What do you do when your government lies?

In “Dateline-Saigon,” a new documentary about journalism during the early years of the Vietnam War, a tight-knit band of future Pulitzer Prize winners learns the simple, if not easy, answer: You tell the truth.

The film, some 12 years in the making, was produced by Richard Chapman, senior lecturer in film and media studies in Arts & Science at Washington University in St. Louis. Chapman previously produced the HBO feature “Live from Baghdad,” about reporting during the Gulf War.

In this Q&A, Chapman discusses “Dateline-Saigon,” the dangers correspondents faced and lessons for contemporary reporters and readers.

Describe ‘Dateline-Saigon.’ What’s it about?

This is the origin story of the war. The film begins in 1960, when U.S. involvement was ostensibly just in support of the South Vietnamese government. It ends around 1964, after Kennedy was assassinated and Johnson began pouring in troops.

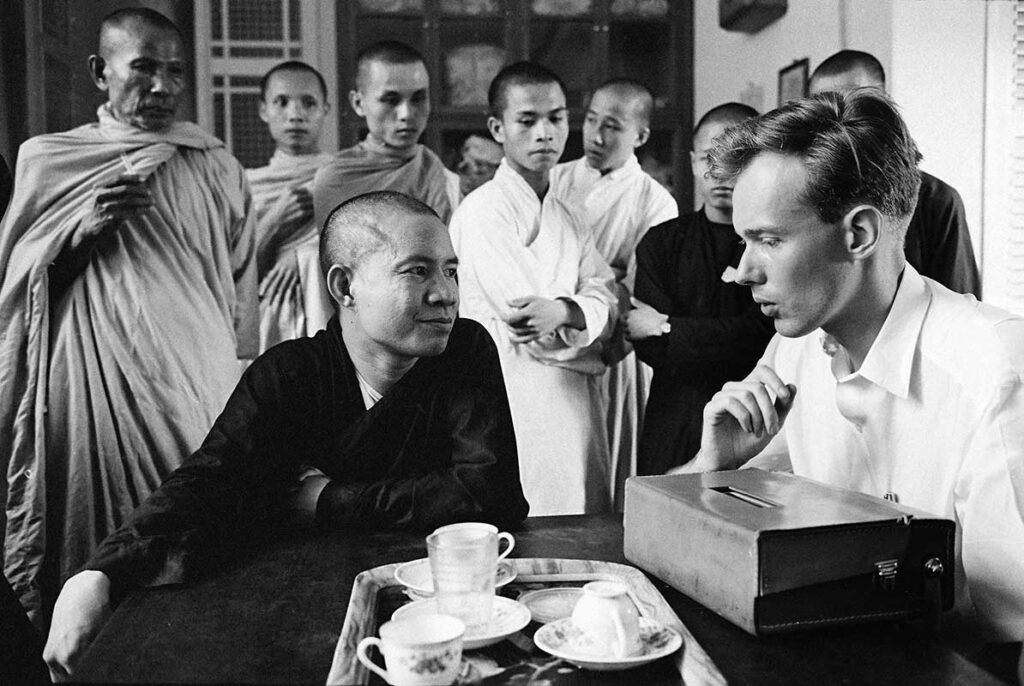

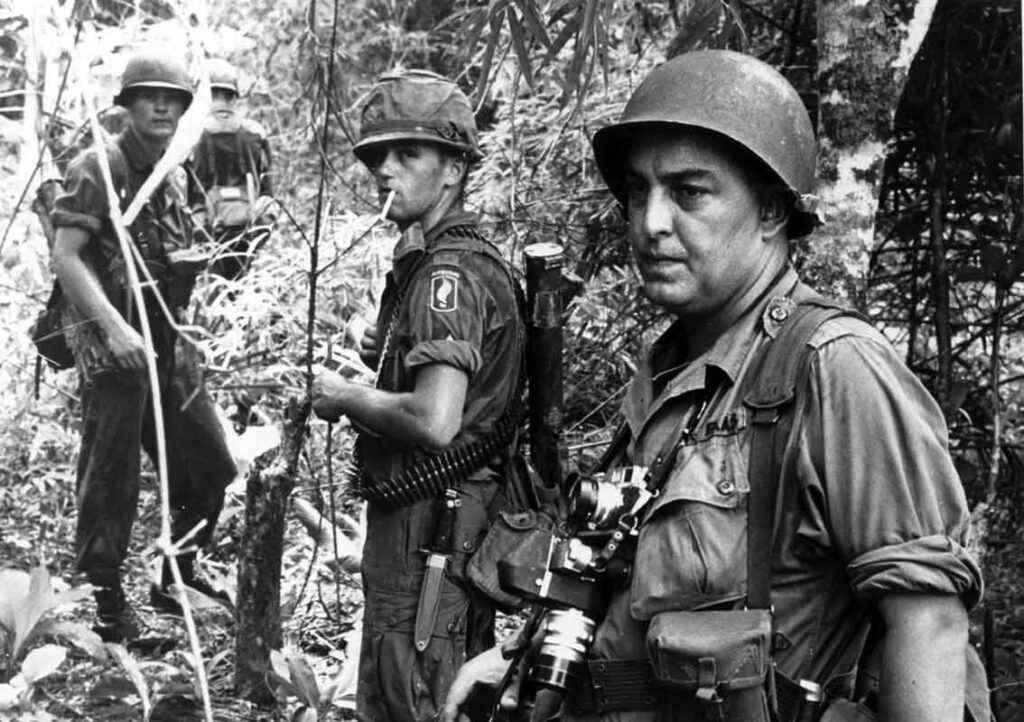

The film is largely built around interviews with five reporters: David Halberstam of The New York Times, Neil Sheehan of United Press International, and Malcolm Browne, Peter Arnett and Horst Faas of The Associated Press. Other people floated in and out, and there had been previous reporting on the French conflict. But in the early years of American involvement, these guys essentially owned the story.

The relationship between the press and the Pentagon would become highly contentious. Did it start out that way?

Not at all. These were Cold War kids. Their mentors were World War II reporters, like Ernie Pyle. They had patriotic fervor. They were looking for adventure. They came in with their minds right. They wanted it to work.

But pretty quickly they began to realize that the government was lying to them. Malcolm Browne stepped off the airplane in a wool suit. Shortly thereafter, he notices an aircraft carrier steaming up the Saigon River. He asks the American military attache about it. The guy just looks at him. “What aircraft carrier?”

So despite being competitors, they kind of banded together. They had to. No one else was helping them.

And yet the military allowed correspondents relatively free rein, in terms of where they could and couldn’t go.

Yeah. Go where you want, do what you want, record our heroism in saving this little country from the threat of Communist domination.

In those days, you could still take a taxi out to the battlefield. So one day, they did. And what they saw was miserably at odds with the official story. The military was reporting 100 Vietcong killed and maybe five casualties. In fact, they’d killed 13 Vietcong; the rest of the dead were American-allied South Vietnamese forces.

Another turning point was Browne’s “Burning Monk” photo (which captured the self-immolation of Thich Quang Duc in 1963). That was the first time they said, ‘Wait a minute. Not only are we prosecuting the war poorly, but there are real moral issues with supporting a corrupt government that doesn’t represent the Buddhist majority.’

By the time of the Gulf War, which Arnett also covered, things were totally different. Reporters were embedded with carefully selected combat units and used as attempts at thinly veiled propaganda and news management.

What surprised you most?

“‘Dateline-Saigon’ captures a swirl of personalities and conveys the excitement of reporting in a fast-moving, confusing and dangerous atmosphere.”

– The New York Times

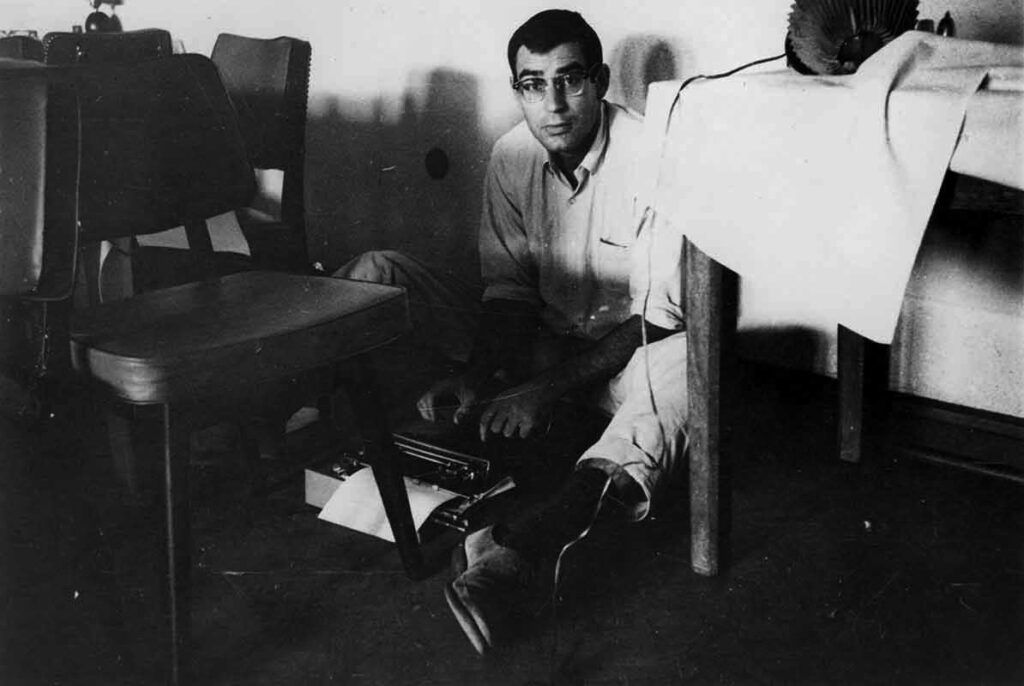

The actual physical jeopardy reporters were under. Halberstam had to pull a group of South Vietnamese secret police off of Arnett; they were beating him in the street. Sheehan was supposedly on an assassination list kept by Madame Nhu (sister-in-law to President Ngô Đình Diệm and wife of secret police head Ngô Đình Nhu).

It would have been very easy for any one of those reporters to simply disappear. Some of them were sleeping with guns next to their beds.

Later in the war, after reporting on the burning of Cam Ne for CBS News, Morley Safer heard from contacts that he needed to be careful where he went. Time magazine’s Wallace Terry reported on racial conflicts within combat units and was warned by black soldiers to watch out for white officers who might decide he wasn’t presenting a picture of unity and racial harmony.

Do you see any lessons for journalists today?

One constant is the importance of developing sources. In Vietnam, reporters went into the field and developed relationships with the soldiers and mid-level officers who were actually prosecuting the war. Sheehan’s book, “A Bright Shining Lie,” centers on Lt. Col. John Paul Vann. And Vann would talk to Sheehan because Sheehan was boots on the ground with him.

That’s what the best journalists still do. They do the digging and the footwork. The develop sources. They report the facts, give you context and tell you the truth.

How about readers and viewers? Do you see any lessons for the way we consume news?

Back then, you had three networks, the papers and wire services. Now it’s much more complicated. There has been a proliferation of outlets and platforms, as well as the rise of social media and extreme political divisiveness. We’ve got the Fox News brand of truth, the MSNBC brand of truth, etc. It’s all personality and conflict-driven as panels of experts debate the facts.

We have to be more discriminating about what we accept as fact. We have to ask: Who’s putting out a story and why? What gets leaked and what doesn’t? How reliable is the sourcing? Who’s controlling the narrative?

It’s such a Tower of Babel. You have to sort through information, disinformation and people asserting things that are blatantly false. But otherwise, the truth just gets lost.

“Dateline–Saigon” is now streaming on iTunes, Amazon Prime and other platforms. For more information, visit dateline-saigon.com.