In 2003, bestselling author Max Brooks published the Gray’s Anatomy of survival guides. The Zombie Survival Guide took readers on a journey through the anatomy of the living dead: their physical attributes, behavioral patterns and historical origins. Some balked at the concept, some wrote it off as nonsense, and some hid a copy under their bed just in case.

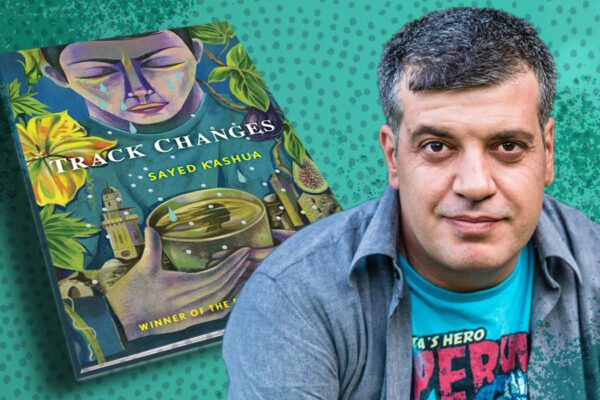

If you are Jamie Thomas, AB ’06, the survival guide sits alongside a collection of research on the re-animated dead: Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, Resident Evil, Night of the Living Dead, The Brain That Wouldn’t Die and soon, Zombies Speak Swahili, Thomas’ upcoming book published through Oxford University Press.

An assistant professor at Swarthmore College, Thomas specializes in sociolinguistics, Swahili and zombie studies. Given that zombies aren’t known to be literate or loquacious, the intersection of fields is both unorthodox and curious.

“Thinking about zombies is a way of thinking about what makes us human. That’s the way I approach it.”

— Jamie Thomas

“Thinking about zombies is a way of thinking about what makes us human. That’s the way I approach it,” Thomas, donning vibrant lavender glasses and a broad smile, explains. “And without language, humans are not as human as they purport to be.”

Thomas’ fluency in Swahili and love of language originated at WashU, where she studied Anthropology and Swahili Studies, but her zombie intrigue didn’t surface until her year of fieldwork in Mexico City, where she observed African studies classes. One day during a discussion around media and violence, a student introduced Thomas to Resident Evil, a survival horror video game with zombies speaking Swahili instead of their typical dribble.

Two years later, after traversing Tanzania and Micronesia, Thomas kept returning to that moment in Mexico City. Zombies, she thought, are the perfect medium for teaching why language matters to students.

“When you get this idea of a zombie being paired with a language like Swahili, what you begin to see is the dehumanization of such a language,” Thomas says. “Then it begins to point to a larger issue in the constellation of the way we treat each other – which languages count closer to humanity and which languages don’t.”

The conjuring of a zombie, which the American media appropriated from Afro-Caribbean culture, appeared in films like White Zombie and I Walked With A Zombie in the early half of the 20th century, but it wasn’t until George Romero’s 1968 B-movie Night of the Living Dead that we were introduced to the now-familiar creature: the peaked, wide-eyed, flesh-eating, once-human we know today.

Romero’s classic, which premiered at a time of extreme civil unrest, explores ideologies of otherness and enslavement. Ben, the black male protagonist and lone survivor after the attack, is “mistaken” as a zombie and killed by the same white mob that has come to save him.

According to Thomas, in using zombies to address racial tensions in the sixties, “Romero succeeded in igniting an imagination that also played to extant fears, to latent fears in the way our society works.”

Thomas’ undergraduate class, Languages of Fear, Racism and Zombies, delves into the evolving cultural iterations of the zombie and the present and prescient anxieties monster films communicate.

This year, the latest horror hit and talk of the town, Get Out, was a ripe case study. Jordan Peele released his horror thriller at a time when the Black Lives Matter Movement elicited a new national consciousness around race in America. Get Out follows Chris, a black man who visits his white girlfriend’s seemingly liberal family (“I voted for Obama!”) only to discover that his lover is not who she seems and his vigorous, youthful body will soon house the brain of an aging, blind, white man.

“What was particularly fascinating about Get Out is you get a full transformation now of the zombie to something that involves very expressly the brain, something that involves the subjugation of one’s consciousness and soul,” Thomas says. “It shows you how far the zombie concept has come in fifty years that you can basically have all the trappings of a zombie, but never mention the word zombie throughout the entire film, and people still get it.”

“Can we survive in more collective ways instead of fighting each other and killing each other?”

— Jamie Thomas

In Get Out, the evolution of the zombie mirrors that of racism — increasingly implicit and insidious, but ultimately as real and as threatening as ever before.

As the survivalist genre continues to adapt, Thomas has hope for the future of zombie films.

“I would like for some of these zombie narratives to challenge us more by presenting dystopic settings and contexts that force us to deal with more inclusive survival,” Thomas says. “Can we survive in more collective ways instead of fighting each other and killing each other?”

After returning home from an afternoon with Thomas, I receive an alert on my iPhone — George Romero, at 77, had died. Perhaps it was just a spooky coincidence, or perhaps it was a sign of the supernatural. Thomas hasn’t completely written off the existence of the occult, either.

“When I see a news story about somebody on bath salts eating someone’s face, that does fuel my curiosity.”