Janice Mirikitani is a survivor. As a child during World War II, she was “forcibly relocated” with her family to a Japanese-American internment camp. As a teen, she suffered abuse at the hands of a family member. As an adult, she channeled her life experience into a remarkable career as a poet, dancer, activist and educator. Since 1965 she and her husband, Rev. Cecil Williams, have led the Glide Memorial Church, which provides extensive social services to marginalized communities in San Francisco.

Mirikitani will present the keynote address at the universitywide Day of Discovery & Dialogue, to be held Wednesday and Thursday, Feb. 22 and 23, at Washington University in St. Louis. Her presentation, titled “Giving Power to Voices Endangered by Silence,” will take place Wednesday at 5 p.m. in the Eric P. Newman Education Center on the Medical Campus. The event is open to members of the Washington University community and advance registration is requested.

To inspire thought within our community ahead of her talk, here Mirikitani offers a few insights into how we think about identity and class, and what we can learn from each other.

Your experience has given you an incredibly powerful perspective on identity. How are we each shaped by our own personal experiences and what can we learn about ourselves by learning about others?

It’s very complex. Issues of diversity, inclusivity, acceptance, communication and creating relationships meaningfully are very complex. I have been astonished by so many people. In fact, the people who are out there needing help, in the lines out on the sidewalk, are my greatest messengers. They’re the ones who teach me every day I need to keep my mind, my heart, my thinking open all the time for new ways to be educated. When I share my story with them, tell them I’ve been a battered woman, I’ve been addicted to too much drinking, I share all my truths with them. And they say, “But you’re the minister’s wife and you’re a teacher and you got a college education…” and I say, “I’m the same as you. I have the same wounds you have.” And I think that connects people more than you realize. Our wounds connect us more than the way we look or dress.

When we talk about diversity and inclusion, our focus often tends to be on race. Is it important to broaden the conversation to also include class and other considerations?

I think we’re too segmented as individuals. The issues of class, race, gender, sexual orientation, immigration status, economic status — all of these different situations are connected and they make us a total human being. There are many factors that go beyond the categories that we’re choosing to classify or box ourselves into, and I think we need to acknowledge that box, look at it, describe it, and then figure out what it will take to climb out of it so we can begin to see the connections we truly do have.

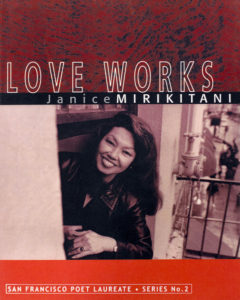

In the poem “Yes, We Are Not Invisible” from your book “Love Works,” you talk about the types of stereotypes that frequently attempt to define groups of people. How is this harmful, and what can we learn from a deeper examination of these words, thoughts and behaviors?

In the poem “Yes, We Are Not Invisible” from your book “Love Works,” you talk about the types of stereotypes that frequently attempt to define groups of people. How is this harmful, and what can we learn from a deeper examination of these words, thoughts and behaviors?

Stereotypes dehumanize people. They cause us to continue to distance ourselves and see other people as “less than.” Stereotypes are perpetuated by media, by each other, in our schools — we do not have enough curriculum in public schools and universities to teach culture and educate people about different ethnicities, lifestyles and human conditions. I can’t begin to tell you the types of stereotypes I hear because I’m Asian American. People presume I’m great at math, or that because my husband is African American, he must be my chauffeur or I must be a caterer or florist. I’m a poet laureate and people ask me where I learned to speak English so well, assuming that because I’m Asian I must be an immigrant. It is dehumanizing and demeaning, and makes us a smaller people. But what it really does is it diminishes the person who holds the stereotype. If I know who I am, it doesn’t diminish me, but it’s an insult. It hurts me. And it’s my responsibility to say that’s a very negative stereotype and I take offense to it; let me make a correction.

You write about the power of the word to “awaken our passion for justice.” Why is this so important, especially today?

This is more important now than ever. If Donald Trump has done anything to help us, it’s to wake us up a little bit. I’m not condemning or criticizing his supporters, but I do believe we took our eyes off the country. We did not look deeply enough into those who did not feel heard. People basically didn’t care about the people who live in the rural areas, the working class, blue collar workers, people whose jobs have been taken away to overseas. We’ve taken our eyes off of that group of people who felt unheard, angry, hateful toward immigrants. They saw there was this guy who had enough guts to say what they really felt. There are many ways in which our passions should be awakened. I can’t speak for you. I hope you will think about what this means for you and your community — even if it’s not your community that is being directly affected.

Universities by nature are places of great diversity of people, thought and opinion. How can a community like ours contribute positively to the national and global conversation about diversity and inclusion?

First you have to be willing to be honest with yourself. Lying to yourself is the first thing to overcome. There are people who are lying to themselves and saying they’re not a racist, but when you look at their circle of friends and there is not one person of color, you have to ask what that means. If you’re working only with people who are just like you — similar backgrounds and skills — I would ask you, how would you break out of that? In terms of the human experience and the relational experience, I believe diversity is the only way you really can see your true self. The only way you can get to the full dimension of yourself is through living with diversity, living in it, and not through tokenism. Authenticity is at the bottom of it all. You have to be who you really are.