While in the graduate program at Washington University, Kahlil Robert Irving, MFA ’17, crafted hundreds of black glazed ceramic pieces as part of a series of work called “Undocumented.” When he had 49 made, he created a piece called “49er’s (Dead Soldiers).” He recombined them into another piece, “ConcernedStudent1950: Or The Johnson Family Reunion” when he had 79 of them made. With 250 pieces, he put them on two ten-foot-long tables and titled it simply “X.” “Before and After Sundown, Town” was the piece he made with the vessels when he had around 400 pieces. He was recalling the Jim Crow era when being Black and in certain spaces after sundown meant violence. In this piece, the black vessels represented black bodies.

“The vessels, like black people themselves, are visible and vulnerable entities,” wrote the Riverfront Times. “They are Black men and women passing through sundown towns. They are communities rejecting segregation amid an ocean of angry white faces.”

In 2020, Irving reshaped the piece again this time into “My Grandmother’s Cupboard (Artifact),” which will be on display at the High Museum in Atlanta as part of the What Is Left Unspoken, Love exhibit from March 25-August 4, 2022. In it, Irving is inviting his ancestors to the table.

“I’m thinking about the generations of my family and if we could all eat together in one place,” Irving says. “These are black-glazed containers and crocks that we would cook food in, and plates that we would eat the food from, and serving dishes that would serve the greens, the pigs feet, the soup, the salad. It’s a metaphor for all of my generation and all the generations before me.”

Irving has been thinking a lot about time. He recently moved back to St. Louis after working in New York and Illinois, to care for a sick relative. Irving was born in San Diego, but grew up partly in St. Louis. Here he first learned pottery when his father took him to a class at the now defunct Potters Workshop. Irving spent weekends in a high school art program at the pottery wheel. A mentor told him he should consider college, so he applied to the Kansas City Art Institute and was awarded a full scholarship in 2010. It was there that he started thinking about what it meant to be an artist.

“I think making art is a way to confront the questions and the challenges that we face, and specifically what Black folks face,” Irving says. He sees his art as a way to turn an experience around and show it to the perpetrator, telling them, “This is the way it is, and you can’t see it, even though it’s right in front of you.”

After earning his BFA, many of Irving’s mentors suggested he go to graduate school. He was awarded a Chancellor’s Fellow to study at Washington University and returned to St. Louis. His experience wasn’t always easy.

“I was one of three black people,” he says of his first year in the program. “And then I was one of two.” But he found solace in the community where he organized exhibits and projects. He was even featured in the Riverfront Times.

Right after graduation, Irving was invited to a group exhibition at Callicoon Fine Arts in New York and then got a solo show, propelling him onto the national stage. He is included in the Whitney Museum of American art’s collection exhibition “Making Knowing: Craft in Art 1950–2019” and now has two works as part of the museum’s permanent collection.

“I think making art is a way to confront the questions and the challenges that we face, and specifically what Black folks face.”

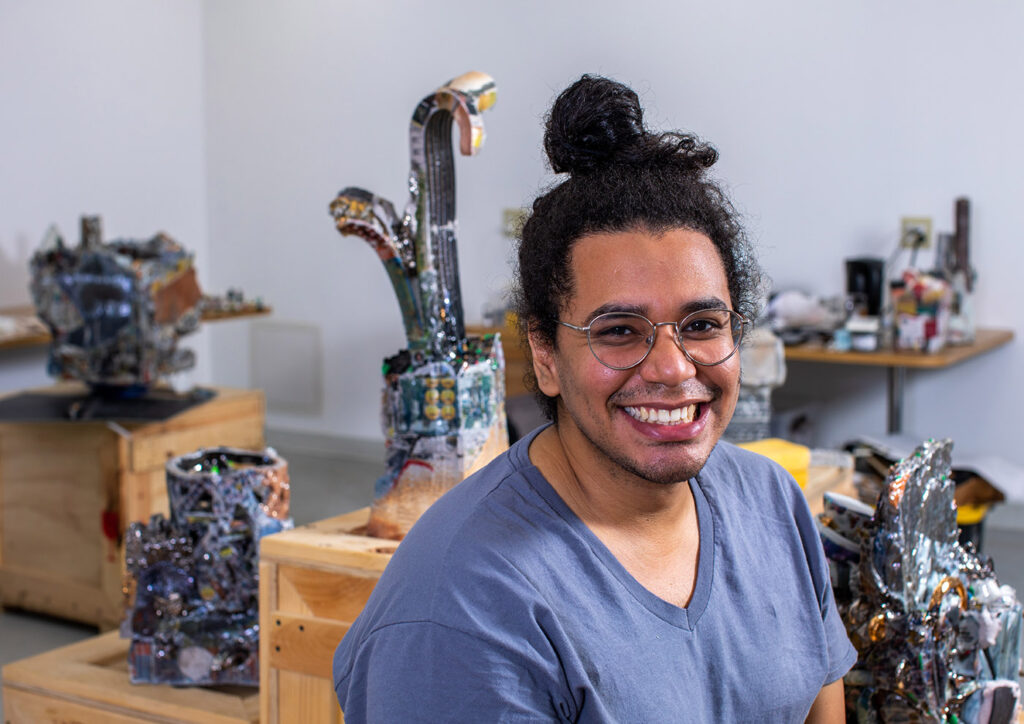

Kahlil Robert Irving, MFA ’17

The work at the Whitney is not related to his “Undocumented” series. It is another series of work Irving creates that looks more like assemblage art — there are bits that look like Styrofoam and paper, for instance — but it is all actually ceramic. In one piece, for instance, he combines what looks like broken pieces of ceramic and twisted rebar and adds “I AM MIKE” or “NO CHARGES FOR WILSON,” commenting on the case where white police officer Darren Wilson shot and killed Mike Brown, an unarmed teenager. Another piece has the acquittal documents for Jason Stockley, the police officer who shot and killed Anthony Lamar Smith in 2011, imprinted on them.

“In undergrad, I learned different industrial practices that I could use, not at an industrial level but at a one-to-one level in my own studio. And it allows me to work in the trompe l’oeil, this theater of representation that is not in the real,” he says.

His work was also part of the Great Rivers Biennial at the Contemporary Art Museum of St. Louis. The program awards three artists $20,000 and a major exhibition at CAM. His exhibit, “At Dusk” featured murals, flags, and his “assembled” ceramic sculptures that seemed to include broken bits of fancy dishware and molten metal fragments all melded together. Irving has an exciting fall and winter with many exhibitions to come (see sidebar). That was a good welcome back for Irving, who bought a studio space in South St. Louis and wants to start growing his own food on the property. “Not only is my practice creating art,” he says, “but also can I do things that can truly help make a difference in people’s world and people’s lives