The nuns were popular. Too popular.

Fans clogged doorways; they blocked priests and delayed services. Sisters, in their superiors’ view, looked too much to the outside world and too little to church authorities. Something must be done.

And so, in the 1580s, Cardinal Gabriele Paleotti, archbishop of Bologna, launched a crackdown — on singing.

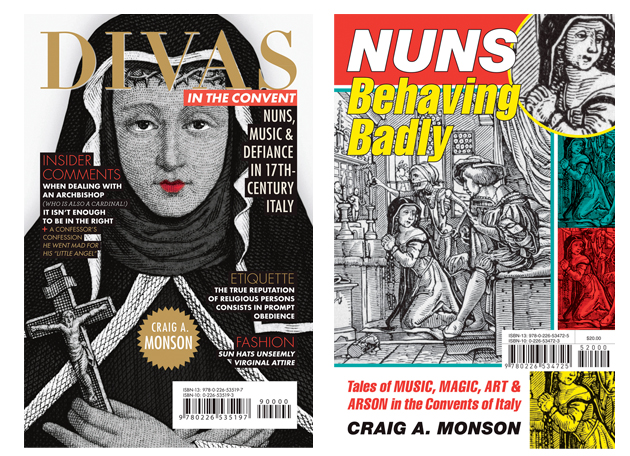

Thus relates WUSTL musicologist Craig Monson, PhD, in Nuns Behaving Badly: Tales of Music, Magic, Art & Arson in the Convents of Italy (2010). Sifting through the Vatican Secret Archives, Monson uncovers five remarkable stories that together reveal the history and traditions of Italian convent singing — and the challenges it posed for church officials.

The trouble began in the 1550s, as cloistered singers moved away from Gregorian chant and into the realm of polyphony, or choral singing in parts.

“What distinguished nuns’ choral singing,” Monson says, “was the character of the voices, particularly the highest voices. Sopranos, altos, tenors — all were women.” Lowest parts were taken by the bass viol or, when not outlawed, the trombone.

“When the nuns were in top form, theirs could be among the best sacred singing available,” adds Monson, the Paul Tietjens Professor of Music in Arts & Sciences. “No wonder convent choirs were soon among Italian cities’ top musical attractions.”

Moreover, for the aristocratic young women populating the most refined convents, such choirs “offered the only realistic opportunity for stardom that did not bear the stigma associated with public performance and the public stage.”

Church officials, however, remained suspicious. They feared that swelling crowds … “tempted the nuns to sing to the world and not to heaven.”

—Craig A. Monson, PhD

Church officials, however, remained suspicious. They feared that swelling crowds, listening through the grilled windows of the choir loft, “tempted the nuns to sing to the world and not to heaven.”

Singing was not the sisters’ only sin, to be sure. At the convent of San Lorenzo, Maestro Eliseo Capis da Venezia, master inquisitor of the Holy Office of the Inquisition, investigated allegations of folk magic, of casting beans and water divination, of baptized lodestones used to attract men. But music went to the heart of the matter. In the frenzy to locate a missing viola, one sister was said to have invoked the devil.

The master inquisitor collected testimonies (more than 100) and issued prohibitions, forbidding polyphony and instruments except the organ. In the aftermath, the nuns’ male superiors further commanded, with a hint of exasperation, and on pain of excommunication, that “nobody speak about the business of the viola.”

But Paleotti and others in the church hierarchy could not put an end to the business of cloistered transgression. Monson relates the story of Christina Cavazza, who slipped away from Santa Cristina della Fondazza to attend an opera. At Santa Maria degli Angeli, two young nuns, of suspicious intimacy, fled the convent hand-in-hand. The discontented sisters of San Niccolò di Strozzi burned their quarters down.

Nuns Behaving Badly builds on Monson’s Disembodied Voices: Music and Culture in an Early Modern Italian Convent (1995), the first book-length study of 16th- and 17th-century music and female monasticism. Earlier this year, he issued an abridged version for a less scholarly audience, Divas in the Convent, which details a tumultuous century at Santa Cristina.

Divas begins in 1598 with the arrival of 8-year-old Lucrezia Vizzana, a talented musician who would become Bologna’s only published convent composer. (In recent years, Vizzana’s strikingly modern motets have found renewed popularity on the concert stage.)

Working from original sources, Monson documents Vizzana’s training and formative years as well as the broader role of music in the life of the convent. He also documents the crises and disasters Vizzana’s music helped precipitate and Santa Cristina’s subsequent, long-running battle to regain a measure of independence.

“The history of the musical nuns of Bologna is thus a history of artists working against the odds, yet discovering ways to maneuver around barriers regularly erected by their diocesan superiors,” Monson says.

“It is a tale of these women’s attempts for most of a century to maintain some autonomy and some room to maneuver within an often-conflicting religious conformity imposed from the outside by the external, patriarchal Catholic hierarchy.

“To that hierarchy it became — and perhaps still is — a story of willful defiance.”

—Liam Otten is art news director for Public Affairs.

Editor’s note: Professor Monson will be serving as the faculty lecturer on an Alumni Association trip to Tuscany in June 2013. Visit Travel Programs for more information.