When Washington University moved from its downtown location to what is now the Danforth Campus in the early years of the 20th century, newly constructed buildings reflected a different time and place. McMillan Hall, for example — built as a women’s dormitory and completed in 1907 — was clearly of its time and place.

“When you look at the original plans for McMillan, you see the ironing room, linens room, sewing room, and servants’ or maids’ room,” says Jamie Kolker, assistant vice chancellor of campus planning and director of capital projects. Like the other buildings in the “pioneer group,” McMillan “supported a very different way of life.”

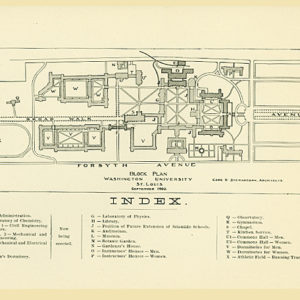

McMillan and the other original buildings exemplify the careful planning that went into developing the hilltop site the university purchased in 1894. The university employed the noted landscape architecture firm Olmsted, Olmsted, and Eliot to develop preliminary plans for the site. The firm recommended a monumental main building facing east toward Forest Park with a series of quadrangles stretching to the west.

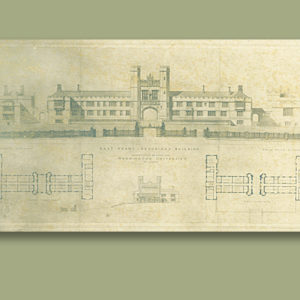

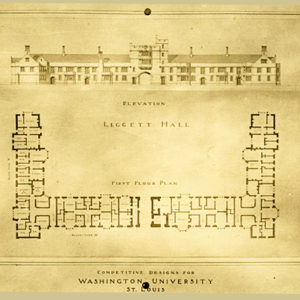

In an 1899 architectural competition, the university selected the Philadelphia firm Cope and Stewardson, whose block plan and elevations showed Collegiate Gothic-style buildings, cloistered quadrangles and flexible spaces. In 1901 the cornerstone was laid for Adolphus Busch Hall, designed to house chemistry labs — the first of 11 Cope and Stewardson buildings completed on the new campus.

Today, though, Busch — like McMillan — simply does not work for its original purpose. “The buildings are iconic,” says Henry S. “Hank” Webber, executive vice chancellor for administration. “They are the symbol of the university. In many ways they define this quite special place as one of the great campuses of America.”

The challenge, though, is that buildings such as Busch and McMillan were built for a bygone era. “These buildings were built 100 years ago,” Webber says. “How do we make them work for today?”

Transforming buildings for today’s use

While Busch Hall and others are no longer suitable for housing laboratories, Webber says these buildings can still work wonderfully as classrooms and office buildings. In 2008–09, Busch was transformed from an outdated academic hall into a modern home for several departments, such as history, in Arts & Sciences.

In recent years, the university has maintained more than 500,000 square feet of original Cope and Stewardson buildings and has followed an approach that invests in, preserves, restores, maintains and adaptively reuses the buildings in a variety of ways. Cupples II, renovated in 2011, provided eight new pooled classrooms and a home for the College of Arts & Sciences and the Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Portions of Brookings Hall have been carefully renovated and updated to reconfigure spaces and to improve lighting and mechanical systems.

But Umrath Hall was the “most dramatic of all” in transforming the interior spaces, Webber says. The particular challenge of Umrath, Webber continues, was because of its original use as a men’s dormitory. “The building had very small rooms,” he says. “Many of these buildings had this problem to some extent — very narrow corridors, then very small private spaces — but Umrath had it to a much greater extent, and the walls were load-bearing.”

The renovation, which called for removing the roof and taking out the load-bearing interior walls, was completed at about the cost of building a new building. Ultimately, the administration decided that renovation made more sense than replacement.

“While we care deeply about our history, about our iconic buildings, we are fundamentally a teaching, research and patient-care institution. We evaluate all of our decisions against whether we can make the building serve the mission of the university.”

—Hank Webber

“While we care deeply about our history, about our iconic buildings, we are fundamentally a teaching, research and patient-care institution,” Webber says. “We evaluate all of our decisions against whether we can make the building serve the mission of the university.”

One goal with Umrath was unifying its warrenlike passages and connecting its east and west sections over the arch. “It has fundamentally changed the way that building works and helps make it more flexible over time,” Kolker says. In fact, that upcycle strategy is baked into the design.

“The uses of that building will change; we know they will change. Any university building has to change,” he says.

The simplicity of the Cope and Stewardson buildings is what has made them so flexible, Kolker says. “Their brilliance is the fact that they have nice footprints — they’re not too deep, they have a lot of natural light, most of them have really big windows.”

By contrast, he says, buildings like now-replaced Mudd and Eliot were “so particular and so specific” that it was difficult to use them flexibly over time.

Webber points out that there are also technical aspects to making older buildings usable today: air conditioning, heating, lighting, access (both fire safety and disability access) and technology — all with an eye to keeping renovations within green building standards. Also important is opening up interior spaces for the way we work today, which, he says, is “much more collaborative, much more collective.” At the same time, preserving the wondrous details that were a product of the great craft of the era was key.

Looking Back, Looking Forward

Jamie Kolker believes that good campus planning means considering more than just the Cope and Stewardson historic buildings as university priorities evolve. He says, “I think the whole collection of buildings on campus has the potential to be thought of as representing a time and period. That’s a pretty broad definition of ‘historic.’”

Buildings may be considered “historic” not only because of the date of their construction but because of what has happened there (such as hosting the 1904 Olympics) or because of the role they play in the life of the university. Olin Library, Webber argues, is a building that “one would be very loathe to replace,” both because of its location and because of the essential role of a library at a university. Yet, the library is very different in its time period, architectural form and character than the buildings dating to 1900.

“We have to be respectful, certainly, of the past and learn from it, but we must also be a modern, forward-thinking institution that accommodates changes.”

—Jamie Kolker

A consideration, Kolker says, is that the university has to look forward to the next 110 years, just as it looks back 110 years. “We have to be respectful, certainly, of the past and learn from it, but we must also be a modern, forward-thinking institution that accommodates changes.”

As the university’s strategic Plan for Excellence unfolds, new, modern buildings continue to go up on the Danforth Campus, such as the Brauer and Green halls for the School of Engineering & Applied Science. For the Olin Business School, construction is under way on Bauer Hall and Knight Hall.

At the same time, the university will continue to invest in its historic buildings. The next Cope and Stewardson building to undergo extensive interior renovation will be Francis Gymnasium, as announced in October at the launch of Leading Together: The Campaign for Washington University. The project will include improvements to the existing Athletic Complex, an addition to the south side of Francis Gymnasium, and the renovation of the 36,000-square-foot gymnasium building into a state-of-the-art fitness center, to be named for benefactor Gary Sumers. Construction and renovations are expected to be completed in 2015.

The university’s approach to saving the buildings it can and finding creative ways to reuse them has worked well, Webber says. Indeed, campus planners are proud of what they’ve done to preserve the university’s historic buildings. But, he says, “we’re most proud that it provides a great environment for our students to learn and our faculty to teach and do research.”

Mary Ellen Benson is a freelance writer based in St. Louis and a former executive editor of this magazine.