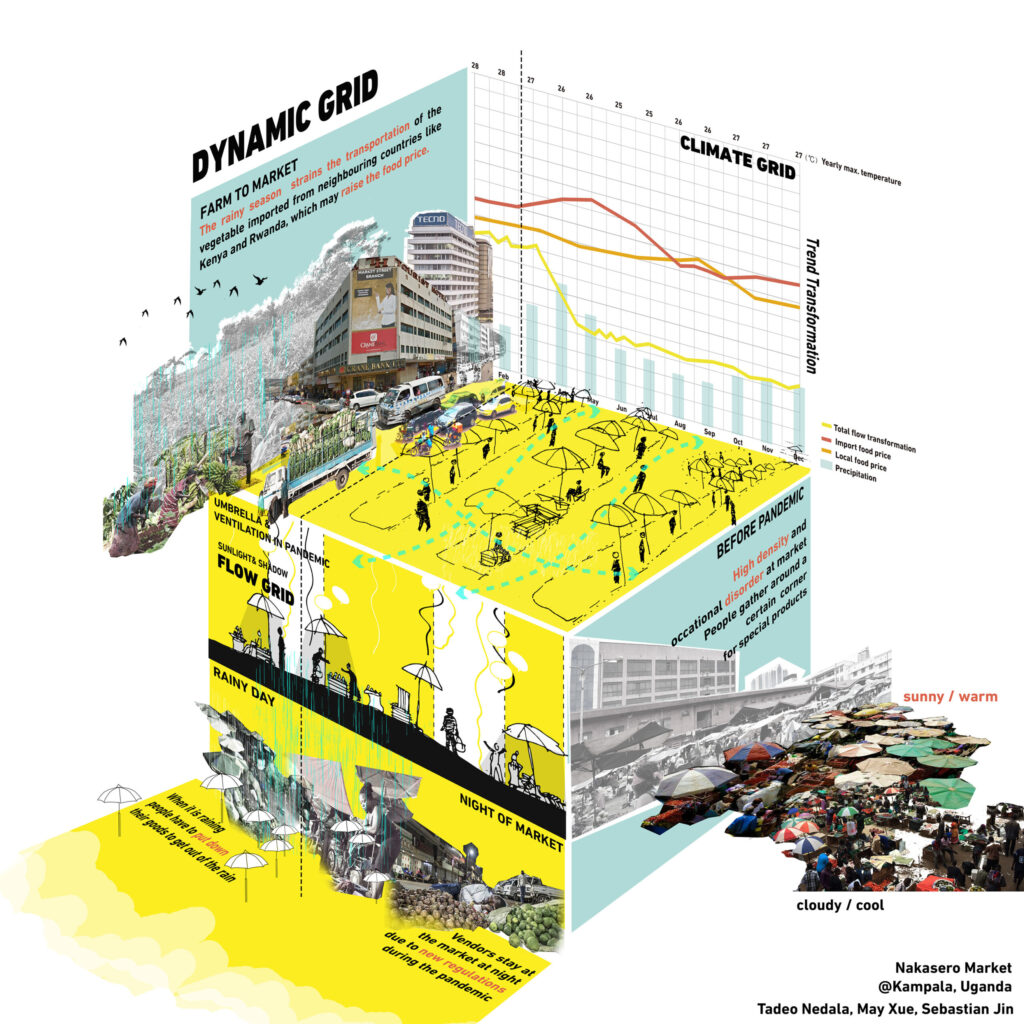

This past summer, visiting assistant professor Jonathan Stitelman led the Global Urbanism Studio, a 13-week program that allows Master of Urban Design students in the Sam Fox School at Washington University in St. Louis to study and work in major cities around the world. Stitelman had spent months organizing a partnership with Uganda Martyrs University in Kampala, but when the pandemic hit, travel was suddenly out of the question.

“The crisis forced us to shift to fully remote,” Stitelman said. “But in some ways, it’s been a blessing in disguise. It highlights the complexities of studying abroad, and provides an opening to think about the responsiveness of cities and the interconnectedness of global networks.

“In a matter of just two or three months, people completely transformed how they negotiate the city,” said Jonathan Stitelman, visiting assistant professor of urban design. “COVID-19 has impacted everything from restaurants and storefronts to expectations around homes, offices, and entrepreneurship.”

“How can cities be more proactive in responding to crises?” Stitelman asked. “After COVID-19, what does the future look like? And how can designers engage the globe itself as a place of inquiry?”

Hitting refresh

Launched in 2008, the Global Urbanism Studio explores commonalities among, and differences between, major urban centers. Under its auspices, scores of students have traveled to and spent months situating design proposals within Tokyo, Johannesburg, Dubai, Kampala, Mexico City, Shanghai, and Tijuana, among many significant world cities.

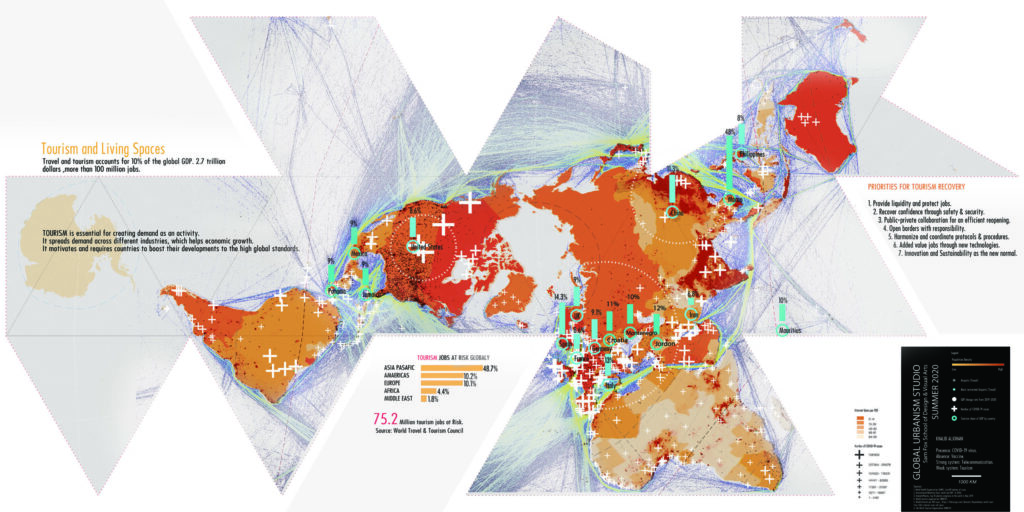

But in recent years, the rise of “on-demand” global supply chains and the paradoxical hardening of national borders had convinced Stitelman and Derek Hoeferlin, associate professor and chair of landscape architecture and urban design, that the studio needed a reboot. Rather than merely compare individual cities, could the studio specifically address social, cultural, and economic connections between them?

For Hoeferlin, a new approach began to crystalize last fall, during a global settlements conference in Ethiopia. “Right now, one of the main drivers of urbanization in African cities is Chinese investment,” he explained. In Addis Ababa, Ethiopia’s largest city, “It was eye-opening to see all the new bridges and skyscrapers, and all the signs written in Mandarin.

“That’s a very nuanced dynamic,” Hoeferlin continued. “But rather than retreat from it, I thought, that could be the theme for this year’s studio. What larger international forces are really driving urbanization today?

“And then COVID hit.”

Spaceship Earth

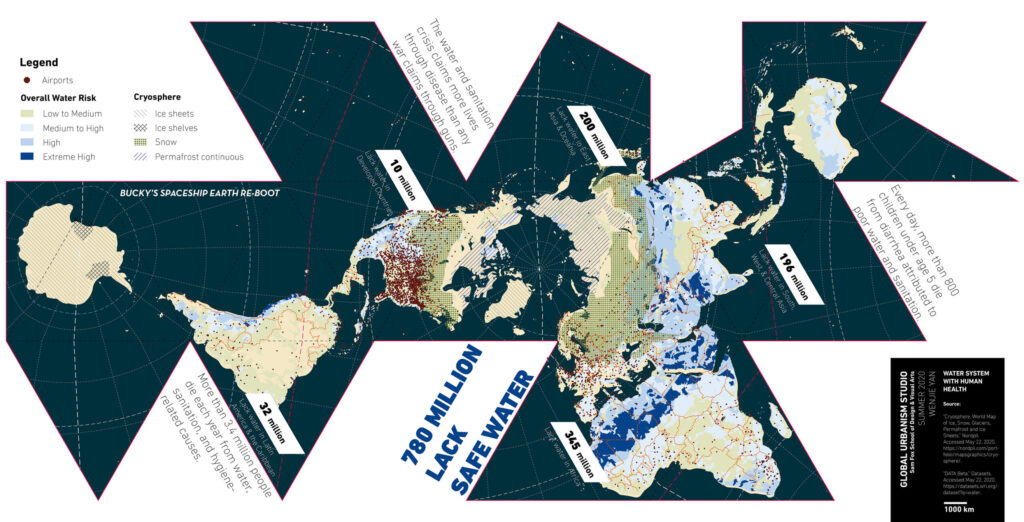

Hoeferlin and Stitelman quickly pivoted to building a remote studio. They drew particular inspiration from Buckminster Fuller’s famed Dymaxion World Map, which depicts all seven continents as a single island surrounded by ocean—a “deck plan… for Spaceship Earth,” as Fuller described it.

“Within two weeks, we’d mobilized 10 participants from across the globe,” Hoeferlin said. “Each guest ran either a one- or two-week workshop, and we asked them to address how their respective cities, or cities around the globe they are researching, were responding to the pandemic. What urban systems have proven resilient? What systems have been weaker than expected? How are they adapting to longer-term issues like climate change and systemic inequities?”

“Within two weeks, we’d mobilized 10 participants from across the globe.”

– Derek Hoeferlin

Students worked with Doreen Adengo, principal of Adengo Architecture, to examine the distribution of food, health care, and other resources in Kampala; with Patrick Gmür, partner at Steib Gmür Geschwentner Kyburz and former head of town planning for Zurich, to study a public market there; and with Marcus Carter and Michael Kokora—partners with OBJECT TERRITORIES, an architecture, landscape, and urban design firm located in New York City and Hong Kong—to explore spatial and formal densities in these two contexts. Other sessions led by Elisa Kim, founder of Atlas of the Sea, and Lola Sheppard and Mason White, partners at Lateral Office, explored design approaches to oceans and the Arctic, respectively.

A complete list of participants and recordings of select lectures can be found here.

“Pedagogically, it was different,” Hoeferlin said. “We had one-week or two-week shorts rather than one big project. It was an experiment, and we didn’t know where it would end. But a lot of our guests were already working in this format, and it’s become part of the teaching idea. For many years now, the practice of global design has already required remote interaction.”

Building a case

“For me, a good studio holds two things in tension,” Stitelman said. “To begin, I asked students to draw, at the scale of the Dymaxion map, what systems the crisis has revealed as strong or weak. And they could take different positions. Some students said public health is strong, some said public health is weak; others said logistics is strong, or logistics is weak. But they had to build that case through drawing.

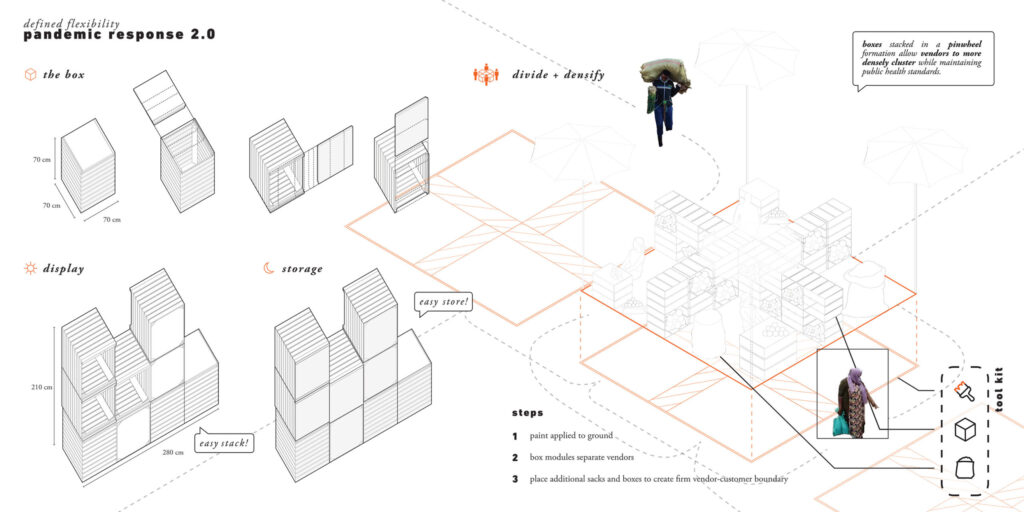

“The studio also burrowed down into a constellation of architectural spaces and elements—into a given city’s discreet spatial, material, physical qualities,” Stitelman continued. “The flexibility of cities is a great source of resilience. How as designers can we guide a conversation on those terms? How do we support vulnerable populations, or address historic challenges? Where are the friction points?”

“We start with the immediate crisis, but we also want to look at bigger systemic issues, like climate change, urban density, affordable housing and inequities. How do those need to be reassessed?”

– Derek Hoeferlin

“For architects and urban designers, the most successful projects are ones that enact change,” Hoeferlin added. “So you test out ideas and see what sticks.”

Located less than a mile north of Washington University’s Danforth Campus, the Loop is normally one of St. Louis’ busiest commercial districts. But COVID-19 closures hit the area hard. Additionally, in response to the death of George Floyd, and subsequent demonstrations against police brutality, many local shops and restaurants covered their doors and windows with protest-related signs and artwork.

“This was a moment to reassess everything around us,” Stitelman said. “How can designers engage with that process? That’s the research of the studio.”

Of course, the first step toward change is understanding conditions on the ground. Working under the (virtual) direction of architects Oliver Schulze and Mohammed Almahmood—respectively, founding partner and head of research & innovation for the Copenhagen-based firm Schulze+Grassov—as part of the “Lively Cities” workshop, the students spent hours cataloging the qualities that have made the Loop a successful public realm, and scrutinizing where improvements might be made.

“Students observed movement and social interactions; quantified pedestrian and vehicular flow; categorized stationary activity—sitting, standing, waiting, meeting; and documented the attraction points for visitors,” Stitelman explained. “Their findings help us understand how a design proposal might make the Delmar Loop more accommodating, comfortable, and resilient.”

Hoeferlin added, “The Lively Cities workshop challenged students, in a very short frame of time, to address what the pandemic and protests mean for future, democratic, equitable uses of public space and our collective rights-of-ways. Students realized that they probably won’t return to what they were before, or to a ‘new normal,’ but something different—and that’s probably a good thing.”

Days later, students presented their work as part of the Sam Fox School’s Lively Cities webinar. The online panel discussion, which is archived on the Global Urbanism Studio page, explored how social distancing practices are challenging conceptions of urbanity.

“We’re not going to ‘solve’ COVID-19 as an urban problem,” Stitelman concluded. “We’re just trying to look at it as an opening to think more freely about the future.”