Illustration once stood at the center of written communication, from Renaissance biblical texts to 19th-century daily newspapers, says Douglas B. Dowd. Now, thanks to 21st-century digital technology, illustration might just reassume a leading role and get its due as an art form.

“The tradition of the illustrator as a cultural reporter and interpreter is coming back because of things like the iPad and the movement of news to an electronic space — where you don’t have to pay to print illustrations,” says Dowd, an illustrator (http://dbdowd.com) and professor of art. In that first role, Dowd himself may be pointing the way for an illustration renaissance with the 2012 launch of his new magazine, Spartan Holiday. In it, Dowd, who publishes as D.B. Dowd, illustrates and comments upon his diverse travels, from the Utah desert to China and various points in between.

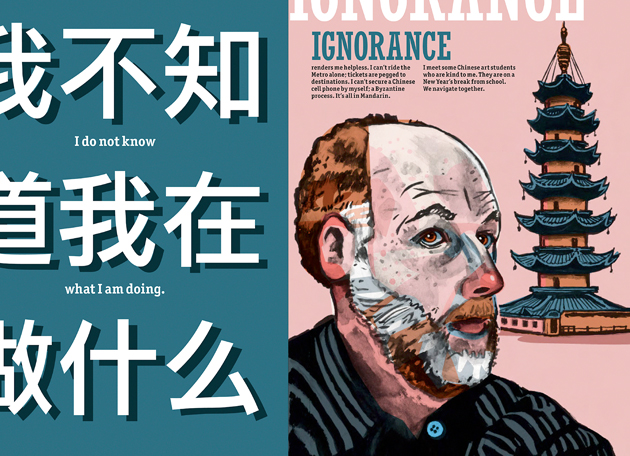

“In a most fundamental way, I’m engaged in visual journalism,” Dowd says. “A visual reporter who is drawing offers a different experience from a visual reporter who is using a camera. One is not truer than the other; the emphasis is just different.”

Yet Dowd argues for the primacy of illustration.

“I want to bring back re-engagement and the wonder of observation.”

—D.B. Dowd

“If I could wave a magic wand, I would make every educated person take a drawing class, because with drawing you have to look closely at structure.”

According to Dowd, society has been caught in a kind of echo chamber, where we accept received images and notions uncritically. “I want to bring back re-engagement and the wonder of observation,” he says.

As Dowd notes in his explanatory “Editorial Fixation” in Spartan Holiday’s inaugural issue, “Shanghai Pictorial”: “To celebrate a Spartan Holiday is to wring pleasure from modest stuff. To look and listen, to get a fix on things as they are. To embrace the vernacular. To enliven a rainy day. To gain independence from the media narrative of the week.”

A search for significance

Dowd, as curator, essayist and critic in modern graphic culture (including animation, comics and illustration), also strives to delineate and chronicle the role of illustration in modern history. He advises the Rockwell Center for American Visual Studies at the Norman Rockwell Museum in Stockbridge, Mass., which supports breakthrough scholarship in the preservation and interpretation of American illustration. In 2007–08, he co-curated with Stephanie Plunkett, Rockwell’s chief curator, the exhibit Ephemeral Beauty: Al Parker and the American Women’s Magazine, 1940–1960. The exhibit premiered at the Rockwell Museum, as well as the Mildred Lane Kemper Art Museum at Washington University.

“In Spartan Holiday, the interplay of words and pictures captures a true sense of his authentic experience, inspiring the reader to a more heightened awareness of our visual, sensory world.”

—Stephanie Plunkett

Plunkett frames Dowd’s work — both as an academic and artist — as a search for meaning. “The significance of published images throughout history and across cultures has been central to his academic research and his personal artwork for many years,” she says. “In Spartan Holiday, the interplay of words and pictures captures a true sense of his authentic experience, inspiring the reader to a more heightened awareness of our visual, sensory world. Life’s small moments, fully absorbed by the artist, are transformed from the mundane to the sublime.”

Yet that transformative power of illustration has not been fully recognized, Dowd says. He contends that illustration, with few exceptions, has been given short shrift in academia, a fact he seeks to alter. For one, he’s played a central role in building a major collection of American illustration at the university. The Modern Graphic History Library includes children’s literature, comics and pulps, periodical illustration, 19th- and 20th-century political illustration, and materials relating to graphic design and the history of printing.

Second, in writing about graphic culture, Dowd tries to sketch out some theoretical boundaries. “Illustration is a fairly under-theorized field,” he says, “generally falling outside the cultural narrative of ‘Art history’ with a capital ‘A.’”

That has occurred for a few reasons, he argues.

“Illustration and cartooning tend to be made by the middle class for the middle class. The most successful illustrators in the mid-20th century lived in places like Westport, Conn. Because they were not bohemian, they had a different cultural profile from ‘Artists.’ They were almost anonymous, as if the things they made were not made by people but by the culture,” Dowd says.

“I’m interested in who those people were and what it is they thought they were doing. I’m interested in the audiences they addressed and what those audiences thought about what they saw,” Dowd continues. “But in serious culture, these ‘artists’ don’t even exist.”

That’s due in great part, Dowd says, to art theory.

“The modern conception of the art object — a function of 18th-century aesthetics — is based on the fact that it is disinterested. That comes from Hume and Kant, especially,” Dowd says. “Those guys were interested in beauty, and the cultivation of taste.”

But functional objects and images — such as illustration — fell outside their interests. “Therefore, it kind of got in the water that art objects aren’t for anything,” Dowd says. “Art objects that are for something are in a completely different category.”

Creating His Niche

Despite his scholarly and curatorial work, Dowd’s focus these days is drawing. He sees himself as part of a tradition of cultural reporters extending back over two centuries.

“In the mid-1800s, for the first time, you could make a picture and print it fast and on a truly mass scale, in publications like Harper’s Weekly,” Dowd says. “Illustrators drew pictures, and then engravers turned these drawings into blocks that could be printed.”

“As an artist and a writer, I think of my subject as the social landscape of the culture that I live in. I’m working on projects that bring me into contact with an aspect of culture, which I try to describe and interpret.”

—D.B. Dowd

But with the advent of photography and technology to reproduce photos in print, the role of the illustrator diminished. However, a re-emergence came in the mid-20th century with the “visual essay,” as it was then called. “These illustrators worked for magazines, like Esquire or Sports Illustrated, that might send an illustrator on assignment, such as to the Rose Bowl,” he says.

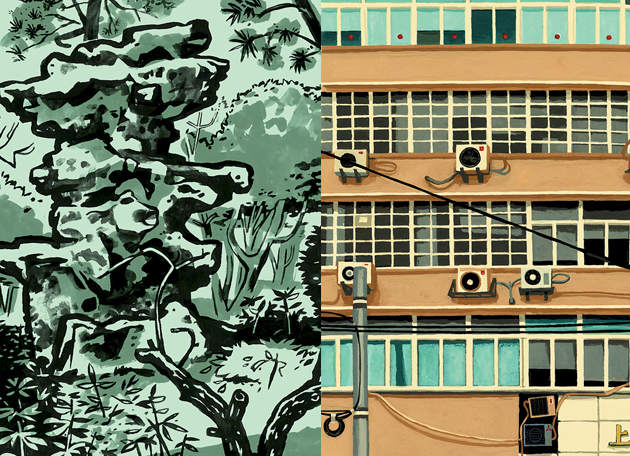

Likewise, Dowd sees himself chronicling his times. “As an artist and a writer, I think of my subject as the social landscape of the culture that I live in. I’m working on projects that bring me into contact with an aspect of culture, which I try to describe and interpret,” he says.

“I’m excited about Spartan Holiday because I feel as if I have finally figured out a way to integrate my desire to observe and comment upon contemporary life and the visual culture.”

But to arrive at this point on his creative arc took years. As an undergrad at Kenyon College, he eschewed painting, which “seemed kind of indulgent,” for history and drama. He next earned an MFA in printmaking at the University of Nebraska. He was doing well at making prints — which found their way into the collections of the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Walker Art Center, and the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C., among others. But he began questioning why he was making prints: “They take a long time to make, and they’re really expensive. So I [would] sell them to museums, where they [would] sit in drawers.”

Seeking more democratic art forms, he developed an illustrated serial “Sam the Dog,” which ran for two years (1997–99) in the St. Louis Post-Dispatch. In 2000, he launched an Internet animation venture based on “Sam the Dog” characters, which lives on at samthedog.com. That might have led to a television show, but Dowd had little enthusiasm for running the required production shop. He next moved into experimental animated films. And he worked as an editorial illustrator for publications such as the New York Times, Wall Street Journal and 0, The Oprah Magazine.

Dowd recognized that all his projects involved a mix of image-making, writing and social criticism, but also realized he had not yet arrived at the proper medium. “I couldn’t figure out how it all added up,” he says. And he wanted it to add up to something substantive and of social value.

“My dad is 82, a U.S. District Court judge in Ohio who still runs a courtroom. My uncle was a Presbyterian pastor and my mom a guidance counselor. A service ethic runs in my family; it was implicit that your work benefit someone else,” Dowd says. “I ended up in teaching, in some measure, as a result. But I also think it shows up in my work. I think of illustrators as people who are, by definition, contributors to a larger cultural tissue.”

Dowd’s latest project strives to do just that.

“I would love to publish Spartan Holiday for years,” he says. “And I’d like to be working on assignment at, say, a political convention as a visual reporter. That’s what I see my work as — and all I want to do now.”

Rick Skwiot is a freelance writer based in Key West, Fla.

Visit D.B. Dowd’s Faculty Portfolio page.