On Election Day in 2008, Gena Gunn McClendon, project director with the Center for Social Development (CSD), volunteered with CSD colleagues at a polling place in Jennings, Mo., a predominantly Black community just north of St. Louis. They were stunned by late openings at polling places and the long lines. People waited for hours to vote.

“Voters did not stand in line for hours where I lived,” McClendon recalls. “I saw the lines and thought, ‘This is unacceptable.’”

As a result, in 2017, the Center for Social Development started a new initiative, Voter Access and Engagement (VAE). “We had several questions,” McClendon says of starting VAE. “Are voters engaged? If not, why not? Do people in lower-income communities have fewer opportunities to vote? Are voting conditions equitable?”

On Election Day in 2018, McClendon dispatched 38 graduate students to observe 20 polling places across St. Louis City and St. Louis County. The sites were in low- and high-income neighborhoods, and with majority-white or majority-Black populations. VAE researchers found that living in low-income, predominantly Black communities was associated with long voting lines, late polling place openings, broken machines, poor polling-site accessibility for people with disabilities, and insufficient signage outside polls.

“When that happens, is it intentional?” McClendon asks. “Probably not.” For instance, Missouri law demands that every polling place have an election judge from each political party. If one party isn’t represented, the polling place must shut down until a judge from that party arrives. McClendon points out that residents in St. Louis City and northern portions of St. Louis County tend to be Democrats, and election authorities have trouble recruiting enough Republican judges.

These circumstances can affect voting outcomes. “In 2008, Barack Obama lost Missouri by fewer than 4,000 votes. If you factor in late openings of polls, broken voting machines, and long lines that discourage voting, you have to wonder whether Obama could have won Missouri.”

To raise awareness about the problem, VAE published its findings in “Will I Be Able to Cast My Ballot? Race, Income, and Voting Access on Election Day.” McClendon has spoken to students in local high schools, organized a film festival, and held multiple screenings of Rigged: The Voter Suppression Playbook, which documents voter-suppression tactics used in several states, including Missouri.

McClendon noted some progress. Missouri’s voter ID law disproportionately affects low-income, elderly and Black voters, who are less likely to have state-issued identification. In a small but hopeful step, a recent court decision threw out the requirement that voters sign a sworn affidavit if using non-photo identification to vote.

Despite this positive step, barriers remain, she says. Missouri does not offer early voting, same-day voter registration, or no-excuse absentee balloting — all of which could improve voter access and engagement, especially in the time of a global pandemic.

This year, thanks to voter advocates and lawmakers, Missouri expanded the absentee and mail-in voting options for the 2020 Election season due to risks related to COVID-19. But there are still shortcomings with casting an absentee or mail-in ballot. “For instance, if voters fail to sign the back of the envelope, or do not check a small box on the preprinted return envelope confirming their current address, then their ballot can get rejected,” McClendon says. And the new law requires a notarized affidavit for all mail-in ballots and all absentee ballots unless the excuse for voting absentee is medical. For some voters, identifying a notary is difficult.

The process of applying for, receiving, and returning the ballot to the Board of Elections with the postal service can take 30 days or more, and in many instances, the voter never receives the ballot. All of these challenges make it difficult to cast an absentee ballot successfully.

“People shouldn’t have to go through so many barriers to vote,” McClendon says. But she adds, “while the system isn’t perfect, it works well for most voters and poses less risk of exposure to COVID-19 than in-person voting.”

McClendon works with the County Board of Elections as part of her project with the VAE. This month, she joined the League of Women Voters volunteers to assist the Board of Elections with the August 4 primaries. In this role, deputized volunteers called voters whose cast ballots had been rejected, and told them how to correct it.

St. Louis County election officials relaxed the notary requirements for absentee ballots received from voters 65 years and older. “While the decision to relax the notary requirement for the elderly was a positive for many absentee voters, unfortunately many of the ballots were [still] rejected for multiple reasons,” she says.

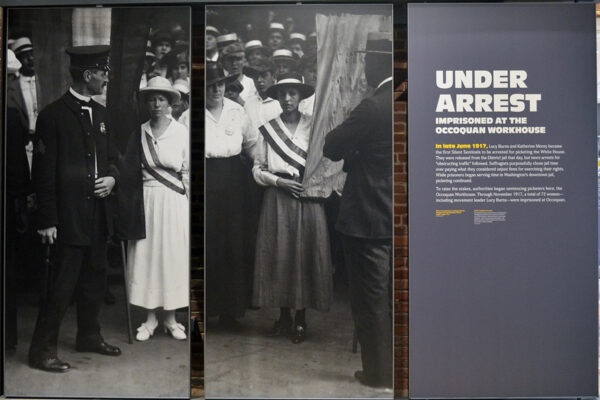

Despite everything, McClendon says she is cautiously optimistic. “I have to believe we can have fair elections, or I could not continue to do this work,” McClendon says. She reflects on the loss of U.S. Rep. John Lewis. Many of the stands he took during the civil rights movement, and throughout his congressional career, were to ensure that the right to vote was protected for all Americans.

“If John Lewis could endure being beaten and arrested dozens of times in order for us to vote, then the least I can do is vote, and try to clear a pathway so others can vote,” McClendon says.

She hopes to continue studying and raising awareness about voter suppression in Missouri. VAE is working on two new studies: one on voting conditions and voter turnout, and another on how race, income and turnout are related.

“I don’t want to leave the world in this situation,” McClendon says, “where there’s a threat to democracy for our young people. It’s not fair. People fought for me, and I need to fight to make sure everyone can vote.”