As a hospitalist and instructor in medicine, Han Li, MD ’15, sees a bit of everything, but she has always found infectious disease fascinating. Plus, she was born in China, and her grandparents are still there. So she began following the COVID-19 outbreak in early January, and she was stricken by the death of the ophthalmologist who had sounded an early alarm, only to be rebuked by the government. When word came of the first possible COVID-19 patient at Barnes-Jewish Hospital (BJH), Li volunteered to take care of them.

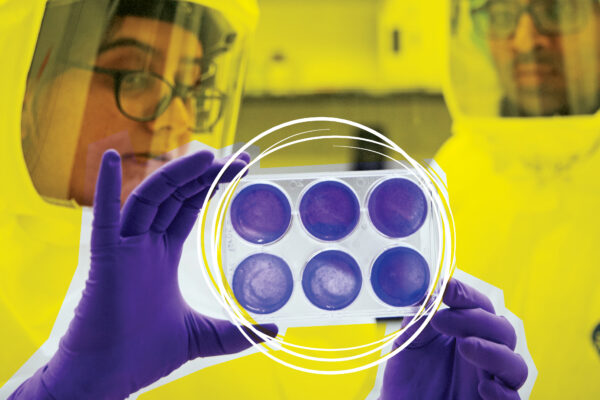

Even donning the PPE was stressful at first: “‘OK, I’m going to use hand sanitizer, put on my mask, use hand sanitizer again, put on my goggles — oh, did I touch something else?’ It was nerve-racking.” But with practice, like any motor skill, it began to feel natural, and when no one became ill, Li’s confidence in the PPE was bolstered. “The COVID floors might be the safest place to be,” she says.

By now, she has treated several hundred patients. The symptoms are a dizzying array: Some patients tested positive with zero symptoms; some had isolated GI symptoms or only cognitive symptoms, which made more sense as physicians realized the virus could cause microclots anywhere in the body. To provide guidance for taking care of these patients, Li created the “COVID-19 Hospitalist Manual,” a collection of clinical information developed by multidisciplinary teams at BJH. Dialysis, for example, would be done in COVID-19 patients’ rooms, as per the protocol recommended by Anitha Vijayan, MD, professor of medicine. For patients in psychological distress, who would need someone in the room 24/7, Li worked with others to implement the usage of baby monitors, so the sitter could be right outside the door.

Initially, tests were hard to come by, and samples had to be sent out, but the microbiology lab and hospital epidemiologists quickly developed their own assay. For peak caseloads, five of the seven ICUs were converted to COVID-19 care, and the observation floor became the cardiac critical care unit. “It was musical beds,” she says wryly. “So many departments had to work in lockstep.”

By early June, “we were almost in single digits,” she says with a sigh. “We are ramping back up, but now we know how to take care of these patients and have treatments I have seen help patients improve.”

With remdesivir and dexamethasone especially, “we can take them off oxygen within a few days,” she says. “Previously, they would have rapidly decompensated.”

Li has also now discharged a few patients who were critically ill in the ICU for weeks, but improved with treatment. “I remember one patient who cried the day I told her she could go home, because she didn’t think she was ever going to. That was very rewarding and reminded me of all the progress

we’ve made.”