Krister Knapp is a teaching professor and minor adviser in history in Arts & Sciences at Washington University in St. Louis. He teaches courses about conflict and security, including “The Cold War, 1945-1991” and “Hot Peace: U.S.-Russia Relations Since the Cold War.” He also coordinates the Crisis & Conflict in Historical Perspective series.

Why did Russia invade Ukraine? A short list of answers might include:

Restoring Russia’s Eurasian empire. Russian colonialism. Settling long-standing Russo-Ukrainian border disputes. Halting further NATO enlargement. Destabilizing the European security architecture. Repelling encroaching democracy. Detracting from domestic unrest. Solidifying power at home. Providing economic insurance. And defending Russian Orthodoxy against corrosive Western values.

Some of these respond to external threats (real or imagined), others represent internal challenges. All offer insight into recent Russian behavior. But they are only proximate causes.

The central reason underlying Russia’s invasion of Ukraine is Vladimir Putin’s perception of Russian security.

In the post-Cold War era, the gradual emergence of an independent Ukrainian identity has threatened Kremlin ambitions for a unified Slavic whole. Two democratic uprisings — the Orange Revolution in 2004 and Maidan Revolution in 2014 — loosened the Kremlin’s authoritarian grip on its neighbor. Left unchecked, such uprisings could spread to Russia herself.

This long has been one of Putin’s worst fears. In 2019, the election of Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky by 70% of the popular vote in a free and fair election further stoked that fear.

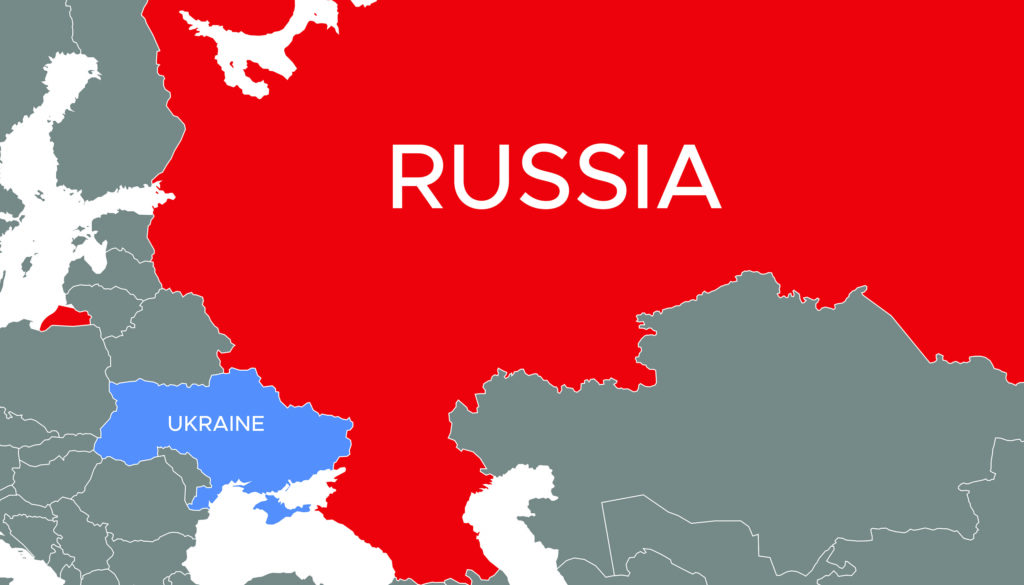

In the Kremlin, NATO enlargement — which the West sees as guaranteeing North Atlantic security — is viewed as “encroachment” on Russia’s western flank. Especially disconcerting to Moscow were the additions, in 1999, of the Czech Republic, Hungary, Poland, Bulgaria, Estonia and Latvia; and in 2004 of Lithuania, Romania, Slovakia, Slovenia, Albania and Croatia. Suddenly, NATO was at Russia’s western borders, with only Belarus and Ukraine separating it from New Europe.

Indeed, the collapse of the Warsaw Pact and the dissolution of the Soviet Union, in 1991, reduced what had been 15 Socialist Republics to a Russian Federation of just three new nation states: Russia, Belarus and Ukraine. The Russian empire shrank to its smallest size since Peter the Great’s rule in the late 17th and early 18th centuries, creating a de facto sense of Russian insecurity. Putin himself called the Soviet dissolution “the greatest geopolitical disaster of the 20th century.”

Russian domestic affairs also influenced the Ukraine invasion, albeit to a lesser extent. Internal unrest, political opposition and economic instability have plagued Putin’s two-decade rule. But these have waxed and waned. Alexei Navalny, Putin’s main political rival, remains jailed, and Navalny’s FBK (Anti-Corruption Organization) remains shut down. Dissenting journalists have disappeared. Old enemies, traitors and double agents have been assassinated with poison.

And until recently, Putin’s poll ratings were solid, the ruble was steady, and the economy reliable enough. The high cost of oil and natural gas insured a constant stream of petrodollars. Moreover, Putin has “sanction-proofed” much of the Russian economy by paying down its debt, investing heavily in gold, and parking his and his cronies’ money in hard-to-trace offshore accounts.

Now, war in Ukraine has dropped the ruble to historical lows. Average Russians will suffer and some individual sanctions will bite. But in the short run, the Russian economy is strong enough to withstand sanctions. War will continue unabated as long as Putin wants it to. Tanks shred paper documents. Sanctions don’t deter invasions.

Putin is surely concerned with internal threats, whether a palace coup or revolution from below. Still, he has enriched his brethren siloviki (“securocrats”) and sufficiently pacified his citizens that neither outcome seems likely. And if dissent grows beyond acceptable levels (a so-called “white” revolution), Putin has violently cracked down many times already.

Ultimately, it is the perception of Russian security abroad that most animates Putin’s decision-making. This has been apparent since his infamous 2007 Munich speech, which critiqued the U.S.-led international order. Subsequent actions have sought to control the post-Soviet space, or what Russia calls its “near abroad.” Russia attempted to quell democratic “color” revolutions in Ukraine (orange), Georgia (rose) and Kyrgyzstan (tulip), and exacerbated (or created) conflicts in the Nagorno-Karabakh region between Azerbaijan and Armenia; in the Transnistria region separating Moldova and Ukraine; and in Abkhazia and South Ossetia in Georgia.

The historic pattern is clear. By weakening newly independent states, Russia aims to stop them from joining NATO and the European Union. The willingness to invade should come as no surprise.

In the years since Munich, Putin has consistently signaled his intentions to protect what he sees as Russia’s interests — directly or indirectly, covertly or overtly, through force or through cyber and disinformation campaigns. Yet even stoking conflict in the Donbas region of eastern Ukraine failed to prevent Kyiv from drifting to the West.

Once all of Putin’s “hybrid” options had failed, a kinetic invasion became imminent.