Gun violence in the United States has reached crisis proportions. Nearly 40,000 people are killed by guns in the United States every year and another 175,000 are wounded. Women and individuals of color are disproportionately affected. Mass shootings occur with alarming frequency in schools, in offices, at churches and concerts, and in theaters. An average of one school shooting occurs every week.

Although Americans constitute only 4.4% of the world’s population, 42% of civilian-owned guns in the world are found in the United States, and our rates of gun deaths (both homicide and suicide) greatly exceed those of other industrialized nations. The U.S. gun violence crisis has spilled over the border: More than 200,000 guns are smuggled into Mexico each year, and the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime report that easy access to guns is the major contributing factor to high gun-related homicide rates in Latin America.

Yet the crisis continues to spiral out of control.

In 2017, Professor Leila Sadat, as the director of the Whitney R. Harris World Law Institute at the School of Law at Washington University in St. Louis, launched the Gun Violence and Human Rights Initiative to tackle this problem. Co-author and Harris Institute Senior Fellow Madaline George, JD ’14, and a team of law student researchers worked with the Institute for Public Health’s Gun Violence Initiative to explore this question from a human-rights perspective. We have held conferences and expert meetings, published our findings, testified before international human rights bodies, and helped to reframe of the policy and legal debate. We recently received funding from the Joyce Foundation to support work on implementation of our findings in the courts.

Several takeaways have emerged from our work.

First, easy and unregulated access to firearms, as well as the potency of weapons such as the AR-15, are the sources of the problem. As Philip Alpers, founding director of GunPolicy.org, has observed, the gun is to gun violence as the mosquito is to malaria. It is the vector of the disease. While mental illness is sometimes invoked as the chief culprit, not only is there little evidence that this is correct, but the United States does not appear to have higher levels of mental illness than other countries, underscoring that it is easy access to guns, not mental illness, driving our high fatality rates.

Second, gun-safety laws work. Many countries have implemented strict firearm regulations in response to mass shootings and public safety concerns, and they have uniformly seen reductions in gun violence. Similar findings emerge when comparing U.S. states with comprehensive gun-safety legislation to those without it. Research shows that universal background checks, licensing for gun possession and firearm dealers, safe-storage laws, restrictions on the sale and possession of high-capacity and semi-automatic firearms, and waiting periods can dramatically reduce firearm homicides, suicides and accidental deaths.

Third, although gun advocacy groups often argue otherwise, gun-safety laws are constitutional. In 2008, a divided Supreme Court, in District of Columbia v. Heller, held for the first time that “the Second Amendment conferred an individual right to keep and bear arms.” The Court added, however, that this right “is not unlimited.” A study of more than 1,150 challenges to firearm regulations in the decade after Heller found that the laws — including assault weapons bans, mandatory background checks, safe storage requirements and waiting periods — were constitutional over 90% of the time. The United States’ fascination with “gun rights” as constitutional rights is not only new — it is exceptional. Only two countries have a version of the Second Amendment comparable to ours, and both emphasize that the right is subordinate to government regulation.

Our work establishes that gun violence interferes with Americans’ enjoyment of fundamental human rights that are found in treaties and customary international law. These include the right to life; the right to security of person; the right to be free from torture and ill-treatment; the right to health; the right to an education; the right to freedom of association and peaceful assembly; the right to freedom of expression, opinion and belief; the right to freedom of religion; the right to freedom from discrimination on the basis of race or sex; the right to a standard of living adequate for health and well-being; the special protection afforded to children under international law; and the right to participate in the cultural life of the community. They also infringe on the right to vote and participate peacefully in the political process.

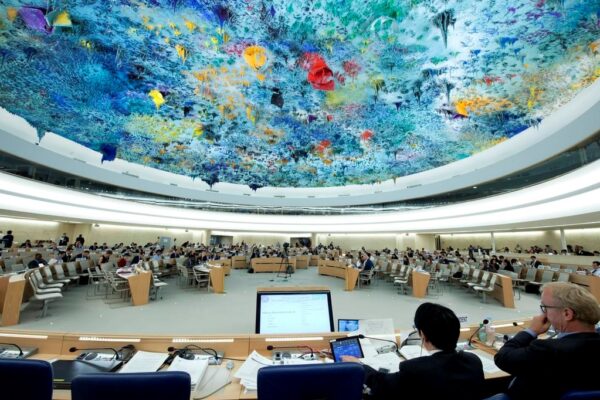

The failure of many states and the federal government to adopt gun-safety legislation to prevent gun violence violates a legal obligation to protect the human rights of Americans. The U.S. failure to act has been the subject of comment and review by the U.N. Human Rights Committee, the Human Rights Council, the Committee Against Torture, the Committee on the Elimination of Racial Discrimination and the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights. Responding to the crisis requires getting the political branches to take human rights seriously and to adopt public-health measures addressing the problem. It also requires a cultural shift (that is already underway) to focus less on gun rights and more on human rights. Until we do, American exceptionalism will literally kill us, as fatalities from gun violence continue to rise.