When Jim McKelvey has a problem, good things happen.

Have you ever been to a café and paid for your food with your credit card on an iPad? Bought something from a street vendor and swiped your card through a little gizmo (called a magstripe) attached to a phone? Then you’ve used Square, a service that lets small-business owners easily accept credit and debit cards. It’s used by more than 2 million businesses around the globe.

It all started with a problem that McKelvey, BA ’87, BSCS ’87, had in 2009 when he was running his own small business, Third Degree Glass Factory, a studio for glassblowing and creating glass art in St. Louis. While trying to sell one of his signature glass bathroom faucets to a woman in Panama, McKelvey lost the sale because he couldn’t accept payment via her American Express card.

McKelvey called Jack Dorsey (of Twitter fame), with whom he had already agreed to start a new business, and explained how he had lost a substantial sale. “I was talking to my buddy Jack on this device,” he says, holding up his phone, “and I vented that it should be able to do anything that I would like it to do.”

McKelvey’s relationship with Dorsey had begun 20 years earlier when he hired Dorsey as a summer intern at Mira, a commercial document imaging systems company McKelvey founded with David Mitchell, another WashU engineer, in 1989. During his internship — and after Adobe Acrobat had begun dominating the imaging space — Dorsey helped McKelvey pivot Mira to a smart conferencing company, which is still a thriving business today. With Square, the two collaborated by first reviewing the limits of the existing technology and how it created havoc for small businesses. Then they set out together to create a mobile payment company as well as the prototype of the original hardware.

Today, Square doesn’t just help small-business owners accept credit card payments; it can help them do payroll, submit invoices, apply for loans and more through the Square app. The swiveling iPad register has become so ubiquitous as to be written up in the New York Times for how it’s changing the culture of tipping. (Vendors can choose to prompt customers to tip on the pay screen.) And innovations continue. In fall 2018, McKelvey and Dorsey announced the creation of a Square terminal, new technology aimed at replacing existing credit-card readers.

McKelvey … describes his days as time “spent on some problem that I consider significant and that remains a problem until we can figure out a way to solve it. And once it’s solved, I move on to the next problem.”

At heart, McKelvey is a problem solver. He describes his days as time “spent on some problem that I consider significant and that remains a problem until we can figure out a way to solve it. And once it’s solved, I move on to the next problem.”

The inclination to solve problems took root when he was a Washington University undergraduate. As a college freshman in the early ’80s, McKelvey took a computer-science course and found the textbook lacking. He subsequently — and on a dare — wrote a new textbook on programming. The publisher then approached him to write a second book, and McKelvey was a published author by his sophomore year.

McKelvey didn’t limit his focus to computer science, however. He had been an economics major before delving deeply into the engineering curriculum (eventually double-majoring in economics and computer science). During his senior year, as an outlet for artistic expression, he also studied glassblowing in the art school.

“These different schools [Arts & Sciences, engineering, art] had a profound effect on my life,” McKelvey says. “And although I consider myself an engineer, I couldn’t tell you which school was the most important for me.”

One result of his early achievement that proved very important, however, was an ability to join and often lead teams of the best and brightest. “One of the biggest lessons I’ve learned,” McKelvey says, “is that it’s always a team that gets something interesting done. The ability to work with people who are different from you — in many cases better and smarter than you — is absolutely critical. Those skills are precious.”

One result of his early achievement that proved very important, however, was an ability to join and often lead teams of the best and brightest.

And McKelvey continues to hone those skills, building great teams to carry on the daily operations of his varied enterprises. “I’m looking for complementary skill sets in operators, folks who are able to continue the day-to-day cadence of operations, which I’m not particularly good at,” McKelvey says. “I’ve been fortunate to have had some great partners who have that ability — working together and making things a little better every day.”

“Making things a little better every day” could be the mantra for another of McKelvey’s endeavors. When Square was first underway, it was headquartered in St. Louis. Yet Square’s need for high-tech workers outpaced the region’s capacity — unless Square had wanted to raid the high-tech talent from most other corporations in town. The company eventually had to move its headquarters to Silicon Valley to become fully operational.

Instead of moving on and leaving the problem of St. Louis’ lack of high-tech workers unaddressed, McKelvey thought about the problem and possible solutions on multiple fronts. How could he engage those wanting to learn computer programming, as well as the firms that could help train and eventually employ those newly trained?

In 2013, he partnered with Chris Sommers, Dan Lohman, Chris Oliver and others to form LaunchCode. A nonprofit, LaunchCode provides free coding courses for those seeking a technology career and helps companies find skilled workers for the growing number of tech jobs through apprenticeships, pairing inexperienced programmers with experienced mentors.

The nonprofit also started an all-female community coding group, CoderGirl, in 2014; and that same year, LaunchCode was named the “Best Thing to Happen to St. Louis” by the Riverfront Times. Today, LaunchCode operates in four hub cities and surrounding areas, and works with more than 500 companies. More than 80 percent of its apprentices, nearly 2,000 individuals, have been converted to permanent employment after an average of three months on the job.

And that’s what McKelvey likes most about being a serial entrepreneur: “It’s individual impact,” he says. “Meeting someone whose business was changed by Square or whose career was started by LaunchCode or who learned how to blow glass or learned from my textbook is the most important thing. I love that I’ve been able to have some impact on people, and my sincere hope is that it’s been positive.”

His latest business venture, Invisibly, has the potential to reshape the entire Internet. Right now, digital content creators and publishers continue to face daunting prospects for financial viability. Publishers typically convert just 2 percent of their audiences into all-access subscribers. Invisibly would work with publishers and advertisers to improve their ad technology, targeting only those users who have an interest in their products or services. Users would either agree to watch such targeted ads, building up credits by watching them, or make a micropayment through a digital wallet for content they’d like to access. The goal: to provide publishers with revenue for better content creation and to tailor users’ experiences according to what they actually want.

“I’m frequently afraid of some of the things that I try to do. … It’s like — Wow! How are we ever going to deal with this? And I hope that doesn’t show too often, but it’s there.”

— Jim McKelvey

The big question remains: Can Invisibly actually create the new revenue stream that publishers have been dreaming of and longing for to support the creation of better content? The quest across the industry has been akin to the search for the Holy Grail.

“I’m frequently afraid of some of the things that I try to do,” McKelvey says. “I get up, and I’m just freaked out by the magnitude of the problems that I’m working on. It’s like — Wow! How are we ever going to deal with this? And I hope that doesn’t show too often, but it’s there.”

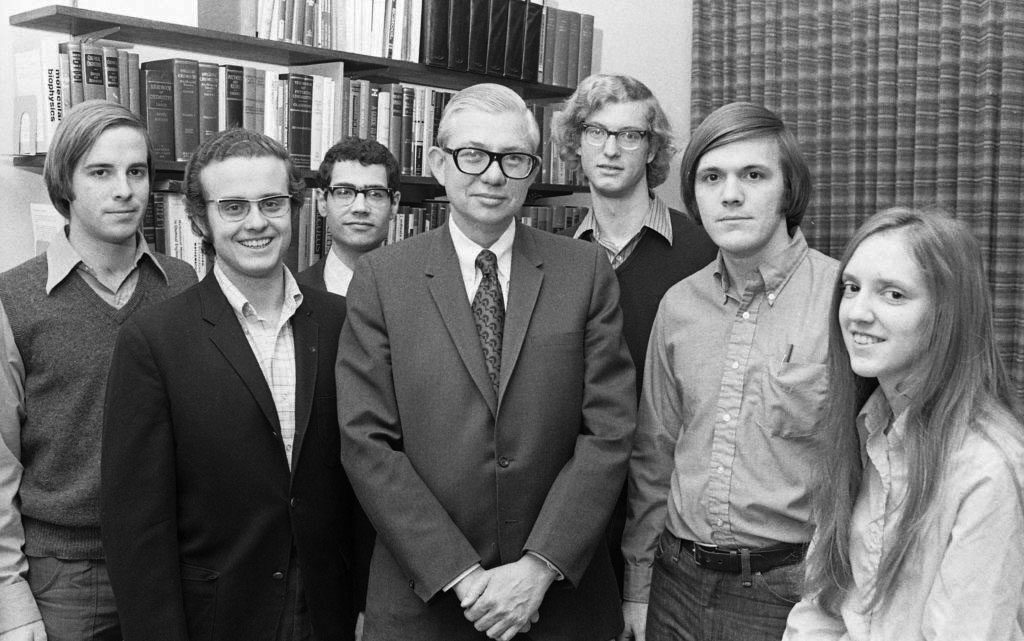

Asked if he ever turns to his father, James McKelvey Sr., MS ’47, PhD ’50 — who is credited with transforming Washington University engineering from a regional school to a nationally recognized research institution during his 27 years as dean — during times of uncertainty, McKelvey responds yes, but not in ways one would expect.

“My father is a living example of patience and humility,” McKelvey says. “It was not his advice; my father never turned to me and said, ‘Jimmy, if I were you, I would do x…’ Even when I ask for it, to this day he does not pontificate.

“But watching him, I would absorb the spirit of somebody who’s always been charitable and kind and modest, but also very accomplished. My father has been a great role model.”

Wanting to honor his father and his legacy and impact on the School of Engineering & Applied Science, McKelvey, in 2016, provided the lead gift for James M. McKelvey, Sr. Hall. When complete in 2020, the building will house the entire Department of Computer Science & Engineering. Situated just south of Preston M. Green Hall along Skinker Boulevard, it will also include faculty spaces and labs for each of the school’s five departments to promote collaboration.

“The engineering school was lackluster before my dad came on board,” McKelvey says. “He and Bill Danforth put the engineering school on the map. And it is wonderful to acknowledge his efforts with something that will stand at the front of campus and commemorate a man who gave his life to the university.”

Jim McKelvey and his wife, Anna, also recently gave an undisclosed naming gift to the engineering school, which has been renamed the James M. McKelvey School of Engineering in his honor. The gift will take innovation, technology and academics to new heights, building momentum by funding scholarships, professorships and the dean’s highest priorities for advancing the school and its impact on lives in the community and around the world.

With this transformative gift, McKelvey would like the university, and engineering in particular, to become a talent magnet and talent creator for St. Louis and the world. Further, he would like engineering students to be part of the collaborative teams working on and solving life’s big problems.

A quintessential problem solver himself, McKelvey says that if he could convey one thing to these students, it would be the following: “We are so strongly encouraged to be right that it puts a burden on us to deal with only the small problems that have already been solved,” McKelvey says. “To solve a big problem — one that hasn’t been solved — we must be willing to be wrong, and to be wrong many times over. And it’s not a desire to be wrong per se, but a willingness to be in that state for a while until one can finally emerge right.”