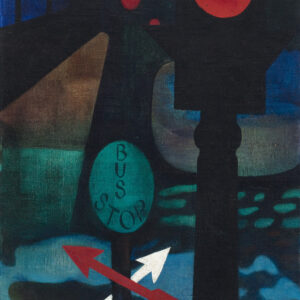

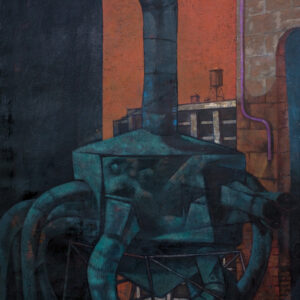

Water tanks pile high on urban rooftops. Chimneys sprout like trees in the forest. Rusting ventilators stride the skyline with theatrical flair and melancholy grace.

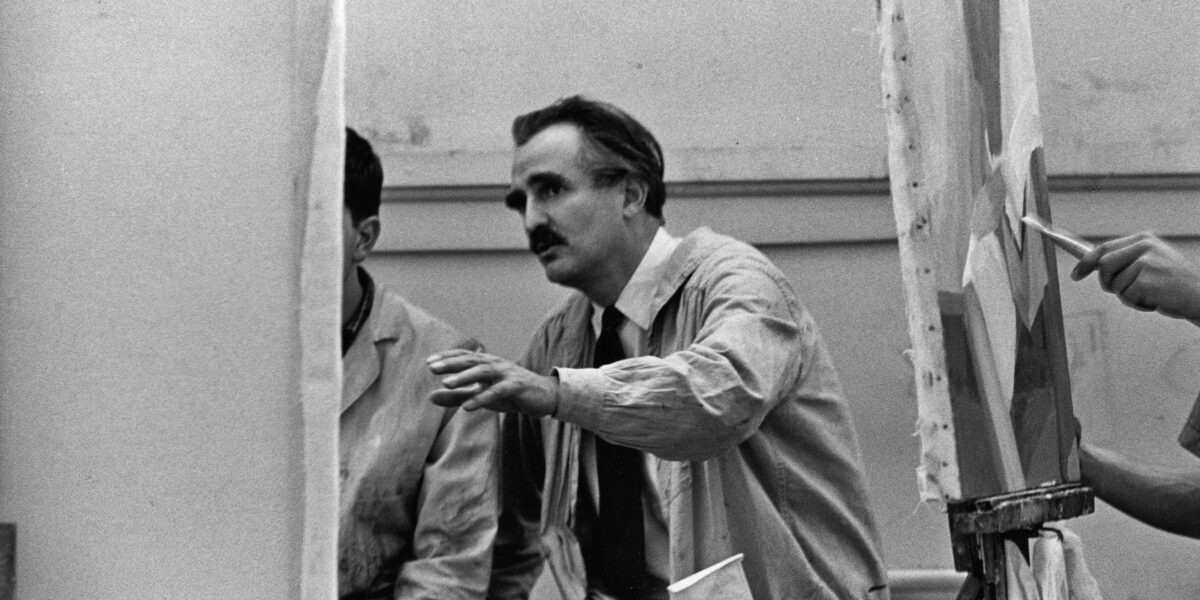

As a young artist in the 1940s, Arthur Osver won international acclaim for his evocative depictions of the American city. And though his work evolved dramatically over the next six decades — growing increasingly fluid and gestural — that ramshackle topography remained part of his painterly DNA.

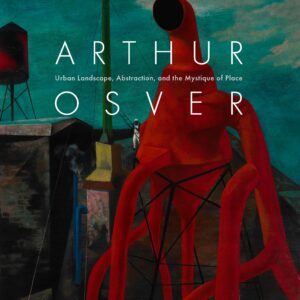

So argues Angela Miller, professor of art history & archaeology in Arts & Sciences, in “Arthur Osver: Urban Landscape, Abstraction, and the Mystique of Place” (2019).

Published by the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum, the book is the first to survey the whole of Osver’s practice, from his early career in Chicago and New York, through years abroad in France and Italy, to his long and influential tenure at Washington University in St. Louis.

“Osver remained tied to the world of buildings and urban landscapes, even at his most abstract,” Miller observes. Bridges, billboards, gas tanks, girders: “These raw materials of the industrial landscape became the instruments through which he expressed his own sense of place, his personal experience of the lived landscape.

“His paintings were not portraits of place but condensations of his impressions.”

A more innocent time

Born in Chicago in 1912, Osver briefly studied journalism at Northwestern University before transferring to the School of the Art Institute in 1931. There he met fellow painter Ernestine Betsberg, who would become his wife of nearly 70 years.

“When I got a fellowship to go to Europe, she said, ‘You stay there because I’m going to get one, too,’” Osver recalled in an interview with the Smithsonian Institution’s Archives of American Art. Sure enough, one year later, Betsberg joined him in Paris. The couple married in 1937 and spent months traveling and working in the south of France.

By 1940, Osver and Betsberg were living in a cold-water flat in New York’s Greenwich Village and later settled in Long Island City. Money was scarce, but their work — fueled by long, rambling bike rides — felt productive. Still, as time ticked past, Osver grew frustrated by the lack of critical feedback.

“It was just Arthur and Ernestine,” says Paul Shank, BFA ’64, a former student who now serves as co-executor of the couple’s estate. “Arthur revered her work but felt uncertain about his own. So he contacted the Museum of Modern Art. Could he bring something in?”

Astonishingly, the museum agreed. Osver met with director Alfred Barr. “That kind of thing just doesn’t happen anymore,” Shank says, shaking his head. “It was a more innocent time.”

MoMA purchased Osver’s “Melancholy of a Rooftop” (1942) and included it in the exhibition “Romantic Painting in America” (1943). A fuse was lit. Over the next decade-and-a-half, Osver’s work appeared in major surveys and one-person shows; graced the covers of ArtNews and Fortune magazines; and was acquired by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, the Saint Louis Art Museum and Washington University, among many others.

Places and things

With success came a nomadic lifestyle: teaching posts at the Brooklyn Museum, Columbia University, the University of Florida, The Cooper Union and Yale; a prestigious fellowship to the American Academy in Rome; exhibitions from Chattanooga to Tokyo.

By 1960, Osver and Betsberg “were getting older, and they’d never owned a house,” Shank says. “And Ken Hudson,” the Washington University dean of art, who’d previously recruited Max Beckmann and Osver’s friend Philip Guston, “was pretty dogged.”

Osver agreed to a one-year contract at the university. He stayed for two decades, and in many ways became the public face of the WashU painting program. (Betsberg also taught for a semester, before deciding that she disapproved of grades.) The couple bought a century-old home in Webster Groves. Ernestine painted in the living room; Arthur took the space above the garage.

“She’d make him lunch in the morning, he’d take it up, and they wouldn’t see each other again until evening,” Shank recalls with a smile. “They didn’t just wander into one another’s studios — not unless they were invited.”

For Osver, this newfound stability coincided with ambitious formal experimentation. Equally inspired and disconcerted by his time in Italy — with its ancient, light-filled cities, so different from urban America — Osver’s compositions grew brighter and more abstract. His brushwork became looser, his hues more saturated, his textures more varied. He painted in oils but also acrylics and even latex house paints.

Through it all, Osver retained a sense of architectural scale and structure. His “Pillar and Diagonal” paintings suggest classical building elements. The towering “Grand Palais” series recasts the famed Parisian hall as a grid on which to explore form, color and shape.

“There is mystique in places and things,” Osver observed in a 1968 exhibition catalog. “I once labeled myself essentially a landscapist. In a way I still am. Only, the landscape is becoming more and more an inner personal one.”

‘A great teacher and a generous man’

“A strong verticality runs through all of Arthur’s work,” says Philip Slein, MFA ’96, director of the Philip Slein Gallery. “You almost never see a horizontal painting.”

“There’s also a strong humanizing quality,” adds Slein, who recently organized “Arthur Osver: A Retrospective.” “But if you look closely, you can still see echoes of those early rooftops and industrial spaces. I don’t think they ever left him.”

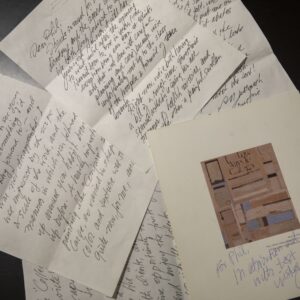

Slein, a St. Louis native, grew up with Osver’s paintings — in the form of exhibition invites local galleries sent to his parents — taped to the refrigerator door. As a graduate student in the mid-1990s, he decided to return the favor. Though Osver had retired more than a decade before, Slein sent him an invite to his own show at the University City Public Library. Weeks later, a hand-written critique arrived in the mail.

“It was just lovely,” Slein says with a laugh. “‘Dear Phil, I went to see your show. The red painting is looking pretty good, but you might want to reconsider the purple one…’ I never had a class with him, but it really meant a lot to me.”

Shank says that, throughout his life, Osver enjoyed keeping tabs on younger artists. “It’s not an easy field to be in,” Shank says. “Arthur wanted to be supportive. He felt it was his responsibility.”

Osver died in 2006, at the age of 93. Betsberg died the following year. In 2008, the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts established the Ernestine Betsberg and Arthur Osver Scholarships, which cover tuition in the College & Graduate School of Art.

“Arthur was a great artist and a painter of national significance,” Slein says. “His life was rich with artistic achievement. Even on his deathbed, he was trying to sneak watercolors into the hospital.

“But he was also a great teacher and a generous man,” Slein adds. “He shaped generations of artists. He was loved by his students, his colleagues and the St. Louis community.

“There was a yearning about his work, but I think he was fulfilled in his heart.”

“Arthur Osver: Urban Landscape, Abstraction, and the Mystique of Place” (2019) is published by the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum and distributed by University of Chicago Press. For more information, visit press.uchicago.edu.

“Arthur Osver: A Retrospective” remains on view at the Philip Slein Gallery through April 20. The gallery is located at 4735 McPherson Ave. For hours or more information, visit philipsleingallery.com.