Antarctica’s climate is the most hostile of any place on Earth, so why would anyone choose to go there to study the stars?

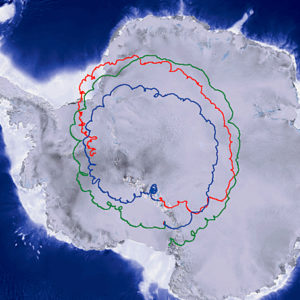

Improbable though it might seem, the frozen continent is an ideal observatory because a persistent current of air, called the polar vortex, circles the continent at high altitudes. A balloon launched into the vortex will make great leisurely circuits of the continent at the very edge of the atmosphere.

In fall 2012, NASA launched three balloon-borne astronomy experiments from Williams (or Willy) Field in Antarctica, but the star of the season was Super-TIGER, a two-ton detector the size of a billiard table designed by a consortium of institutions led by the university.

Ballooning sounds so sedate, so zen, but physicist and principal investigator Robert Binns, PhD, who has been part of 14 balloon missions, knew only too well that things could easily go wrong.

On one earlier mission, the squib that separates the parachute from the payload on landing failed, and the wind caught the parachute and dragged the payload 70 miles over the ice, straight toward the “Barrier” (edge of the Ross Ice Shelf) and the ocean.

On another mission, the balloon, instead of circling the continent, went off on a tangent and headed to the Southern Ocean. The flight was terminated over East Antarctica, in an area so remote that the scientists weren’t able to recover the instrument, which remains there today.

Hoping for 30 days aloft, Binns was ecstatic when Super-TIGER stayed up for 55 days, a record for heavy-lift scientific balloons.

But Super-TIGER launched on a nearly windless day, Dec. 9, 2012, rising majestically into brilliant blue skies, and then described nearly perfect circles over the continent — although it was mysteriously hung up for a nail-biting week over the mountains during its second circuit of the continent.

It didn’t make it back to Willy Field, but instead had to be brought down near a remote field station, when time ran out as it neared the Transantarctic Mountains. If it had been downed in the mountains, it would have been irretrievable.

Hoping for 30 days aloft, Binns was ecstatic when Super-TIGER stayed up for 55 days, a record for heavy-lift scientific balloons.

The longer the better, as far as Binns was concerned, because he was after not just your average cosmic ray but instead heavy ones, less than one in a million, which provide the best clues to the stellar origins of the cosmic rays.

Cosmic rays aren’t really rays but rather the naked cores of atoms cooked from lighter atoms in the bellies of giant stars and strewn across the galaxy when the stars explode — only to later coalesce into dust, asteroids, planets and people. Nearly every atom in our bodies was once a bit of dust like those that rained down on Super-TIGER during its majestic sky voyage.

We came out of Africa, it is true, but long before that, we came out of the stars.

Diana Lutz is senior science editor in Public Affairs.