Segregation is no accident.

Nearly five decades after the Fair Housing Act of 1968, American cities remain racially, culturally, spatially and economically divided. Entrenched conditions and persistent biases undermine the policies and priorities that would heal lingering wounds.

So argues Catalina Freixas, assistant professor of architecture in the Sam Fox School of Design & Visual Arts. Last semester, Freixas and Mark Abbott, professor of history and director of the Center for Neighborhood Development at Harris-Stowe State University, launched “Segregation by Design.” Developed as part of The Divided City initiative, their class — which will be offered again next fall — explores both the historic roots and present-day reality of urban separation.

In this Q&A, Freixas discusses St. Louis, segregation and the hidden histories that shape our urban landscape.

You’re from Argentina but joined the Sam Fox School faculty in 2004. What drew you to the topic of American segregation?

My research is about vacancy, sustainability and resiliency. I was interested in the condition of vacancy in St. Louis. Land is an asset. Building stock is an asset. But somehow, in post-industrial “metamorphic cities,” vacant land and vacant buildings are seen as deficiencies. I wanted to understand why — and specifically how race and segregation contribute to that.

I also wanted to show that architecture is about more than buildings — that architecture has a social agenda. The environment we see around us is the consequence of specific design and planning decisions. Once students understand how things went wrong, they can also understand how things can be improved.

If you don’t talk about the problems, you cannot find the solution.

Can you give some examples of how segregation policy shaped the city?

The condition is systemic. Redlining shaped housing patterns and racial distribution. It shaped which neighborhoods would be eligible for mortgages and loans, which would be destroyed by highway infrastructure, and who would be displaced. It shaped our approach to transportation and public services.

These decisions were not random. They were designed. And the effects are everywhere.

You mention redlining. How did that work in St. Louis? And how does that history manifest today?

Even before redlining, St. Louis attempted to legislate where whites and blacks could live. When that was ruled unconstitutional, the city tried to accomplish the same objective by coercing property owners into signing restrictive covenants.

When that was ruled unconstitutional, residential divides were delineated through federal housing policies and local zoning practices. FHA loans were denied to inner-city African-American neighborhoods. Public and subsidized housing were clustered close to the downtown and north of Delmar. And suburban ordinances inhibited African-Americans from moving into new communities.

These patterns remain. When you look at a map of St. Louis, you can see that the redlined neighborhoods still have the highest vacancy and poverty levels. People in these communities still don’t have access to mortgages, services and essential amenities. This devastation was intentionally created and perpetuated.

Your students also examined the disappearance of historic African-American communities from central St. Louis County.

Meacham Park is an African-American community located between Big Bend Boulevard, South Kirkwood Road and Highway 44. Until the 1970s, it didn’t have sewage systems and other basic infrastructure. But in the 1980s, there was a terrible fire and residents voted to incorporate with Kirkwood. They wanted the same services as other St. Louis suburbanites.

But Kirkwood developed all the commercial property into big-box stores, which in essence destroyed the neighborhood. Residents were promised employment opportunities, but were effectively blocked from Kirkwood Commons. Today, Meacham Park is completely isolated; it has only one entrance and exit. It has lost housing stock, population and jobs. Proposed land-use maps show it as an industrial zone.

Something similar happened in Brentwood. An African- American neighborhood, taken through eminent domain, was developed into a big-box complex. Gregory Carr, an instructor at Harris-Stowe, grew up there. Where his home used to be is today the grocery section of a Target.

You’re compiling a “Segregation by Design” book, which will feature conversations with Carr and other guest lecturers from the worlds of policy, design and the humanities. But the class also developed mitigation proposals. How did things proceed, day-to-day?

To begin, students selected one of six communities, conducted background research and analyzed the community’s historical evolution. Then they started walking. They documented the neighborhood’s physical makeup — the state of its housing, landscape and infrastructure — as well as the age, race and activities of the residents they encountered.

Next, students learned about research techniques and sources. They interviewed community members and studied best practices. Their end products were neighborhood plans outlining a variety of policy and design strategies.

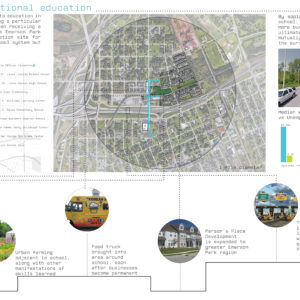

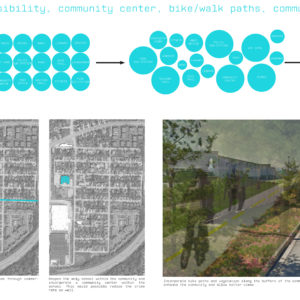

In addition to Meacham Park, students worked with professional mentors to develop plans for the city’s Central West End, Tower Grove South and West End neighborhoods, as well as for City Center in Florissant and Emerson Park in East St. Louis. Can you give examples of specific issues or conditions they addressed?

City Center was developed as a post-war working-class community. But as homeowners pass away or move into retirement communities, properties fall into the hands of absentee landlords or become vacant. To attract younger residents, our team proposed a denser, more active commercial district along St. Francois Street, the community’s main corridor, as well as strategies that would allow seniors to “age in place” while increasing home ownership among current renters.

The once-prosperous West End, located between Delmar and Page, experienced a very traumatic racial transition in the 1950s and ’60s. Though recent years have brought an influx of affluent whites, the West End still suffers from high rates of poverty, chronic disease and crime. The challenge confronting our team was to develop a mitigation plan that would maintain revitalization momentum without leading to gentrification and displacement.

The Central West End team proposed a Special Business District to span the city’s infamous “Delmar Divide.” But while researching, the group discovered that many area deeds still contain restrictive covenants. That’s a little shocking.

In Shelley v. Kraemer, the Supreme Court made deed restrictions unenforceable — it did not scrub them away. Unless property owners removed them, at their own initiative and expense, the restrictions are still there. In many cases, they’re attached to properties that are now owned by African-Americans. It’s very insulting, but it’s not just the Central West End. A lot of neighborhoods still have them.

I actually live in the Central West End. I want those covenants out of our deeds.

That really underscores the persistence of history. Looking forward, do you see cause for optimism?

These are tough topics, and some of the class conversations were not easy. For example, we discussed Ta-Nehisi Coates’ “The Case for Reparations,” and his contention that America needs to reconcile not the sins of the past, but the sins of the present. It made students of all races uncomfortable.

But I’ve never seen students so engaged. And we should always have hope. Policy and design can effect change, and I’m very optimistic about this new generation. They want equity. They want a more diverse society.

Many students joined the class because they had personal experience with segregation or had seen what gentrification has done to their hometown communities. Now, they felt they had an opportunity to learn, to speak up and to say something.