Most people understand the idea of a university president or chancellor, but what exactly is a provost? The provost oversees the teaching, learning, research and scholarship at a university. When a school has a great entrepreneurship program? That happens with help from the provost. If a school emphasizes interdisciplinary research and coursework? That’s got the provost’s hand in it, too.

That hand is invisible to the average undergraduate or graduate student, and it certainly doesn’t act alone, but the provost has a major influence on what you learn and how you learn it. And in January 2020, Washington University got a new provost named Beverly Wendland, who is by any measure perfect for the job. A scientist who still loves the humanities, Wendland is able to find consensus in the diversity of needs and opinions at a place like WashU that has strong science, medical and engineering programs, as well as professional schools and robust humanities departments.

Wendland came from Johns Hopkins University, where she’d been the dean at the Krieger School of Arts & Sciences since 2015. There, she oversaw 22 academic departments, and her bona fides were well-established: She increased tenure-track faculty by 11 percent; she raised $747 million as part of a successful capital campaign; and she helped establish the SNF Agora Institute, a research, teaching and practice hub dedicated to strengthening global democracy.

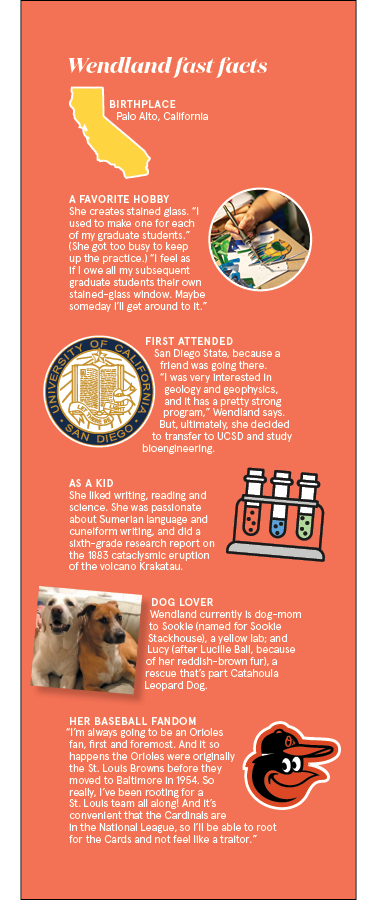

What initially brought her to academe, though, was science. A first-generation college student, Wendland studied bioengineering at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD) and neuroscience at Stanford University, where she earned her doctorate in 1994. She developed a lifelong interest in studying yeast during a 4 1/2-year postdoc and joined the Johns Hopkins faculty in 1998.

In January 2020, faculty and staff at WashU gathered in Holmes Lounge to meet the new provost. The mood of the event was optimistic, excited. But the next time the WashU community saw Wendland — whose first day wasn’t until July 1, 2020 — was on Zoom, and she was discussing fall plans for a pandemic everyone thought would have been over months before.

“I basically had to roll up my sleeves, jump in the pool at the deep end and start swimming,” Wendland says.

“But it allowed me to develop strong working relationships with everyone here. Instead of spending a lot of time sitting around reading reports, we actually got in there and got busy doing things together.”

— Beverly Wendland

Unsurprisingly the best way to meet Wendland would not be on Zoom but at a party where you could find out how a neuroscientist came to study yeast and what makes yeast similar to brain neurons. Or hear how a first-generation college student became a leader in academia. Or discover why she’s always going to be an American League fan in love with the Orioles, yet the Cardinals are finding their way into her heart.

The party may have to wait, but your introduction to Provost Wendland doesn’t have to.

You were the first in your family to graduate from college. What was that journey like?

My mother had gone to a junior college, and my father had a little bit of chemistry for a year. They valued education, but they didn’t have the whole picture of getting ready to go to college and applying to college and all of that. So I had to figure it out myself. A friend of mine, her mother actually helped me apply for my student loans. I feel like it’s a miracle I’m here.

How do you think your experience going to college impacts your leadership today?

It makes me an empathetic leader. I can relate to a lot of different circumstances and challenges.

How did you decide to go to grad school?

When I was at UCSD, I ended up doing a research-for-credit position in a research lab and enjoyed that. Also, I had a neurobiology course that showed me what the path is from an idea to discovery. I like puzzles, and this was a puzzle with real consequences. And in this neurobiology course, the professor told us about another professor at Stanford who had an idea about a molecule that organized [brain] synapses. He had designed some beautiful experiments that demonstrated the molecule had to exist. It made me want to do that.

So you knew you wanted to go to Stanford?

No, I applied to a bunch of programs in biology and neuroscience. I actually interviewed at WashU. But when I got into Stanford, I had the opportunity to work with the actual professor who had made me interested in graduate school.

From there, how did you come to study yeast?

Neurons are amazing cells. They are super complicated, very sophisticated, very intricate, very specialized. If you think about when something’s flying at your face, and then you blink your eyes, all of that happens fast because of the ways in which synapses and neurons are organized. They do their signaling in milliseconds.

When I was finishing up my graduate work, it was realized that yeast and neurons have similar proteins that are involved in secretion. Neurons use them to release neurotransmitters, yeast secrete enzymes for degrading sugars and other molecules. And the idea that there was anything similar between how a yeast would do secretion and how something as sophisticated as a neuron releases neurotransmitters was pretty mind-blowing. Going to work in a yeast system to try to understand more fully the intricacies of this process seemed like it would be an interesting move to make personally, because the experimental control available in the yeast system for designing and executing experiments was much more powerful than in mammalian cells (at the time). So I switched to yeast because I appreciated that they are actually much more sophisticated than people would give them credit for.

You joined Johns Hopkins in 1998. Do you remember the early days of being a professor?

I’m not going to lie: It was a lot of stress. But it was also very exciting. I got my first graduate student; I got undergrads who joined my lab immediately. One of them helped me finish my last paper from my postdoc, and she got to be an author on the paper with me. I got my first grant. I felt like within the first year, I checked off all the milestones. A couple of years after I’d started, I remember walking down the hallway, and this professor who’d just been hired was running down the hallway toward me, and I was thinking, “Thank God that’s not me.” But it brought me back to being a brand-new person in the department.

I know a lot of people deal with imposter syndrome even though they’re very talented and qualified. Was there any point when you first started at Johns Hopkins or later in your career that you experienced any imposter syndrome?

Sometimes I actually suffer from it even now. [Laughs.] I don’t know how much of it is being a first-generation woman, but I do feel as if I suffer from it less as I get older. So for any of our younger readers out there who suffer from imposter syndrome, take heart that it fades over time. If I feel some sense of imposter syndrome from time to time, I have a firm talk with myself, or I talk to my husband or to some friends who believe in me and can help me get over it, because it’s definitely a waste of time.

By 2019, you were dean of Arts & Sciences at Johns Hopkins University. What made you want to throw your hat in the ring to be WashU’s next provost?

I would get emails not infrequently from recruiters and generally ignore them because I wasn’t looking for a new job. But when I got this email, there was something that made me look into it more. I went to Chancellor Martin’s blog, and I know it’s going to sound cheesy, but it’s almost like the stars aligned in my head because he seemed like a person who would be really interesting to work for and that I could learn a lot from. And his priorities were things that I was familiar with from Hopkins. I felt as if I’d have something to bring with me to WashU to help him achieve his goals.

What was your reaction to getting the job? What were you most excited about?

I was excited about getting to know everybody here at WashU, developing myself to the next level of leadership and helping make WashU as good as it could be.

Then the pandemic started. What were some of the toughest lessons?

In a situation like this, where there’s changing circumstances, Chancellor Martin’s playbook is to try to delay your actual decision for as long as possible to allow as much information as possible to come in. It is smart, and we did that. But that was also hard, because everybody wants to know: What’s the plan? And then at some point, you have to make a judgment call. And it’s challenging to know when the time is right for that.

Has COVID significantly impacted the future of the educational experience at WashU?

In some ways, it’s a little too early to tell. I did appoint a Future of Instruction Task Force, and they helped us think through some of the lessons learned from the adaptations during this year-plus of COVID-impacted instruction. And there were definitely some things that we will be trying to carry forward. Doing a larger number of lower-stakes assessments throughout the semester, which is actually better for student learning, is one example. Faculty found they had a much greater uptake in attendance at office hours when they were doing them through Zoom. We’re not going to completely replace all office hours with Zoom, but we’d like to encourage faculty to offer both kinds.

Most people think WashU is a fairly decentralized institution. Have you found this to be the case? How do you think you’ll get more cooperation among the schools?

“WashU is definitely a decentralized institution, without a doubt. One of the lessons from the pandemic is the benefit of working together. In a lot of my conversations, people have indicated their desire to work together in a more facilitated way. I’m trying to structure the provost office to help make that happen.”

St. Louis and the region face a lot of challenges, similarly to Baltimore [where Johns Hopkins is located]. How much do you think WashU can do to improve the future of St. Louis?

When I think of St. Louis and Baltimore, challenges are not the first things I think of. The feature, I think, that is so palpable in both Baltimore and St. Louis is the creativity, the pride, the potential that resides within these cities that have this interesting mixture of people, opportunities and ideas. I really do see WashU as an institution that can attract amazing students, amazing staff, amazing faculty, and bring even more creative brain power to our city. I look for us to be attracting people who want to come here because we are in St. Louis. They want to be here; they want to contribute; they want to make a difference. Because if we can all work together and have high ambition, I think the sky’s the limit.

The university recently announced Gateway to Success — a $1 billion commitment to advancing our distinction in academics and student success. This is a huge commitment! What impact will this have on academics at the university? How do you think this will shift learning at the university as a whole?

“Gateway to Success expands our ability to attract and support the very best and most promising individuals at the undergraduate and graduate levels. Our students are remarkable. With additional financial aid resources, our student body will continue to grow in caliber and academic distinction. Not only will this growth enhance the classroom experience for students and faculty alike, it also will help us recruit outstanding scholars and scientists to WashU.”

A need-blind admissions policy allows us to focus on what matters: the academic potential, accomplishments and character of those who apply. It also sends a strong message that all qualified students are welcome in the WashU community. As a result, I anticipate that we will see significant growth in the applicant pool, which will include individuals who previously wouldn’t have considered applying. As the number of applicants increases, the quality of the students and diversity of the applicant pool will increase as well. We will be able to admit talented and promising students from all walks of life, representing a broad range of backgrounds and socioeconomic classes. Elevating diversity enriches the student experience and the WashU community for all. A need-blind admissions policy exemplifies our core value of creating an inclusive campus environment that is welcoming, nurturing and intellectually rigorous.

I know faculty diversity has always been important to you. Why do you see it as important, and what is WashU doing to improve in this area?

Trying to recruit from a very restricted pool of applicants, you’re missing out on a whole host of talent, whether it’s students, faculty or staff. Plus, there is so much evidence out there that better decisions are made and better progress is made when you tap into a wide range of perspectives. If you’re restricted to a monolithic, homogeneous set of inputs, you are not going to get the best output possible. That’s why it’s so important.

So what are we doing? One of the things that I’m very excited about is our WashU Equity and Inclusion Council [a university-wide body that is creating accountability and structure around equity and inclusion at the institution]. I think that is an important body that is going to help the whole institution keep our focus on equity and inclusion. I’m excited to support Kia Caldwell in her new position as vice provost for faculty affairs and diversity. We’re also working on several grants that will help us keep making progress on hiring and setting up structures institutionally that will help support the success and the accomplishments of all our faculty.

You’re a scientist and you also love the humanities. Why do you think they’re important?

“The critical foundational skills that the humanities teach our students are fundamental and enduring. Training in the humanities facilitates understanding differences, engagement with others, reflecting on and acting within ethical frameworks, and asking important and deep questions: What are rights? What are our obligations to one another? How do I fit in with a community?”

We are a university. We’re training students who are going to be leaders in the world, who are going to be able to be responsive to whatever the world throws at them. And the humanities are a fundamental component of training students in their ability to do all that.

WashU is in the midst of a strategic planning process. Where do you hope the university will be in 25 years?

Since the planning is still ongoing, it’s difficult to say for certain what our goals will be, but I hope that the reputation and stature of WashU will have risen significantly. Also, by then, I hope we’ll be known nationally as the leader in educational access for students from under-resourced backgrounds, and we’ll have achieved our goal of providing the very best opportunity for each and every one of our students to thrive and prosper, regardless of their background. And I hope that we’ll have contributed to making St. Louis an even stronger and more vibrant city.

Every day, women are expanding boundaries, pushing forward and showing up in the areas of scholarship, academia, and research. And when that happens, we are all better for it. Wendland is one of many remarkable women at WashU who are showing up with grace and leading the way. READ MORE.